Kalifornication

Tracing the ideas that travelled from Germany to the deserts of Southern California, and, eventually, to define the spirit of 1960s counterculture. The remarkable story of the LA Nature Boys

Tracing the ideas that travelled from Germany to the deserts of Southern California, and, eventually, to define the spirit of 1960s counterculture. The remarkable story of the LA Nature Boys

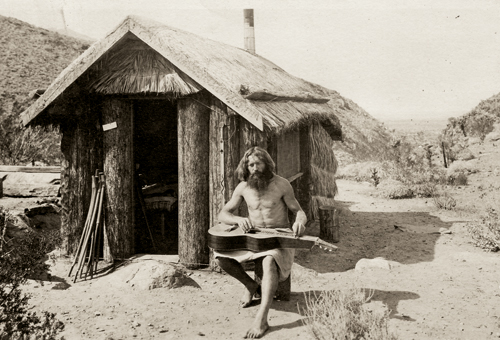

A photograph taken near Palm Springs, California, depicts a long-haired, bearded man sitting on a tree stump playing slide guitar. He’s barefoot and wears a loose wrap around his waist. Behind him is a simple hut he built himself, covered with palm fronds. The man is William Pester. He’s been living in the desert for years, making his own sandals and subsisting on a diet of mostly raw fruit and vegetables. Despite all this, it isn’t 1968. It’s 1917. And he’s German.

Pester, known as the ‘hermit of Palm Springs’, left Germany in 1906 to avoid military service. He settled in Palm Canyon, a couple of hours drive east of Los Angeles, where he took long solitary hikes in the bronze San Jacinto Mountains and sold homemade postcards at a roadside stand. These cards featured health tips gleaned from the philosophy of Lebensreform (life reform), the late-19th century German cultural movement that endorsed a return to nature through practices like vegetarianism, natural healing, and nudism.

Sometime in the 1930s, Pester met a fellow wanderer named eden ahbez in Tahquitz Canyon. Recognizing a kindred spirit, Pester became a mentor to the younger man. Ahbez – who wrote his chosen name in lowercase because he believed that only the words ‘God’ and ‘Infinity’ should be capitalized – was born to a large, impoverished family in Brooklyn and sent by orphan train to live with foster parents in the Midwest. By the time he settled in California he had embraced the freedom of an atypical lifestyle, claiming to have crossed the country eight times by foot.

Besides Lebensreform, other Germanic ideas were finding fertile ground in early 20th century Southern California. Sexauer’s Natural Foods in Santa Barbara, owned by German immigrant Hermann Sexauer, and the Eutropheon, a vegetarian raw food cafeteria in Los Angeles opened by John and Vera Richter in 1917, were centres for disseminating radical ideas imported from Europe. The communities that coalesced around such businesses shared not only dietary habits, but also an interest in learning about alternative health and lifestyle practices. They shared books on naturopathy and healing by Germans like Arnold Ehret, who arrived in Los Angeles in 1914 after running the sanitarium at the Monte Verità commune in Switzerland, Louis Kuhne a.k.a. the ‘father of the detox bath’ and Adolf Just, founder of the Jungborn vegetarian nudist colony and author of titles such as Return to Nature! The True Natural Method of Healing and Living and the True Salvation of the Soul (1896). Such figures promoted ideals that, over nearly a century, travelled from Germany to the deserts and tiny health food stores of Southern California, and, eventually, defined a spirit of 1960s counterculture.

This interest in alternative lifestyles was akin to a religious calling. John Richter regularly gave public lectures about the benefits of raw foods and natural living at the Eutropheon, while his wife Vera wrote cookbooks such as Mrs. Richter’s Cook-Less Book with Scientific Food Chart (1925), which condemned the violent act of eating cooked animal flesh and offered chapters on sun-baked bread and ‘soups for the toothless’. When not wandering the desert, eden abhez occasionally worked as a piano player at the Eutropheon, where he befriended a group of young men with similar views. They too cultivated long hair and beards, practiced vegetarianism and Eastern mysticism, and spent long periods of time in nature where they slept outside, roamed nearly naked, and foraged for food. They became known around town as the ‘Nature Boys’.

