Jana Euler

Work, Paint, Ask Questions

Work, Paint, Ask Questions

Jana Euler has only painted one self-portrait: Identity forming processes overpainted (2012), which shows a close-up of the artist’s face. Three brushes enter the painting, adding colour to the skin around her eyes. Her gaze – rather than being directed towards the viewer – is distinctly off-centre; disconcertingly, almost shyly, she looks to her right. This gaze seems familiar – from Skype, for example, where the other person never looks you in the eye for the simple reason that the camera and the eye are in different places (or because you’re checking your own camera image in the corner of the screen). A grid of fine diagonal lines lies both over and behind her face; matchstick men in strange poses hang in the grid and abstract comic-style heads in profile: forehead, nose and mouth.

This painting brings together several pursuits in Euler’s work to date: an exploration of the production of identity noted in the title (via a recognizable face), an interest in communication and its breakdown (the skewed gaze) and a specific mode of figurative painting with semi-translucent layers which clearly depict how the painting was made (paintbrushes, grids, study sketches) instead of simply bearing incidental traces of its creation (such as accidental drips left on the canvas). Euler’s approach is also characterized by a tendency towards direct symbolism. Two similar portraits of young women – Omnipresent instincts overpainted (2012) and Social expectations overpainted (2012) – present the eponymous instincts and expectations in almost paradigmatic form: as aggressive animals and as hands holding wineglasses in a distinguished manner.

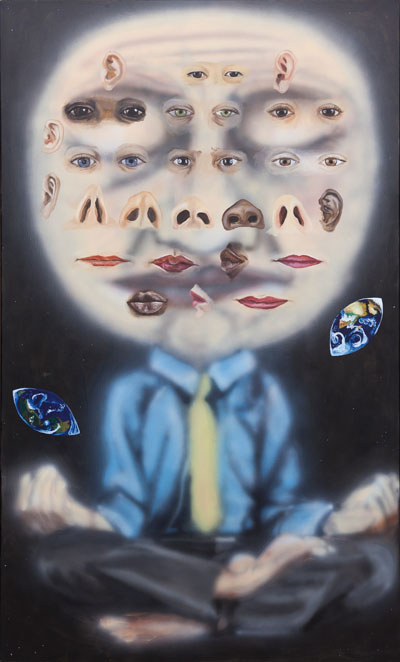

Her literal approach can be seen in other works. How to be more than one without turning Europe back to fascism (2012) shows a meditating manager with a bloated head, who is juggling two sections of a globe. One sees something akin to identikit parts in front of his blurry head: rows of eyes, noses, mouths and ears. Such freely combinable and marketable identities rule the world – or so this painting seems to argue. And it’s probably true, but it’s rare to see facts translated so clearly into paint. Many issues that have been haunting artistic discourse in a somewhat abstract form for years – questions of social capital, communication, networks and roles within society, or the commodification of identity as a recognizable personal brand – materialize in Euler’s pictures in an atypically concrete way. Using the medium of figurative painting, the artist simply and directly says and shows what it’s all about.

But things are not quite so simple or direct. While Euler’s paintings use overly blunt symbolism, they repeatedly conceal their messages. Many crucial details emerge only after a second glance. Consider the statement the artist hid on the grotesquely inflated faces in the series The B-motions sending undeliberately a strong message (2011) which addresses how her identifty has been defined and fixed as a painter (‘being the medium is exhausting’ reads the statement). Or take the question mark sometimes formed by the eyes in her faces, as in From a man without qualities to a man with a mission (2012). In Communication-process out of focus (2012), she portrays communication as a circle of stick men blowing empty speech bubbles into each other’s ears, but they are painted so blurrily that the motif can be perceived only as a vague hint.

Euler’s programme really gets going only after her seemingly direct answers to the problem of portraying themes become questions asked by the viewer. Am I really seeing what I think I’m seeing? And am I really seeing it like this? As riddles of perception, these paintings harbour a fundamental sense of doubt and become performative by inviting the viewer to solve them. Euler rejects not only the instant identification of the social games she criticizes but also being identified with the stereotypical identity of a critical painter. Her works hide in the bright light of over-exposition, vanish in the surface and discover the last remaining possibility for making oneself invisible in an age of exposure.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell