London in Six Easy Steps

‘Six curators. Six weeks. Six perspectives.’ The strap-line for the ICA’s sketch of contemporary art in London – the most seductive, sick, exhausting and exhilarating of cities – was a deliberate acknowledgment of partiality. But how could it be anything else? Art communities tend to be small (but with a gravitational pull that can delude their constituents into feeling their scene is vastly important), and a cataloguing of every artistic murmur in London would be boring beyond belief. (What is it with the art world’s pathological impulse to taxonomize everything?) But with each show lasting only a week, mutterings could be heard that it was all a little too easy, a sleepy mid-August act of space-filling. The series was garlanded with brightly painted exhibition signage – Union Jack colours and London Underground typefaces – like a throwback to the mid-1990s’ capital of yBas and Britpop. Mercifully, the ICA stopped short of dressing its invigilators as Beefeaters, yet for all the usual curatorial flummery about multi-layered urban spaces, socio-political weather systems and ‘shifting realities’ (my cognition of ‘reality’ always seems to stay the same – are curators actually multi-dimensional beings, I wonder?), London remained elusive.

In his otherwise engaging essay prefacing the exhibition catalogue, the ICA’s Director of Exhibitions, Jens Hoffmann, rather condescendingly described London as a city with ‘a nascent contemporary art scene that has yet to establish a firm terrain’. A strength of ‘London in Six Easy Steps’ was its broad generational sweep, both in terms of participating curators and exhibition content; this at least went some way to refuting his odd remark, which was perhaps a subconscious conflation of ‘scene’ with ‘market’. Although contemporary art in Britain has certainly become more visible since the 1990s, London itself has long harboured a large number of artists. That their profile was not always as fashionable as other international art hubs in the 1970s and ’80s is no basis to deny the existence of a scene. Gilane Tawadros’ sober but fascinating show ‘The Real Me’, for instance, took identity politics in 1980s’ London as its subject matter, while Guy Brett’s ‘Anywhere in the World: David Medalla’s London’ looked at one artist’s experience of the city since the 1960s. ‘Even a Stopped Clock tells the Right Time Twice a Day’, curated by Tom Morton and Catherine Patha, reached as far back as Wyndham Lewis, via 1960s’ British Pop artists Colin Self and the late Eduardo Paolozzi.

The first ‘step’ was made by Catherine Wood, whose ‘Emblematic Display’ advanced the idea of a form of heraldic representation for each artist; a ‘compressed structuring’ that reflected the fast turnaround of shows. Including work by Pablo Bronstein, Cerith Wyn Evans, Mark Leckey, Daria Martin, David Thorpe and Jannis Varelas, it focused on artists who treat the city as a specifically aestheticized realm. Ring-fencing much of the gallery floor space, Bronstein’s knee-high wall (Concept for a Public Square, 2005) made navigation around the gallery awkward, articulating an acute point about the easy appropriation of city identity as a subject for exhibition-making.

B&B (Sarah Carrington and Sophie Hope) followed up with ‘Real Estate: Art in a Changing City’, a densely packed show essentially concerning the quandaries of urban gentrification. Although not without interesting contributions (book-ending the show, Adventures in the Valley (Ongoing), Polly Braden and David Campany’s photographic study of change in east London’s Lea Valley, and Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson’s Docklands Community Poster Project, 1981–91, were notably engaging), the exhibition format fetishized the presence of reams of information and print-matter at the expense of coherent, clear communication, making the experience not unlike visiting a chaotic, if earnestly run, library.