Not much is known about this loose group of proto-hippies besides rumours (Jack Kerouac mentioned seeing ‘an occasional Nature Boy saint’ in Los Angeles in On the Road [1957]) and a few photos that show them eating watermelons in a canyon, or playing music on the street, bare-chested and devout. Yet, ahbez found fame in an unlikely manner. In 1948, his song, Nature Boy, as sung by Nat King Cole, became a number one nationwide hit for eight weeks. (The story goes that ahbez passed the sheet music to Cole’s manager, and Cole realized the potential of the unusual melody and haunting lyrics. It has since become a jazz standard.) Some have proposed that the inspiration for the title was ahbez’s desert-dwelling Teutonic friend, William Pester. The lyrics begin: There was a boy / A very strange enchanted boy / They say he wandered very far, very far / Over land and sea / A little shy / And sad of eye / but very wise was he. Ahbez provided the media with an intriguing subject and he was interviewed and photographed – robed and sandled like Jesus – for national magazines during the song’s meteoric rise. Although he continued to make and record music for years afterward, ahbez left the limelight to return to his simple life in the mountains ringing Los Angeles.

Mirroring the mentorship between Pester and ahbez, another popular Nature Boy known as Gypsy Boots also benefited from the influence of a German immigrant. Maximilian Sikinger arrived in the US in 1935 and train-hopped to California after exploring natural healing, nutrition and outdoor living in Germany. Sikinger met Boots (né Robert Bootzin) in San Francisco, and became his mentor, passing along a strain of Lebensreform philosophies to a new devotee. They joined the loose circle of the Nature Boys in the 1940s, during which time Sikinger published a pamphlet on raw food and meditation that sold thousands of copies. Boots, who later became the most widely known Nature Boy, opened the popular Health Hut in Hollywood in 1958. He went on to regularly appear on television on The Steve Allen Show in the early 1960s, where he swung by rope onto the stage, gulped down organic juices, and exercised with the host. As a beloved eccentric, he appeared onstage with many psychedelic bands of the late 1960s, and was widely considered the ‘original hippie’, passing the torch along to a new generation seeking an alternative way of life.

It’s not difficult to see why Southern California would attract early devotees of raw food and outdoor living – where better to enjoy nudism, sun worship, and the ability to eat fruit and vegetables all year round? The dry climate made it a known sanitarium by the 1870s, when tubercular visitors began arriving for sun and mineral springs treatments. As the Western frontier farthest from Europe, California famously held a mythical status for people wanting to escape the ossified traditions of their ancestors and start anew.

But why and how had the alternative lifestyles of the men mentioned above flourished in Germany? Going ‘back to nature’ had other champions in the 19th century (like Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Leo Tolstoy, and George Bernard Shaw), but it was an especially rampant idea in Germany, which had experienced the most extreme pace of industrialization and urban growth of any European nation in the late 19th century. By 1910, Germany contained as many large cities as the entire rest of Europe. As historian Michael Green has noted, ‘the iron cage weighed heaviest, and the fight against it was fiercest, in Germany.’1 Revolts took many forms and were led by a wide cast of players, but a few salient movements, places, and people were most relevant to the subsequent Southern California export.

Toward the end of the 19th century in Germany, the Lebensreform movement grew rapidly. As historian Michael Hau writes of its followers, ‘They believed that modern civilization, urbanization, and industrialization had alienated human beings from their “natural” living conditions, leading them down a path of progressive degeneration that could only be reversed by living in accordance with man’s and woman’s nature.’2

One of the more famous colonies influenced by such thinking was Monte Verità, located near Lago Maggiore in Switzerland. It operated as a loose collection of participants – anarchists, dancers, artists, Tolstoyan ascetics, wanderers, healers, writers – who passed through, perhaps meeting at dawn for a nude sun salute, attending lectures on Theosophy, or living in simple huts in the forest. Attracting many curious parties Monte Verità was also host to widely-known personalities like Isadora Duncan, Carl Jung, Alexei Jawlensky, and H.G. Wells. One founding member of note was Gusto Gräser, born in 1879 in a German pocket of what is now Transylvania. Bearded and beatific, Gräser wandered through Europe with his family in a caravan painted with philosophical slogans, spreading his gospel and giving away poems or blades of grass as gifts. He was frequently imprisoned for spreading subversive ideas. Hermann Hesse met Gräser at Monte Verità and found in him a spiritual guide. In fact, Hesse is thought to have modelled characters in his novels after Gräser’s fierce anti-establishment ways. Hesse’s writing offers another knot in the thread connecting Germany to 1960s US counterculture: his quest for alternatives to Western culture led him to travel to India, which in turn inspired the novel Siddhartha (1922) – required reading for the hippie generation more than four decades later.

