Imaginary Soundtracks

Revisiting the Penguin Café Orchestra

Revisiting the Penguin Café Orchestra

Of all the descriptions of the Penguin Café Orchestra I’ve come across – ‘modern semi-acoustic chamber music’ and ‘imaginary folklore’ being two of the duller examples – my favourite has to be ‘the soundtrack to a macrobiotic dinner party in Winchester in 1979’, as coined by blogger ‘stevie t’ some years ago. Listening to this summer’s carefully remastered reissues of their first six albums – Music from the Penguin Café (1976), Penguin Café Orchestra (1981), Broadcasting from Home (1984), Signs of Life (1987), When in Rome (1989) and Union Café (1993) – I find myself thinking not of kora players in Senegal or a folk session in an Irish pub, as some of their more demonstratively cosmopolitan musical confections strove to evoke, but of certain post-1960s English archetypes.

Penguin Café Orchestra, ‘Perpetuum Mobile’ (live)

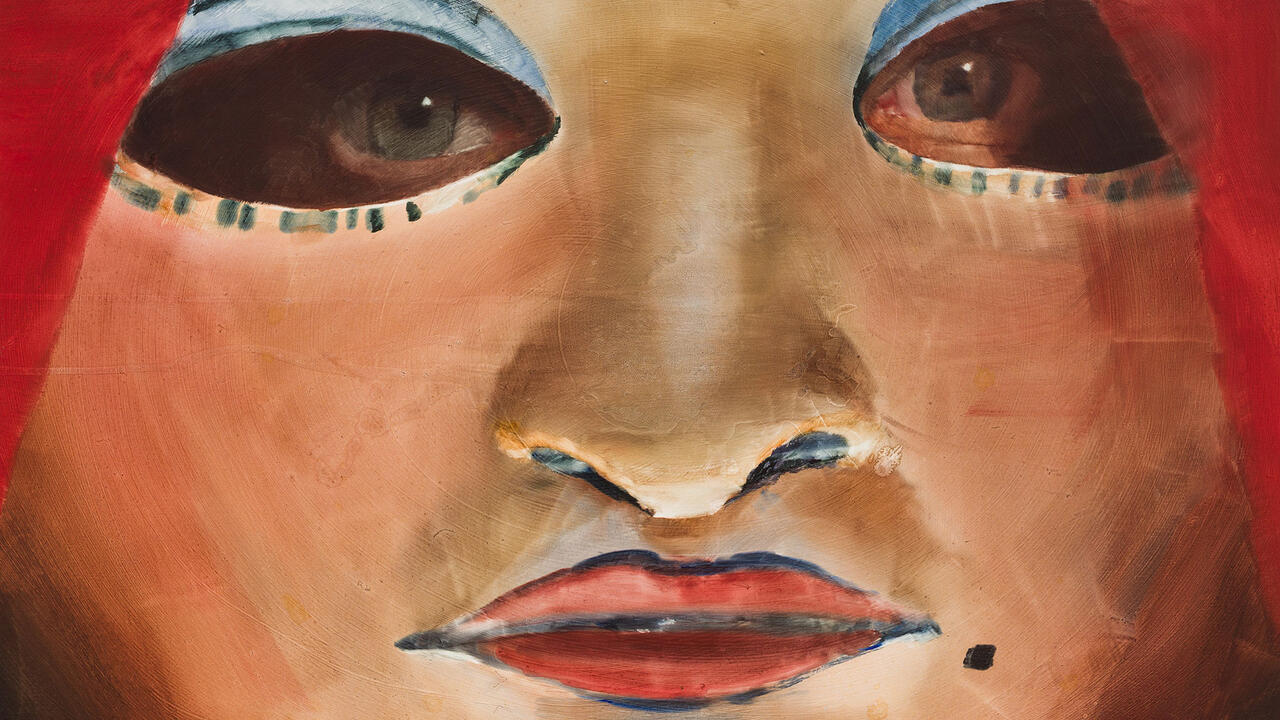

Written for piano, violin, cello and guitar, occasionally augmented by more unusual instruments such as harmoniums or elastic bands, Penguin Café Orchestra’s music conjures images of 1970s progressive academics in denim jackets or cheesecloth skirts with lectureships at provincial polytechnics and broods of ruddy-faced precocious children – the sort David Lodge and Malcolm Bradbury satirized in novels such as Changing Places and The History Man (both 1975). Their work shares the same sensibility as that odd brand of British art that includes painters such as Tom Philips or Ian Hamilton Finlay; artists strangely adrift from the canon of international Modernism who would make semi-figurative paintings about, say, the Golden Section or classical philosophy. Song titles such as ‘Pythagoras’s Trousers’ or ‘Perpetuum Mobile’ put me in mind of Brian Eno, whose Obscure Records label released the first Penguin Café album, and Peter Greenaway films – all those clever anachronisms, archly constructed plots and Michael Nyman Minimalist-lite soundtracks. Even the group’s album covers – paintings by artist Emily Young of, well, penguins engaged in various human activities – look like whimsical 1960s psychedelia rather than the sort of flatly literal Surrealism they evidently aspired to be. In some senses the Penguin Café Orchestra sound like eccentric academics – erudite and skilled, if a little aloof from real world realities – yet there is something attractively homespun about them too, a characteristic which in recent years has led to their music having a more nebulous influence on advertising and cinema.

