Jeffrey Vallance

Centre d‘Édition Contemporaine

Centre d‘Édition Contemporaine

‘Before the beginning, there was only God. Because He was alone in the void, God became lonely and bored. God became so bored that He exploded. God exploded in a big bang.’

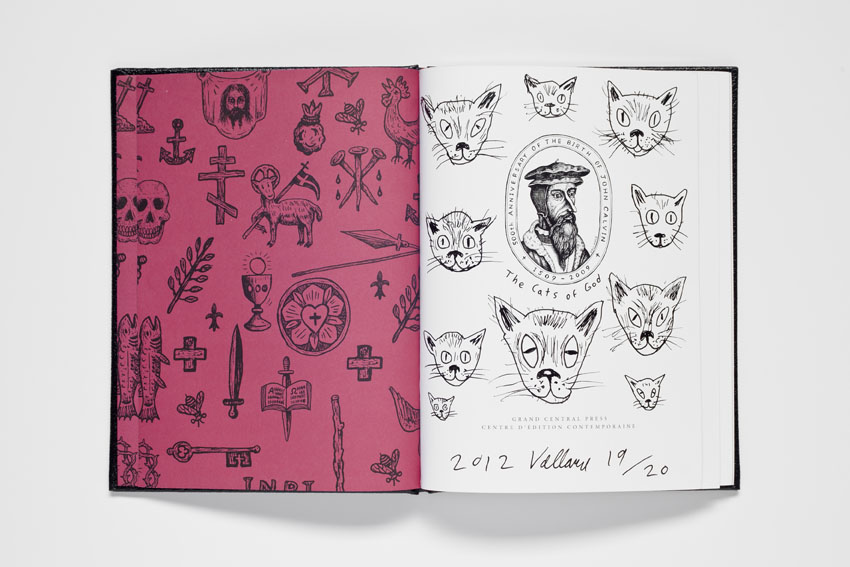

These are the opening words of the gospel according to Jeffrey Vallance, which was solemnly recited as the start of his recent performance in Geneva. The text forms the last section of The Vallance Bible (2011) co-published by centre d’édition contemporaine and Grand Central Press, Santa Ana. After the reading, this long visionary poem on the creation and destiny of all things was discussed with religious and scientific figures in a storied chapel at the heart of Geneva’s old town – an encounter provoking strange dialogues that were less incongruous than they may have appeared.

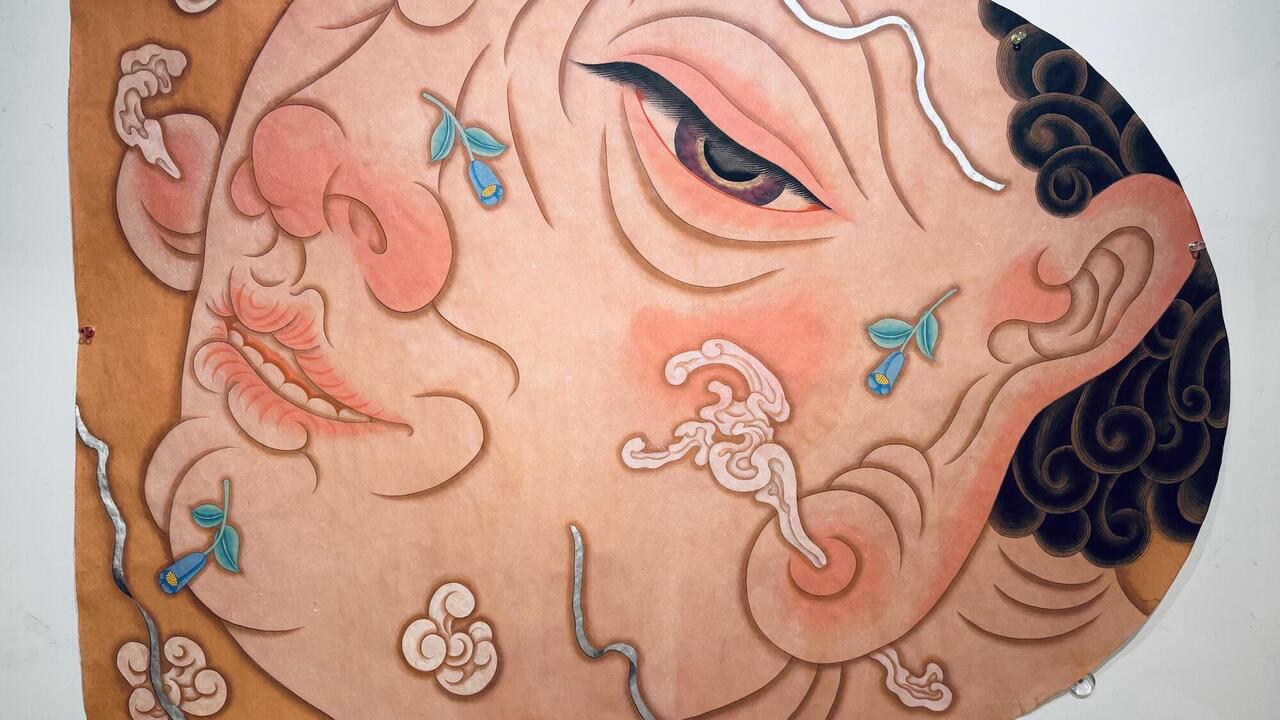

The publication and the accompanying exhibition adds Geneva, the city of Jean Calvin, to the list of stations in the uncertain pilgrimage of this Californian artist who grew up in a Lutheran family. For some years now, Vallance has been developing a personal geography under the guidance of tutelary figures. This led him to a meeting with the King of Tonga, an audience with Pope John Paul II, an exploration of his taste for Elvis Presley and a dissection of his stepfather’s affection for Richard Nixon. In passing, the artist makes fun of the image of himself as a modern pilgrim wandering through a never-ending sequence of souvenir shops. On returning from these various peregrinations, he builds reliquaries and sets his collected fragments of contact in precious caskets.

These objects are supplemented by fragments of the artist’s personal archaeology. Here, bedded on silk cushions, we find not only dubious hand-crafted items purchased in St. Peter’s Square but also the broken neck of a soda bottle blown up by his father at a drive-in one evening when he had forgotten to bring an opener. The rooms of Vallance’s memory palace, it would appear, are packed with objects, valuable and useful.

For this project, Vallance seems to heed the ban on selling relics which was issued by a succession of reformers; instead he embeds scraps of memory within The Vallance Bible itself. The body of the text is divided into three chapters and contains personal accounts of mystic experiences. The first edition – lavishly bound in black leather embossed with gold – also holds a relic: a piece of white cotton fabric supposedly impregnated with the artist’s sweat.

The Vallance Bible may recall the American cartoonist Robert Crumb’s The Book of Genesis Illustrated (2009), although Crumb produced merely an illustrated version of a holy book. By contrast, Vallance does not hesitate to make use of his artistic freedom – respectfully but with courage and humour – by appropriating this most connotation-laden of literary forms. He intervenes in the debate about the truth of sacred texts – a debate that remains politicized, precisely because religion transformed into truth tends to challenge the secular autonomy of the state.