Living Legacies

Although their activities and missions are multiple, the foundations dedicated to New York’s artists all keep their founders’ visions alive

Although their activities and missions are multiple, the foundations dedicated to New York’s artists all keep their founders’ visions alive

“To be hybrid anticipates the future. This is America, the nation of all nationalities... .” It is 1942. Isamu Noguchi types, his pages stained and creased in thirds, these words enfolded into parentheses, as if uttered in whispers. He is writing an essay about why he has chosen ‘lock up’, joining other Japanese-Americans involuntarily held in an internment camp in the Arizona desert.

The essay takes Noguchi months to write: too many months, and there are too many ideas; it is never published. But today, the sheets poignantly fragile, it is visible behind protective glass as part of ‘Self-Interned: Noguchi in Poston War Relocation Center’ at the Noguchi Museum in New York. Though it was planned more than a year ago, the exhibition feels hauntingly prescient in the America of 2017.

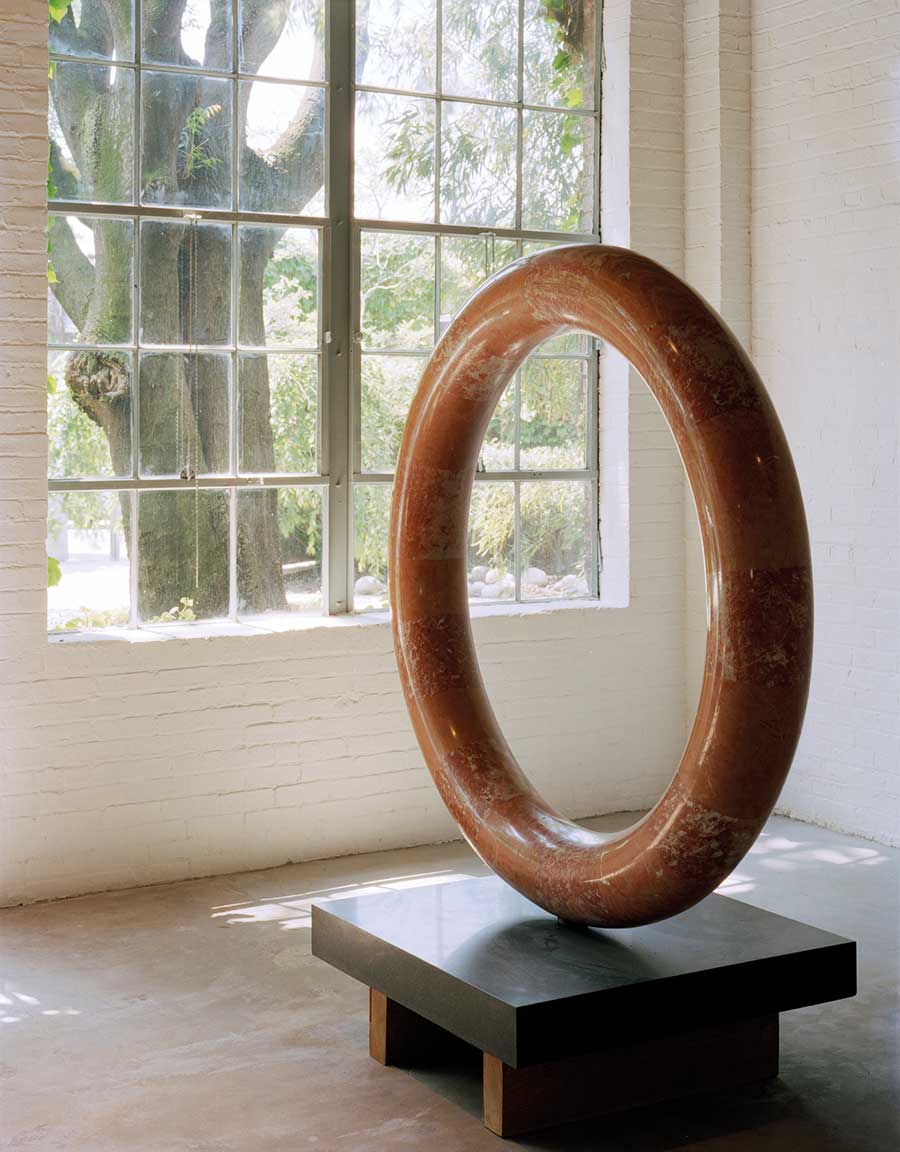

Here, in the industrial building in Long Island City which Noguchi himself converted into an artwork, a home for his museum, a space to protect his ideals, I am looking for ghosts, for guides – for history to give me some hint of how to act now. That the past will o er a way into the present is implicit in the idea of artists’ foundations, whose collections are the subjects of the Frieze New York marketing campaign this year. Spread across the city’s atlas – from here in Queens, to the Judd Foundation in his old home in SoHo, to the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation in a purpose-built space in Chelsea – I want to find in these foundations a map for this moment, also.

