Katya Sander

Privet hedges, capitalist rashes, toilets and feminist graffiti

Privet hedges, capitalist rashes, toilets and feminist graffiti

The story of the suburb seems to be based on the idea that nothing should happen within its supposedly sheltered confines. In contrast to urban space, which is busy, noisy and constantly shifting, the suburb’s physical and psychological environments articulate a grammar of harmonious co-existence, a kind of exalted stability.

In Denmark the idea of suburban security is epitomized by the privet hedge commonly employed to demarcate the family home (hence ‘privet fascism’, the slang term for middle-class narrow-mindedness). An almost imperceptible presence, the hedge acts as the perfect territorializing device – something Danish artist Katya Sander alluded to astutely in Safety Graffiti on Hedges (2004). The denizens of a satellite town in the province of Odense awoke one morning to find that drawings of Heimlich manoeuvres, evacuation routes and fire precautions had materialized outside their houses: Sander had made her mark on suburbia by spray-painting first aid instructions and emergency procedures on privet hedges. Until rain or shears did away with them, these peculiar white images lingered as markers of a fear of catastrophe and collapse that, while initially appearing antithetical to the suburban ethos, is, ultimately, but one of the many factors underpinning the psycho-geography of suburbia.

Sander’s works are often détournements that twist significance or explore forms of communication lurking in the recesses of language and everyday life. In a recent intervention, Capital Failure (Sold) (2006), the artist arranged for thousands of little red ‘Sold’ stickers to be placed on price-tags in shops in Copenhagen (without obtaining the owners’ prior permission). She then exhibited photos of the doctored tags at the Charlottenborg Exhibition Hall, alongside another 70,000 ‘Sold’ stickers that had been printed at the same time, implicitly prompting gallery-goers to take them and put them to similar use, although the gallery assistants, when asked whether this was the case, would only reply ‘there are no instructions’. With so many goods seemingly unavailable, the stickers effectively undermined the buying power of the consumer: no matter how wealthy a customer might be, no matter how well-stocked the shop, it was impossible to acquire anything. Turning its own devices and locations to her advantage, Sander succeeded in temporarily destabilizing the free market with her Yayoi Kusama-esque capitalist rash.

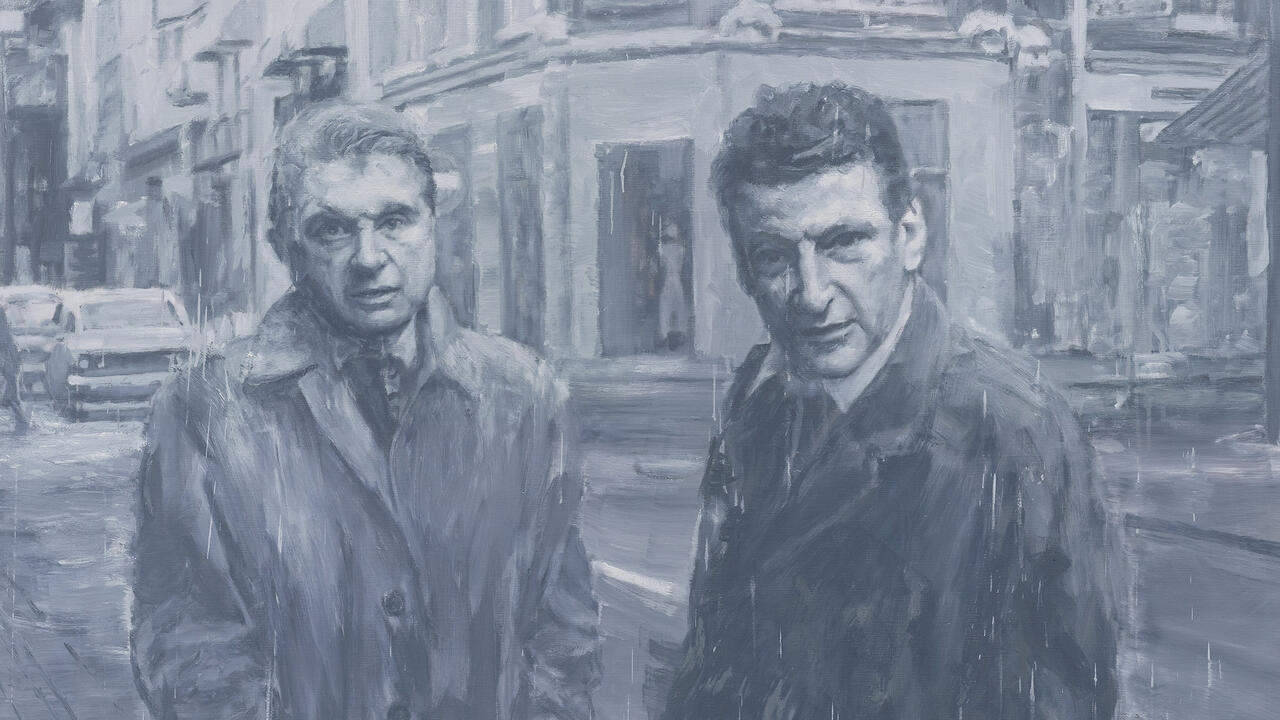

In the video installation Exterior City (2005) Sander addresses the question of how agency can evolve into resistance. A woman is seen walking purposefully around social housing estates in Vienna and Malmö, fly-posting placards onto doors that also function as portals connecting the two cities. In German and Swedish the posters address ‘workers, bosses, tenants, landlords, sympathizers, citizens’, as if the woman were the vanguard of some unnamed movement about to launch a major operation affecting the whole of society and requiring their participation. Between the two real and defined urban spaces of Vienna and Malmö, Sander evokes a third, imaginary city – the exterior city – which she describes as ‘the space […] where flows of capital, labour and desire exist before being projected onto a grid, before rationalism, before the map’. During the course of the film this third city gradually becomes visible, its physicality charted. Unlike the concrete realities of Vienna and Malmö, with the municipal rationality of their social housing blocks, the exterior city exists beyond these physical limitations, opening up new spaces and vistas.

The urban landscape is also the inspiration behind If I Give You a Name, Will You Give Me One? (2003), for which Sander undertook a citywide linguistic field study. Names and bits of text copied from the walls of public toilets were quoted in a form of sexually charged, fragmented poetry. An extract from one work reads: ‘take me to your bleeder pony earthling / the power of killmaster is coming soon to a brain near you / bleeder / smile you are butt / you are sweet and soft – USA / caka dirt cike’ and so on. In exchange for the names appropriated from these public spaces, Sander wrote a series of questions in the toilets of the exhibition space and in the graffiti’s original locations, taken from the work of American feminist Judith Butler: ‘And what if one were to compile all the names that one has ever been called? Would that not present a quandary for identity? Would some of them cancel the effect of others? Would one find oneself fundamentally dependent on a competing array of names to derive a sense of oneself? Would one find oneself alienated in language, finding oneself, as it were, in the names addressed from elsewhere?’ In Sander’s name game a space is created beyond exclusion and intimacy, where a giving and taking of monikers occurs without either the benefactor or the beneficiary being present. Those names on the wall are just waiting to pounce on whoever is ready to invent a new alias for themselves and their desires.