Looking Forward 2018: Europe

Kirsty Bell, Ahmet Öğüt, Ming Wong and Slavs and Tatars share their highlights of the coming year’s shows: can we break with art-business as usual?

Kirsty Bell, Ahmet Öğüt, Ming Wong and Slavs and Tatars share their highlights of the coming year’s shows: can we break with art-business as usual?

Kirsty Bell

Ahmet Öğüt

Ming Wong

Slavs and Tatars

Kirsty Bell is a freelance writer and contributing editor of frieze. She lives in Berlin, Germany.

The very idea of looking ahead at this point in time seems fraught with anxiety at the prospect of more bad news. Is there a way in which to usefully navigate the fast-moving currents of negative news-streams? Can ideas, artworks, exhibitions, words make a difference and break through the echo chamber’s reinforcement of polarisation? Can they help to make a change?

Within the art world, some changes are happening. Bullying behaviour and harassment is being called out here too, while some of its standard practices are being called into question. Documenta 14 managed to break apart the large-scale exhibition and insisted on a radically differentiated viewing experience which defied consensus. Berlin’s Preis der Nationalgalerie was discredited by this year’s four nominees, who (in an open letter) denounced its use of diversity as a public-relations tool and the promise of exposure in lieu of adequate remuneration for artists. This and other such prizes assert ‘competition between people who are not in fact competing’, as they said, a practice which seems less and less relevant at a time calling for solidarity over division. In 2018, the Carnegie International will be the first exhibition to adopt the pay scale determined by W.A.G.E., guaranteeing evenly distributed remuneration to participating artists as a rebuke of speculation as a form of payment in the nonprofit sector.

The artists and exhibitions I look forward to in 2018 all propose a break with art-business as usual in some way, whether shifting canonical views of what an artwork can be, to divorce it from its role as a speculative commodity in a saturated and self-regarding market; or opting for collaborative practices rather than signature solo works. While this might not be enough to bring about large-scale change, they manifest differentiated views and possibilities through which art and life might be reconciled.

In March, London-based artist Marc Camille Chaimowicz (whose not-to-miss show ‘One to One …’ at Hannover’s Kestnergesellschaft is on view until the end of January) opens his first museum show in the US at New York’s Jewish Museum. For over forty years, Chaimowicz has been making work about the work of being an artist, and striving to dissolve the boundaries not only been art, décor and applied arts, but also between public and private realms: between art and real life itself. His show at the Jewish Museum, itself built originally as a family home in 1908, will bring together artworks, interiors, textile, furniture and wallpaper designs and feature his seminal 1978 work Here and There … as a historical lens through which to read the various materials this exhibition gathers. The dichotomies his work began to pry open in the early 70s are still out there; through its seductive veil of ornament, patterns and pastel tones, the questions it asks are more urgent than ever.

German-born, New York-based artist Nick Mauss is another boundary crosser, as shown to mesmerizing effect in his collaborative involvement in the 2016 exhibition and accompanying publication about Ballet Russes stage-designer Léon Bakst. For his March 2018 show at the Whitney Museum, he takes on a hybrid role between exhibition designer, curator and artist to focus on the history of American modernist ballet. The show will include works from the Whitney collection and the Kinsey Institute for Sex Research alongside his own works, and a ballet he conceived in collaboration with dancers. This is an exhibition as thesis in three dimensions, in which ideas about ballet as a potent medium of transatlantic exchange and a pre-queer history are staked out.

A long-awaited retrospective of textile pioneer Anni Albers will open in June at Kunstsammlung Nordrhein Westfalen in Düsseldorf, a collaboration with Tate Modern where the show will travel in October. A student at the Bauhaus since 1922, and faculty member since 1929, Albers’s relegation to the weaving workshop – banned as a woman from painting – did not hold her back. Instead she expanded the possibilities of this medium, through unique small-scale weavings or wall hangings, as well as designs for mass produced textiles and carpets. She was the first designer to have a one-person show at MoMA in 1949, and her 1965 book On Weaving (republished in September 2017 by Princeton University Press) is still a classic.

Also in London in October, the Serpentine Sackler gallery will open a show by Atelier E. B., the collaborative practice of artist Lucy McKenzie and designer Beca Lipscombe. Their investigation into the roles of production, distribution and display within the act of making has led not only to several collections of clothing, but also textiles, furniture, interiors and publishing.

