Jennifer Bornstein

In the rambling acknowledgements to his autobiographical novel A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius (2000), Dave Eggers states ‘Here is a drawing of a stapler’ and subsequently presents readers of his memoir with a simple line-drawing of a stapler. This spotlighting of a mundane bit of ‘art’ was not intended to be revolutionary (as it might have been in previous eras). The subtext – i.e., there is no subtext – is cheeky, vaguely hostile and self-mocking, but in the context of Eggers’ on-the-page persona it is also suggestive of a cringingly earnest desire for something more than irony.

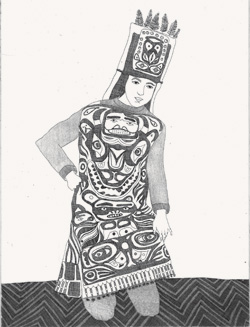

So what do the circular conceits of Eggers’ now infamous stapler have to do with Jennifer Bornstein’s latest solo exhibition in New York? Well, actually, not much. While Bornstein’s intaglio prints of friends, students, random figures and peripheral cultural icons happen to have the Etch-a-sketch look of Eggers’ drawing, their humour conceals no dark burdens, and their juvenile styling conveys no righteous fire. Instead, her images are exactly what they look like: the trial-and-error explorations of an artist trying her hand at a new medium.

Following the success of the colour snapshots and films of gawky adolescents she produced throughout the late 1990s, Bornstein took a job at Yale in 2003 and began to teach herself printmaking. The 55 vignettes displayed at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise are therefore a catalogue of her evolving familiarity with etching. Each small-format anthropological study contains subjects caught in acts ranging from the mundane (checking an email) to the bizarrely banal (practising kung fu while listening to daytime TV), and all are equally cartoonish. Lines are crude, details vary from meticulous to haphazard, and perspectives are imperfect. To eyes accustomed to the restive agendas of Bornstein’s neo-Conceptual peers, the childlike execution may appear to be a deliberate or sarcastic de-skilling, but over the course of the exhibition incremental shifts in style reveal a telling trend: namely, the later prints are getting better. There is no pretence here: the artist is learning.

Bornstein began the series with a habit of exaggerating one or two details to an extent that nullified the rest. In Teenage Roommate Reading National Geographic (2003), for example, straggly arm hair accentuated by hatched, prickly lines arrests the viewer’s interest, eliciting an almost irrepressible urge to attack the offending follicles with a razor. Similarly, in Bus Rider (2003), tightly wound coils form an oversized afro that reduces the man sporting it to a mere cipher. And when it isn’t hair-play that overwhelms the early images, there’s a niggling hint of assignment that undermines them. The blithely self-evident titles coupled with the prominent inclusion of anthropological items – a Nivea bottle, a Ziggy Marley T-shirt, a cowry shell necklace – repeatedly shift the focus from the subjects to the trappings that define them. Household objects and hipster accoutrements stack up without amounting to anything more than the desultory ‘meaning’ of candid amateur photography.

These tics mellow (but don’t entirely disappear) as Bornstein becomes less self-conscious and more technically savvy. Her lines are cleaner, perspectives are sharper, and shading is accentuated, all of which helps to dampen the awkwardness of fetishistic hair and the scene-stealing, cultural ephemera. In some recent works – such as Study for 16mm Film (Scruffy Guy Lacing up His Sneaker) (2006) – latent movement infuses a new vitality, and in others the ineffable sense of the artist feeling close to her subjects evokes sincere empathy, as in Study for 16mm Film (Guy from the Mall) (2006). When these come together, as they do in Study for 16mm Film (Scruffy Guy with His Cat) (2006), the results are very nearly touching.

Scruffy Guy is an amicable someone, a brother or a boyfriend, caught in a moment when a fat feline is about to spill from his arms. His frayed flannel, torn Levis and New Balance sneakers still run the risk of over-indulging in Pop Americana, but the plausibility and modest charm of the scene seem to insist that he, the cat and the clothing are all just real. At last, one of Bornstein’s subjects comes completely alive, achieving a guileless verisimilitude. Scruffy Guy, in his various forms, provides a winsome counterpoint to the angsty Gen X Zeitgeist that gave rise to Eggers’ book and the kind of artists that Bornstein might otherwise be mistaken for. This is the reward for her risk in appropriating intaglio printmaking without subverting it, and hopefully an indicator of greater risk-taking to come.