The artists whose legacies these foundations are dedicated to lived through McCarthy witch-hunts, escaped Nazis, and stood against racism, censorship and injustice. Staring at the keystrokes of the ‘lock up’ essay, I imagine Noguchi typing in 110 degree heat, in a camp where the food was so poor everyone was sick. A petition displayed nearby demands that Noguchi lists, ‘At least 2, and preferably 5, Caucasian references.’ He types out three names including the US Attorney General in Washington. To questions about his Japanese father, Noguchi’s response is a few terse words: he last saw him when he was three.

A letter from months later is almost empty of hope. So much of the artist’s life is laid bare between these lines: the half-sister who is his only living relative, the father who abandoned him – and above all this idea that a Japanese-American with a Scottish-Irish mother could commit himself out of patriotism, hope, as well as of anger... . “To be hybrid”, indeed. On a rainy day in January, this feels like a picture of my country, as well as an achingly personal portrait of Noguchi. These documents let me conjure him in a way more clearly than his art or his famous lamps and coffee table could.

It’s a kind of communion with the dead. Artists’ foundations keep their founders alive – which means, variously, conserving work, authenticating and cataloguing it, maintaining archives and encouraging scholarship. But guarding legacies in the broadest sense means maintaining values. The Pollock-Krasner Foundation o ers grants to artists in financial need, rewarding long, often hard commitments to the making of art. The Keith Haring Foundation, for example, continues to fund causes that were close to the artist’s heart when he founded it in 1989, a year into his diagnosis with AIDS (a year later, he was dead, aged 31). Having designed posters for ACT UP and made murals for childrens’ hospitals in his life, the Foundation funds organizations supporting at-risk children and AIDS research. These efforts feel urgent now. In the corner of one of the Frieze campaign images, I study a sheet of Haring’s smudged fingerprints, taken by the police after an arrest.

On the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation’s website, I read the artist’s statements on yellow legal pads. The handwriting’s deliberateness makes obvious how hard composing these lines was with his dyslexia, as well as how much it mattered to lay out his thoughts on teaching or photography and isolation. There’s a photo of Rauschenberg in the Navy in the 1940s. Sepia-tinted, he smiles young and open, as if looking out from another country. In 1989, as the “culture wars” were heating up, he would write about the importance of art’s freedom from political interference, talking about fascism and Black Mountain College, where Rauschenberg studied from 1948. He was taught there by Josef Albers, whom he called “a beautiful teacher and an impossible person.” Josef and Anni Albers had arrived in the USA in November 1933, the year Hitler seized power. “The job of the artist is to keep the individual mind open, discouraging a mass agreement on an enforsed point of veiu... .” His notes in the margin of the pads crossed out, Rauschenberg’s misspellings are moving testimony to the care taken in writing, aged 64.

These thoughts are a part of the goal of his foundation – still headquartered in the former Catholic mission on Lafayette the artist purchased as a home and studio in 1965 – to recreate the environment of intellectual openness that Black Mountain College had fostered. Part of its program includes a residency, hosted in Rauschenberg’s studio complex on Captiva, Florida. In keeping with the belief that ‘artistic practice advances mutual understanding’, Captiva hosts visual artists from across the world – the 2017 roster numbers LaToya Ruby Frasier, Liz Glynn and Senga Nengudi– as well as practitioners in other elds: playwrights, choreographers and the writer Hilton Als. There is even a residency to promote environmental awareness, important given that Captiva itself is a barrier island in the Gulf of Mexico, where climate change will bring rising oceans levels.

