Ideal Syllabus: Eileen Myles

The artist discusses the books that have influenced her

The artist discusses the books that have influenced her

I woke up at 4am and got a reminder email from frieze that I said I would do this, and I wrote back ‘tomorrow’, but it is tomorrow, so okay:

CA Conrad, The Book of Frank (2009)

If you take a poor queer kid and drop him in the language-centric poetry world of Philadelphia in the 1980s, and all he’s read up until then is Anne Sexton poems and Joni Mitchell lyrics, and you further expose him to haiku and the history of surrealism, and then someone else tells him that each of those things is wrong, but he’s in therapy and he’s got to make a compatible place in his own writing for the spiritual realignment and emotional recovery he’s going through, this book is the result. I think it’s one of the best books of poetry that will be published this century, honestly. (Full disclosure: I wrote the afterword.) It’s dark, and mean, and sweet, and concise, and pop, and dirty and apocalyptic. Whoever you are, it’s everything you like.

Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita (1966)

The reader travels desperately from a park in Moscow to a mental hospital, probably also in Moscow, to the interiority of Pontius Pilate, who knows in his heart he should save this man, to a hotel room full of Soviet apparatchiks and a large black floating cat. Bulgakov’s hallucinatory testament to imagination and political desperation and personal deprivation is one of the glories of world literature and defies categorization, though it surely is a novel.

Maggie Nelson, Jane: A Murder (2005)

I think everyone should read The Argonauts (2015), and many of you will have, and, of course, you should read Bluets (2009) but, if you want to see when and how Maggie Nelson became Maggie Nelson, read this novel in verse. It takes up the incident of her 23-year-old aunt Jane’s violent death, which was the result of trying to get home via a free ride advertised on an index card posted to a board at her college in Michigan sometime in the 1960s. To have such a heartbreaking event occur in one’s family creates a system that holds fact and sorrow, and a younger Nelson sifts through her aunt’s notebooks and poems, and interviews people like the boyfriend she was about to marry. It’s a portrait of a life frozen and a life haunted, and a meeting between generations of women and the birth of a writer. It’s a perfect book and one you won’t forget.

Christopher Isherwood, Down There on a Visit (1962)

This novel in four parts taught me that a book is a house that has rooms which the soul of the writer can travel through to tell himself different things by appearing in another room, in another way, at a slightly different time, towards a single purpose, I think, though, of course, it is always unnamed. Maybe finding God through other men?