At the same time that Lebensreform was spreading, a small group of youths began taking organized nature walks and hikes in the mountains. In 1901 they coalesced under the name Wandervogel (wandering bird). Within thirteen years they counted 50,000 members recruited from schools across the country. Creating a culture that stood in stark contrast to their staid parents, the Wandervogel youths dressed in tattered or loose clothing like capes, romantic collars, and bright scarves, and their hikes extended into long overnight excursions where they would sleep in clubhouses they called nests or anti-homes. They gathered to play folk music, tell stories of medieval Germany around bonfires, and scorn the adult world of obligatory education and toil. A Wandervogel magazine article of 1913 proclaimed: ‘Our people need whole men, not fragments such as notaries, party hacks, scholars, officials, and courtiers.’3

It’s clear to see where the beliefs of the Wandervogel, and the many similar groups that multiplied throughout Germany at that time, reverberated in the anti-establishment movements of the 1960s. But their influence also had other offshoots. Recognizing the power and popularity of youth movements, the Nazi party outlawed them in 1933 in order to consolidate young people under the banner of Hitler Youth. Within a few years, the tradition of organized hiking was replaced with military camps and marching.

Parts of the Lebensreform movement also helped lay groundwork for Nazi Germany’s racist agenda; some of its advocates emphatically linked the health of the individual body as essential to the hygiene and strength of the nation. As historian Christian Adam notes, one of the most popular books during the Third Reich was Hans Surén’s Man and Sun: The Aryan-Olympian Spirit (1936), a photographic study of nude German revellers accompanied by texts on the benefits of nude hiking, mudbaths, and yoga.4 As Adam explains, such images ‘didn’t just hold the promise of freedom. They also held thoughts of breeding – the body as a breeding tool that must be properly trained and fed like a race horse.’5 Even earlier, nudist-advocate Richard Ungewitter, who proselytized that Germanic culture must return to the primitive simplicity of a pre-Christian tribal past, published popular fevered treatises that promoted nudism, vegetarianism, and racial purity. He blamed capitalism, socialism, and the unnecessary use of clothing for the loss of Aryan supremacy.

Ahbez’s popular Nature Boy song became the primary soundtrack for the 1948 pacifist film The Boy with Green Hair, which tells the story of a child whose hair suddenly and mysteriously turns bright green when he discovers that he is a war orphan. After being ostracized by the small-minded residents of his American town, he has a vision of meeting a group of war orphans in the forest who explain that his green hair symbolizes the human costs of war. In fact, a new war is already brewing, accompanied by the fear of atomic devastation. Ahbez’s ardent lyrics repeated at the end of Nature Boy: the greatest thing you’ll ever learn / is just to love and be loved in return, pitted love against war in a guileless dichotomy that was to surface again as a creed of the 1960s anti-war movement.

Ironically, the film came under scrutiny during a moment when support for the Cold War, and paranoia about Communist sympathizers, was on the rise. RKO Pictures purchased The Boy with Green Hair before its release, and proposed that certain lines of dialogue be modified to suggest the need for preparedness for war, rather than condemnation. The script changes ultimately altered the storyline too much and were dropped – yet soon afterward the director, Joseph Losey, was blacklisted.

That the film’s message of peace and tolerance could be framed as un-American – as the pursuit of natural living was distorted by German fascism a dozen years earlier – clearly displays how idealism is so often warped to serve contemporary power interests. And so, the seeds of a desire to live simply, healthily, and in harmony with nature, sown in two nations, grew into very different vines.

1 Martin Green, Mountain of Truth: The Counterculture Begins, Ascona, 1900–1920 (Boston: Tufts University, University Press of New England Hanover and London, 1986), p.59 2 Michael Hau, The Cult of Health and Beauty in Germany: A Social History, 1890–1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003) 3 Richard Miller, Bohemia: The Protoculture Then and Now (Chicago: Nelson Hall, 1977), p.148. Emphasis mine 4 See Karl Toepfer, Empire of Ecstasy: Nudity and Movement in German Body Culture 1910–1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), p.33 5 Interview with Christian Adam, Naked Nazis: Book Reveals Extent of Third Reich Body Worship, on Spiegel.de, 16 June, 2011