Ideal Syllabus: Alexander Chee

With his new book How to Write an Autobiographical Novel published today, the writer shares the books that have influenced him

With his new book How to Write an Autobiographical Novel published today, the writer shares the books that have influenced him

Joan Didion, Play It as It Lays (1970, Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

From the first line – ‘What makes Iago evil? Some people ask. I never ask.’ – there’s a wonderful snarl to this novel that I loved right away, a seam of anger that you trace to the end. Didion is always tricky to bring up, as she’s been so many kinds of writer by now that it is hard to know which Didion you are discussing. I myself love middle-to-late-period Didion, but this book is from her youth – the one she tried to annihilate during her middle-to-late period – and features a former starlet in Los Angeles who is on the slide, rocked by grief and betrayal, and determined to take at least a few people with her. Reading it, I was one of them. All these years later, I still feel a little bit like I am.

Natalia Ginzburg, The Little Virtues (1962, Arcade Publishing)

Each one of the essays in this slender volume strikes with a quiet percussive force – by which I mean, I think you read this book and fall in love with its writer. Ginzburg was a giant of 20th-century, Italian postwar literature – or, at least, she’s my giant of this time – and I loved every one of these texts. Part of their power, for me, derives from the acknowledgements, in which she says she can’t make corrections to the essays meaningfully because of the time that has passed. She dedicates the book to someone who is not present in the essays but is ‘the person to whom most of them are secretly addressed’.

Christa Wolf, Cassandra (1983, Farrar Straus and Giroux)

This was not my first Christa Wolf novel, nor was it my last, but Cassandra, and the attached essays on the poetics of writing it, taught me new possibilities of many kinds. I learned that novels could have poetics; that there was room in a single book for writing fiction and nonfiction in relationship to each other; that documenting one’s artistic process and treating fiction writing as both a methodological and mysterious practice had value. It also taught me how to write historical fiction out of myth, and to do so in ways that spoke to the present without being didactic or fraught.

Janet Malcolm, The Silent Woman (1994, Granta)

I first read this in serial form in The New Yorker. I loved it but I didn’t understand exactly what had been done. The second time, it was a book and I understood better what had been done; I loved it in a new way, even as I learned something about reporting, literary journalism and structure. A very short synopsis would be that Janet Malcolm reads the extant biographies of Sylvia Plath, identifies what each one of them failed at, and then pursues what she deems the ‘get’ each author missed – and gets it. It would almost be vindictive, if it weren’t in the service of some greater truths about literary biography, celebrity and the problems inherent in writing about a deceased famous writer when their spouse is still alive and may not want the story told.

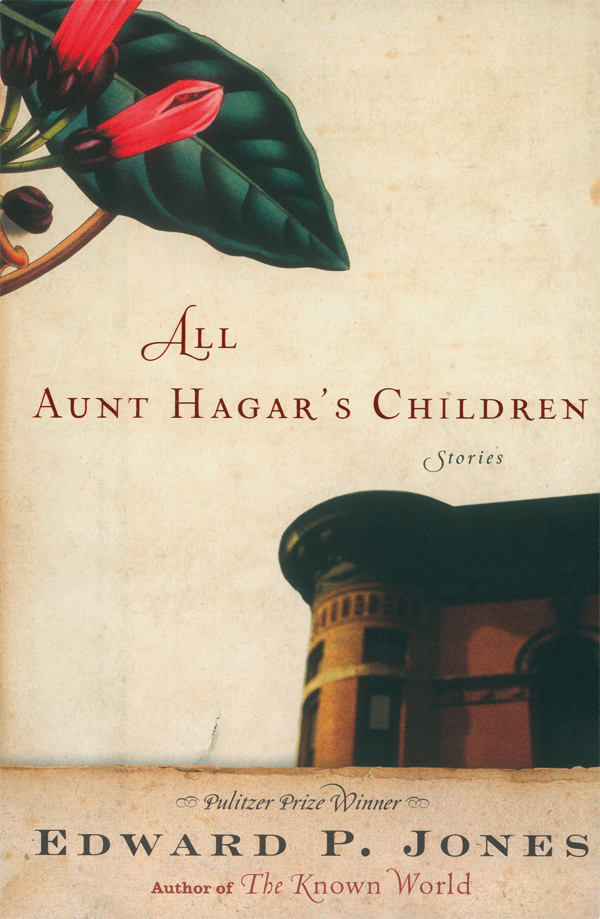

Edward P. Jones, All Aunt Hagar’s Children (2006, Amistad)