A romantic idealism shaped the Orchestra. The group was formed by composer Simon Jeffes in 1972, after having had a particularly lucid vision whilst recovering from food poisoning. He dreamt of a nightmarish concrete apartment block inhabited by lonely individuals isolated from each other by a highly technological society. The following day, Jeffes went to the beach and had another vision, this time of ‘the Penguin Café’, where a kind of spontaneous, passionate, sociable creativity could flourish. Jeffes, whose experiences in the worlds of both popular and academic classical music had left him feeling dissatisfied, began to write the kind of music he imagined would be played in the café. ‘Ideally I suppose it’s the sort of music you want to hear, music that will lift your spirit. It’s the sort of music played by imagined wild, free, mountain people creating sounds of a subtle dreamlike quality. It is cafe music, but café in the sense of a place where people’s spirits communicate and mingle, a place where music is played that often touches the heart of the listener.’

Wild and free mountain music is possibly the last thing you would think of on hearing Jeffes’ ensemble – it is too self-aware and cultured for that. ‘Pythagoras’s Trousers’, for instance, or ‘Music For a Found Harmonium’, which opens with the gentle sounds of a wheezing harmonium and develops into something approximating a celtic folk dance, sound forced rather than instinctive. Although the pieces can occasionally seem like the result of an in-joke amongst classically trained musicians about, say, the use of major fifths in late-Baroque chamber music, at its best the music exudes humour and warmth. It is wonderfully idiosyncratic, simply following its own interests with no care about whether anyone thinks it’s ‘cool’ or not. ‘Air a Danser’, which opens Penguin Café Orchestra, was inspired by Madagascan zither music and fuses swooping string phrases with cheery, easy-going repeated guitar figures. ‘Cage Dead’, composed after the death of John Cage, is simple and languid: a short phrase repeated over and over, carried along by gentle percussion instruments which sound like soft, muted Indian tablas. Pieces such as ‘Nothing Really Blue’, ‘Oscar Tango’ and ‘Numbers 1–4’ are quiet, delicate and controlled compositions for piano and strings, thoughtful studies that never slip into the heart-on-sleeve lyricism courted in pieces such as ‘Air’ or the sweetly titled but cloying ‘Cutting Branches for a Temporary Shelter’.

One2One advert (1996) featuring the PCO’s ‘Telephone and Rubber Band’

Jeffes died in 1997 at the tragically early age of 48, after which the Orchestra disbanded, coming together last year for a ten-year anniversary reunion. Their music, however, has had a lasting influence – not so much on the work of musicians today, but in the broader world of film and advertising. When used by companies as diverse as Eurotunnel, The Independent, The Economist, IBM, Volvo and Hewlett Packard, and One2One/T-Mobile, and in films such as Napoleon Dynamite (2005), Penguin Café Orchestra’s music more often than not denotes a certain kind of whimsy, or kookiness. Their most famous track ‘Telephone and Rubber Band’ (made with a sample of the old busy line telephone signal, rubber band and violins) has now become the template soundtrack for any number of mobile phone, building society or car ads. These kinds of commercial usually depict a demographically balanced cross-section of ordinary people talking about their hopes and dreams, or witnessing cutesy, pseudo-‘magic realist’ phenomena, such as cars inexplicably floating in mid-air, or millions of coloured balls bouncing through the streets. These feel-good moments of collective reverie are invariably accompanied by, if not some singer-songwriter of Vashti Bunyan or Jose Gonzales’ ilk, then Penguin Café-esque music: endearingly folksy but tinged with a little electronica or pulsing, Philip Glass-esque strings, as if to suggest that the high-tech product being sold to you is somehow benign, community-spirited and designed with the greater well-being of the world in mind.

Given Jeffes’ original vision for the ensemble, the uses that have been found for their brand of music strike me as sad. If the Penguin Café Orchestra’s work is the aural equivalent of discussing nuclear disarmament over a lentil bake and elderflower wine in late-‘70s Winchester, then it is now also an elegy to a bygone, more idealistic era.