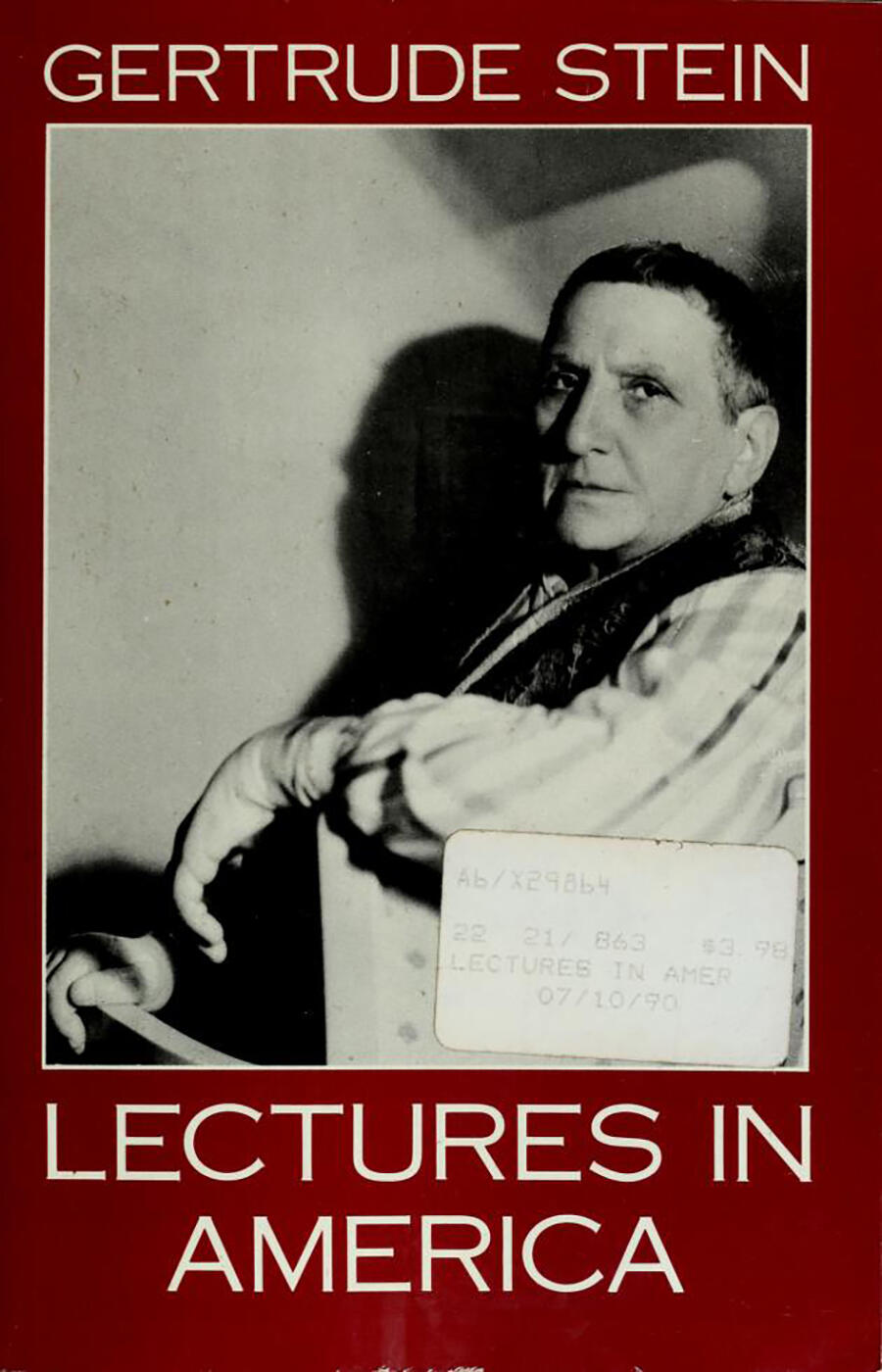

Gertrude Stein, Lectures in America (1935)

Let’s face it, writers used to make their living going all over the world giving actual talks. I think of Charles Dickens doing this, I think of Oscar Wilde and I think of this book, which is the perfect voiceprint of a female author pedestalizing her own genius and pulling it off. She had earned this spot, having written for years and been mocked by us journalists for her silly repetitious writing, and mocked by editors, too, in their rejection slips. It’s uncanny and American, I think – Warholesque even (though he’s the copy) – that Stein, by figuring out how to write about her own self in more conventional prose in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), would produce a more successful other who could then perform her actual self and perform literature for us, which she does in this book. Her talk ‘Portraits and Repetition’, included here, is my bible.

Gwendolyn Brooks, Maud Martha (1953)

A perfect act of vulnerability, architecture and form, Gwendolyn Brooks’s novel shows the inside of relationships and cohabitation in prose that is almost pure quotation (in feeling), except that every line functions to establish the time and the world her main characters and her various friends and lovers are living in. This is a dream of a book.

Halldór Laxness, Under the Glacier (1968)

Halldór Laxness, Iceland’s only Nobel Prize winner, bought a Jaguar and, for as long as he lived, people said he drove down the same road every day, fast as hell, and then he went home and wrote. Or maybe he wrote and then he drove. I love all of Laxness’s books, but especially this one, which is an imaginative transcription of the journey of a young church minister set with the task of going out to the west of Iceland to see the funny goings-on and compile a report. I think Laxness explains the Icelandic character through this book. Having been a world-class author, who went to Hollywood and hung out with Bertolt Brecht, he nonetheless went home and kept writing, using the scale of his experience to invest the lime-green and grey landscape of the west of Iceland with all the magic of the world, freshly located now in a melting glacier and a non-native cult, seemingly flourishing.

Fred Moten, The Feel Trio (2014)

In three movements, poet, scholar and thinker-on-the-hoof Fred Moten incants and deliberates his own quivering, emotive, analytical, greedy, joyous condition in language. If you wonder why you like poetry so much, this wide slim volume is one explanation.

Violette Leduc, La bâtarde (1964)

It’s such a big book. It starts with the simple female fact of hating your mother and then travels through sex and ambition, and self-love and self-loathing, in a prose that’s always reaching into poetry, squeezing and going forward in a startling, tentative way so intimate that it has so much time to think about itself. Never boring, always ripe, this is one of the most generative books I’ve ever read.

Can Xue, Dialogues in Paradise (1989)

No other book has explained so perfectly to me how suffering creates surrealism, how starvation makes art, how storytelling is a medicine to survive and bear drastic intervals of time that seem impossible to weather and do with so little. This is a large and smiling book, which is a muscular state of mind filled with horror and delight. Can is one of the great writers of the world and this book, which is simply tales and an intro, brings you to her kitchen-table workshop and solders all the stories together in history and magical embodiment. She’s a once and future master.

Djuna Barnes, Nightwood (1936)

This perfect, perfect novel is like a dark echoey growth. All the parts get all over each other. It’s such a compressed and drunken book: drunk on passion, and the horror and inescapable, hapless and wreathy condition of female lust.

James Schuyler, Collected Poems (1993)

Then read this.

Main image: CA Conrad, The Book of Frank, 2009, book cover