There’s a rich intimacy to these stories that makes them possible. In some ways, Jones seems to know these characters like God would, but his intimacy with them is so human because he seems to love them, too – not for their virtues but for their humanity. My favourite is probably ‘A Rich Man’, which begins with a character who dies almost immediately then takes us into the foolishness of her widower, who is determined to enjoy his freedom from his wife. Jones brings us through a host of characters, all the way to the story’s devastating and wonderful ending. The collection as a whole is like a picaresque novel – if the form could comprise many different people instead of only one – and achieves this by making a trip through black life in and around Washington, D.C., which no one else could provide.

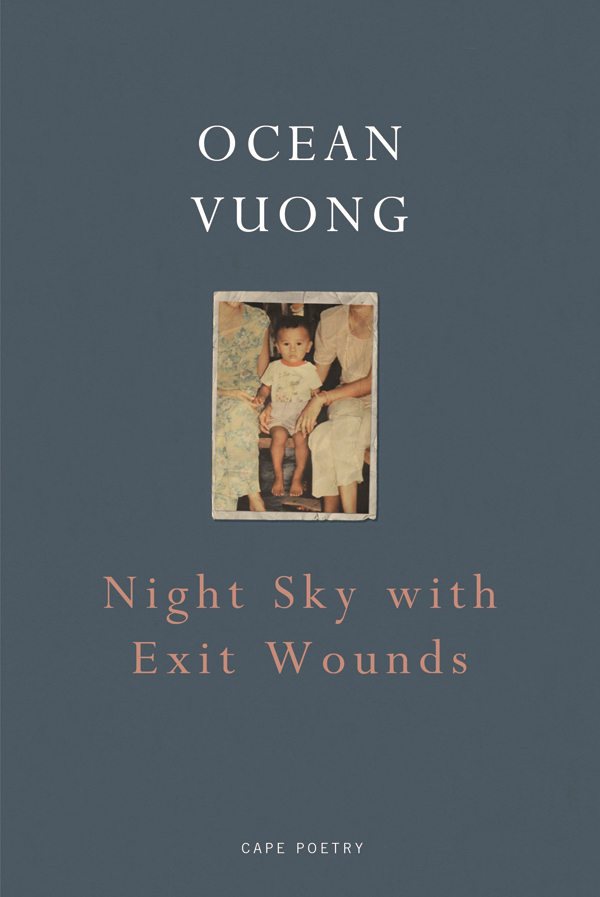

Ocean Vuong, Night Sky with Exit Wounds (2016, Jonathan Cape)

Sometimes, I think of it as a song cycle; sometimes, a book of poems; sometimes, an epic. Vuong puts himself at the centre of this collection in an astonishing way, even as he is also entirely willing to set himself aside. The result is an expansive nature in the poems, which is the author’s way of reconciling his queerness with the lost language of his mother and grandmother and the stories they wouldn’t want to know, or wouldn’t tell, about the Vietnam War, the US, him, his father. ‘Maybe the tongue is also a key,’ he writes. And I thought, ‘Yes. Yes.’ And then turned the key.

David Wojnarowicz, James Romberger and Marguerite Van Cook, 7 Miles a Second (1996, Fantagraphics Books)

Wojnarowicz is one of my favourite writers, and I love his 1991 book Close to the Knives dearly, but this was his graphic novel, planned with his friends James Romberger and Marguerite Van Cook, who completed the book after his death. It first appeared as a comic book from DC – maybe the best thing they’ve ever done – and is now available in a beautiful, large-format publication that lets the art sing. The story is of his last days, as he is dying of AIDS, and we go with him on journeys back through his life, from his time as a hustler and a junkie in Times Square to a hallucinatory present. The title refers to the speed needed to leave the Earth’s gravitational pull behind, which to my mind is exactly the speed you feel as you read it, though you are drawn not above the Earth but more deeply into it, into the lives of those of us left behind.

Main image: Joan Didion, Play It as It Lays, 1970, book cover. Courtesy: Farrar, Straus and Giroux