Rauschenberg set up his Foundation while he was still alive, in 1990. Judd envisioned his already in 1977. Then in his forties, he wrote that museums were moribund. He wrote often too of politics and principles. His foundation has his library of 13,004 books. Last year, the foundation co-published Donald Judd Writings with David Zwirner Books: over 1,000 pages including not just essays like ‘Specific Objects’, but Judd’s take on politics, localism and the role of a citizen, all culled from 35 boxes of notes, just one small part of the thousand-plus linear feet of records in his archive. The Helen Frankenthaler Foundation is currently processing the 300 linear feet of her archives, including documents from her childhood. The layout of the Frankenthaler Foundation’s modern oor in a building on 26th Street was designed to pivot around the storage and research rooms, so that going anywhere in the building means passing by the archives, the Foundation’s Director, Elizabeth Smith, has said. The Noguchi Museum holds 600,000 pieces of paper, even the artist’s checks.

Thinking about these, I wonder how an artist decides what to keep. Or, when to begin? I’ve been going through my parents’ things and thinking of their lives; they weren’t famous, not artists, but they were organizers politically and otherwise. They were the same generation as Judd and Frankenthaler and Rauschenberg, and fought for progressive politics too. Going through their home this past year, I’ve wanted to hold onto everything and have no idea what to keep. If you were interned like Noguchi, what would you hang onto? How would you decide? There is, of course, potential hubris in keeping everything. But it’s my – our – luck that these artists did.

On the phone from Marfa, Judd’s daughter Rainer and I talk about our parents’ ideals and trying to hold onto them. She likens the process of sifting through these old things to someone “dumpster diving” and finding gems as so much in our country and culture gets thrown out and forgotten. “Knowledge,” she says, her voice rising, “is fleeting, and we’re not very good in this society at holding onto good ideas. They’re forgotten and tossed out. If we were in a culture that had a stronger structure for libraries or just even meeting to discuss what ideas are important to continue” – she laughs – “we could then just go do a crossword puzzle.” Instead she stewards that history. Along with her brother Flavin, she’s been shepherding the Judd Foundation since she was 24, for half her life, but she’s also a filmmaker, and working on the foundation hasn’t always been easy. She tells me, “Don was an audacious thinker, and I think what an honor this is, what a great laboratory for ideas.”

Through the Foundation the Albers created in the early ’70s in the service of ‘the revelation and evocation of vision through art’ I find a photo of the couple in 1933 aboard the SS Europa to America, their hands clutched, Josef holding their passports. Today, seeing the impact that war and politics had on artists like them or Noguchi or even Rauschenberg, their foundations feel like refuges: like worlds constructed in response to one that had failed. On SoHo’s Spring Street, you can walk through the building Judd lived in just as he intended. Lucas Samaras’s Box #48 (1966), sealed with knives stuck into its top and sides, remains right next to his bed on the floor. On one of the guided visits offered to the public, I walked through each oor, Judd’s kitchen and studio and bedroom. The glass is thick, the sounds of the street stilled, and everything inside is placed carefully, just as Judd left it – not only the art, but the kitchen utensils, even the bottles of whisky.

Oil stains seep through the floors, spectral hints from its industrial past (at the Pollock-Krasner House in East Hampton, the floor is splashed with the artists’ paint drippings). The building holds its breath. Then, behind a small partition screen on his studio floor, I spy a stack of Harper’s where the artist would sit to read, and suddenly I see him writing here: picture the bright yellow sheets on which he scribbled out his ‘General Statement’ in 1971, the quick scrawl of his urgent cursive. “Everyone has to act, has to accept the power that’s theirs, otherwise they’ve given it to someone else.”

This way of touching the past, touching documents, paper, words, letter-marks and scratches and smudges, is where I feel history sigh and open. It comes alive for me. Under the bright lights in the Frankenthaler Foundation, I read words scribbled in pen: “Pliz come, luff H.”

Frankenthaler wrote them in 1951, at the bottom of a poster Franz Kline designed for the 9th Street Exhibition that would launch the New York School. She is 22 and about to be in this show that will set history – a year later she will make Mountains and Sea (1952), with its soak stain spreading out. Noone today knows who she was asking to come to the show, but those marks of hers evoke something different the paintings I grew up seeing as a kid in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, or even her tools (three sponges, four tubes of paint and a turkey baster), temporarily displayed here in another room at the Foundation. It’s someone young and playful, and welling with pride. It is “Pliz come.” It is “luff.” The moment summons the artist, and makes her a guide. This is what I am here for; this is what these foundations are here for, too.

Flavin Judd speaks with Stephanie LaCava for Conversations on Collecting at Frieze New York on Sunday, May 7, 4:00-5:00pm.

Conversations on Collecting take place in the Deutsche Bank Wealth Management Lounge within the fair, and are open to all VIP guests.