Josephine Meckseper

Display; the female form and protest culture

Display; the female form and protest culture

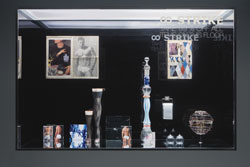

In her signature pieces Josephine Meckseper lines mirrored shelves and fills glass vitrines with disparate groupings of objects, from toilet brushes and underwear boxes to radical literature and pictures of Karl Marx. Her studio in New York’s densely packed Chinatown is likewise surrounded by a hotchpotch of consumer offerings and emporia, including dusty garment stores often tended by elderly women, whose back stock of torpedo bras and thick elastic stockings dates to the 1950s. In a homage to this obsolescence, Meckseper’s recent installations contain items such as cork-soled nurse’s shoes and sturdy stockings purchased from these fast-disappearing stores. Displayed on hosiery legs and featured in photographs inspired by old-fashioned mail order catalogues, these stiff ‘corrective’ underclothes speak of a pre-feminist era. Undergarments like these would become the stuff of second-wave legend, as largely apocryphal tales of bra-burning illuminated a wider cultural turn towards bodily freedom.

Although Meckseper does not consider herself primarily a feminist artist, for the past 15 years her work has consistently examined how the female form is fragmented and displayed. Many of her installations, such as Untitled (End Democracy) (2005), include mannequins hacked off at the waist and thighs to showcase their curvy hips, and her glossy photographs of cool blonde models – wearing gold necklaces with the initials of German right-wing political parties (CDU-CSU, 2001) – mimic the fetish of high-fashion advertising. Additionally, Meckseper’s explorations into the conjunction of politics, packaging and consumerism often make reference to the left’s ongoing obsession with the 1960s and 1970s – the time when women liberated themselves from constrictions both corporeal and societal. The steel wool pads and toilet brushes she uses as sculptural elements in installations such as Untitled % (2005) refer to women’s domestic labour, a signature issue of 1970s’ Feminism, and recall American artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles dusting the vitrines of the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut (Hartford Wash: Washing Tracks, Maintenance: Inside, 1973). While Ukeles performed the daily, grinding work of upkeep, Meckseper’s spotless cases and plastic-wrapped items, divorced from function or use, present a dream world of perpetual sterilized perfection.

Meckseper’s curated assortments mimic eclectic boutiques where carefully chosen products narrate the interests of the consumers that they beckon. We are what we buy, both materially and ideologically, she suggests: this purchased identity extends not only to what we wear but also to what we read and how we vote. She is particularly drawn to the seductions of radical chic; in Untitled (2005), for instance, a white female mannequin is draped with a Palestinian keffiyeh scarf and a designer sweatshirt – highlighting the incongruous interpenetrations of fashion and politics.

Meckseper’s work also functions as reportage: she has extensively documented massive demonstrations against the Bush administration in the US and Europe. One series of photographs, ‘Untitled (Berlin Demonstration)’ (2002), depicts streets teeming with bodies, a phalanx of cops and a burning shopping trolley. In March on Washington to End the War on Iraq 9/24/05 she filmed a 2005 anti-war protest in Washington DC, using 1960s’ film stock; this production choice represents, in a material way, a collective nostalgia for 1960s’-style rebellion – and political possibility – as well as a continuing reliance on perhaps anachronistic modes of representation.

Occasionally Meckseper’s targets can appear too broad: protest culture is full of contradictions, but asserting that politics are subject to the market is not an especially far-reaching insight. Some of her conjunctions – photographs of flag-draped coffins next to Hugo Boss boxes – lean on thin irony and mild shock. She is more successful when she allows for multiple aesthetics or idiosyncratic combinations, as in the stuffed rabbit holding a contradictory sign in The Complete History of Postcontemporary Art (2005). This is also the case in the cult magazine FAT, which Meckseper founded and edited, and which includes a scruffy, vibrant assortment of collages, articles and graphics.

Perhaps Meckseper misses an opportunity to bring her interests in contemporary social movements into conjunction with her feminist concerns. What would it mean to draw a line between mythical burning bras and flaming shopping carts? There are profound historical connections between Feminism and the radical left, but Meckseper doesn’t often examine them. Her focus on anti-war protests leaves little room for the fact that feminists are an important part of anti-globalization activism, or that women’s rights continue to be a source of street battles around the world. Instead, Feminism is limited to its concerns with advertising and the objectification of the female form – a version as potentially outmoded as Meckseper’s 1950s’ undergarments. Or is she enacting a ‘post-feminist’ retooling? (These constrictive girdles could pass as retro-chic fetish gear.) One of the most critical things Feminism offered – and still offers – is a sense of alternative political possibility. It dares to propose that some relations and forms of meaning can resist the rapaciousness of consumer culture.

Meckseper’s insistence on the commodification of protest culture is at times too monolithic, totalizing and hermetic. Even if our longings and desires (whether consumerist, affective or political) are generated within capitalism, that does not mean they are fully subsumed or futile. Being in the market need not be the same as being reduced to it.