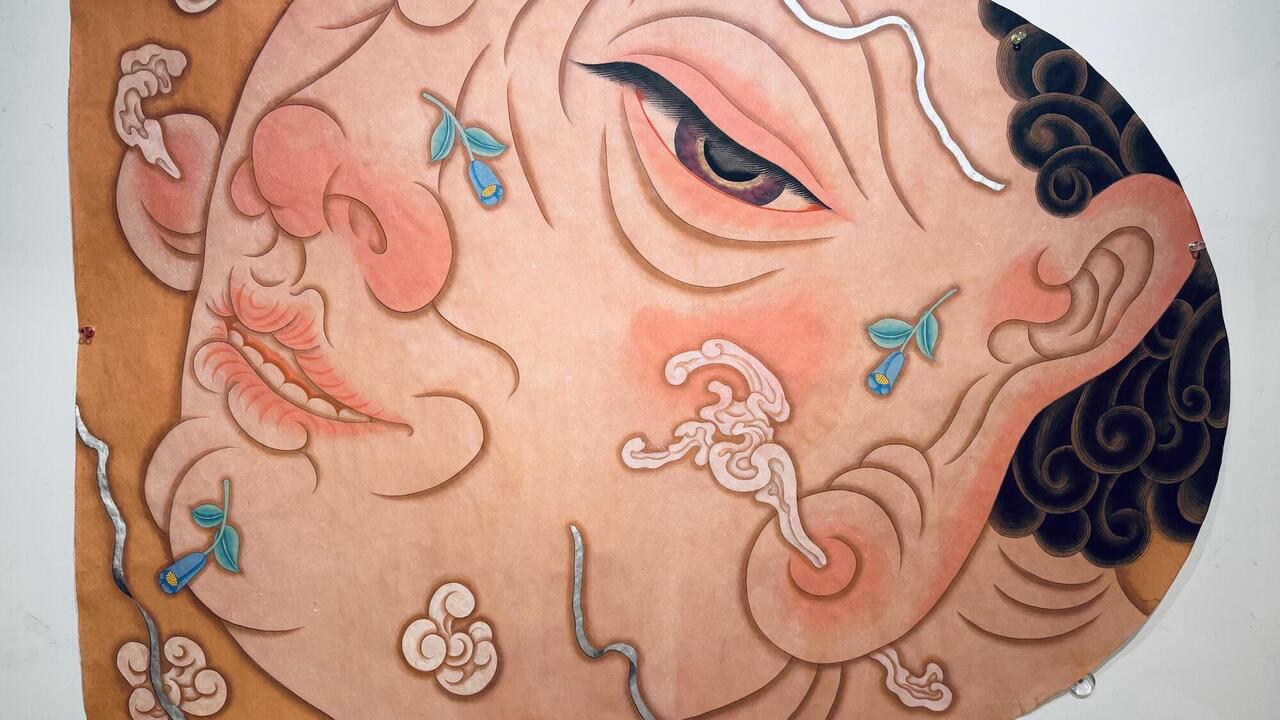

Morton and Patha’s episode was more poised. Using a theatrically lit display model redolent of an early Surrealist salon hang, it risked affectation, yet the inclusion of historical works alongside those of younger artists such as Steven Claydon, Gareth Jones and Milena Dragicevic lent the exhibition a haunted elegance. By contrast, Brett’s presentation of David Medalla was a riot of objects, colour, movement and activity; a celebration of the artist’s itinerant energy and the ways in which his impromptu performances and fluid, kinetic relationships with other artists have bypassed more orthodox structures in the art establishment. This was followed by ‘The Real Me’, which took its title from a 1986 ICA conference of the same name, which, in Tawadros’ words, argued with ‘the dominant idea of a settled, homogeneous, mainstream identity that could be invoked for the [British] nation’. Including, among others, Black Audio Film Collective’s Twilight City (1987), a powerful documentary recording London’s changing face at the high tide of Thatcherism, alongside Rasheed Araeen’s Ethnic Drawings (1982) and photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe, ‘The Real Me’ performed a subtly critical side-step around platitudes about London’s multiculturalism.

The final chapter, like many an evening, ended in the pub. For ‘The George and Dragon Public House’ Gregor Muir enlisted Richard Battye (landlord of the abovementioned drinking spot), Pablo Leon de la Barra and ‘friends and customers’ of this east London boozer to transplant its heady atmosphere to the ICA. Fun though it was (I won a pair of jeans in the opening night raffle), it demonstrated how a specific dynamic of people and place (‘east London’ has become a nebulous tourist shorthand for a woolly notion of co-habiting creative communities) evanesces when put under the microscope, making the dynamic in question seem hermetically encoded to the outside world, and the host institution’s efforts wincingly akin to watching your parents disco dance.

The ICA has a venerable heritage, yet its position in regard to London’s artists today still stands at an uneasy remove. Each of the six shows was self-contained; engaging on its own terms but hardly a barometer of art in this city. London remains as indefinable as ever – which is the way it should be.