When Wolfgang Tillmans was invited to guest-edit the 2017 Jahresgaben, published annually by the Kulturkreis der deutschen Wirtschaft and Sternberg Press, he began by asking the question Was ist Anders? (‘what is different?’). This became the guiding theme of a timely and useful publication that brings together interviews and articles by cognitive psychologists, financial journalists, politicians and others, along with a scrap-book like redux of Tillmans’ photographs and news clippings. The collected opinions provide insightful reflection and analysis of intransigent problems such as the Backfire Effect or the Echo Chamber of social media. Particularly illuminating is philosopher and author Philipp Hübl’s discussion of polarisation and the emotional foundations of politics, which includes a fascinating description of shame and ‘übersteigerte Ekeldisposition’ (an exaggerated disposal to disgust) as the key to understanding the position of the radical right. An English translation, What is Different, will be released in early 2018.

What is not different in 2017, nor most probably in 2018, is the plight of refugees in Europe. Since 1993, the Amsterdam-based NGO UNITED for International Action has been compiling a list of refugees and migrants who have lost their lives within or on the borders of Europe. Now it totals over 33,300 individuals. Since 2003, Turkish artist Banu Cennetoğlu has been working with this material, under the title The List and in June it will be presented in the UK for the first time, in sites around London as part of her solo exhibition at the Chisenhale Gallery, and in Liverpool as part of the Liverpool Biennial. ‘I don’t consider it an art piece because I don’t edition it, I don’t commercialize it, I don’t sign it,’ says Cennetoğlu. ‘There is no authorship. It’s a document. It is about making content visible through many levels of collaboration.’ Cennetoğlu’s The List is not a guerilla fly-posting action, but a negotiated use of public space to manifest literally the scale of this issue. This November, Germany’s Tagesspiegel newspaper published The List in the form of a supplement; it was 48 pages long.

Finally, I am looking forward to more Kathy Acker in 2018. On the heels of Chris Kraus’s biography After Kathy Acker (2017), the Badischer Kunstverein will stage an exhibition and symposium around her work in September. A necessary iconoclast for our age?

Ahmet Öğüt is an artist based in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Gabi Ngcobo is curating the 10th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, titled ‘We Don’t Need Another Hero’ – it runs from 9 June to 9 September.

The Emily Jacir-curated Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA 2018) – the 10th anniversary of the exhibition is organized by the A.M. Qattan Foundation, Ramallah, Palestine.

Henrike Naumann's solo show ‘2000’ at The Museum Abteiberg, Mönchengladbach, which runs from 11 March to 10 June.

Justin Tyler Tate's ‘Peer2Pickle’ exhibition at Apexart, New York.

And RAW Académie Session 4, at Koyo Kouoh's RAW Material Company, Dakar, Senegal.

Ming Wong is a Berlin-based artist. Recent shows in 2017 include ‘Sunshower – Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia 1980s to Now’ at National Art Center, Tokyo and ‘Shanghai Galaxy II’ at Yuz Museum, Shanghai; ‘Spectrosynthesis. Asian LGBTQ Issues & Art Now’ at Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei. Upcoming shows in 2018 include ‘A beast, a God and a Line’ at Dhaka Art Summit, Bangladesh.

In 2018, I’m looking forward to:

‘Other Futures’ (2-4 February, Amsterdam), which will be the first festival of non-Western science fiction in the world – exploring new perspectives through the work of artists, writers, filmmakers and musicians from different parts of the world. (I will be showing my Scenography for a Chinese Science Fiction Opera project as part of the programme.)

The 10th Berlin Biennale, curated by Gabi Ngcobo and her team (Nomaduma Rosa Masilela, Yvette Mutumba, Thiago de Paula Souza and Moses Serubiri); I hope their ‘plan for how to face a collective madness’ could, amongst other things, shed some light on the way that Berlin’s Humboldt Forum, scheduled to open in 2019, will handle Germany’s colonial past.

The opening of the new art gallery designed by Herzog and de Meuron at Tai Kwun in Hong Kong, on the site of the former Central Police Station–Court–Jail compound. I’m looking forward to a sneak preview during Art Basel HK in March.

Slavs and Tatars is an international art collective, ‘a faction of polemics and intimacies devoted to an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia.’

We’re very much looking forward to the Siah Armajani retrospective scheduled for 2018 at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. The near octogenarian’s oeuvre is a compelling example of contemplative engagement in the US: his reading spaces argue for another understanding of a commons or public in a country too often lacking the basic vocabulary for these. That he brings a Christian faith from a Shi’a country to bear on a tradition of American transcendentalism in his home in the mid-western US makes his work all the more syncretic and unique.

Blackness is too often considered exclusively from an Atlanticist perspective. Sarah Lewis’s forthcoming publication Black Sea, Black Atlantic: Frederick Douglass, the Circassian Beauties, and American Racial Formation in the Wake of the Civil War (Harvard University Press, 2018) extends the discussion of racial formation to the Black Sea by bringing a long-overdue Slavicist lens on African-American studies.

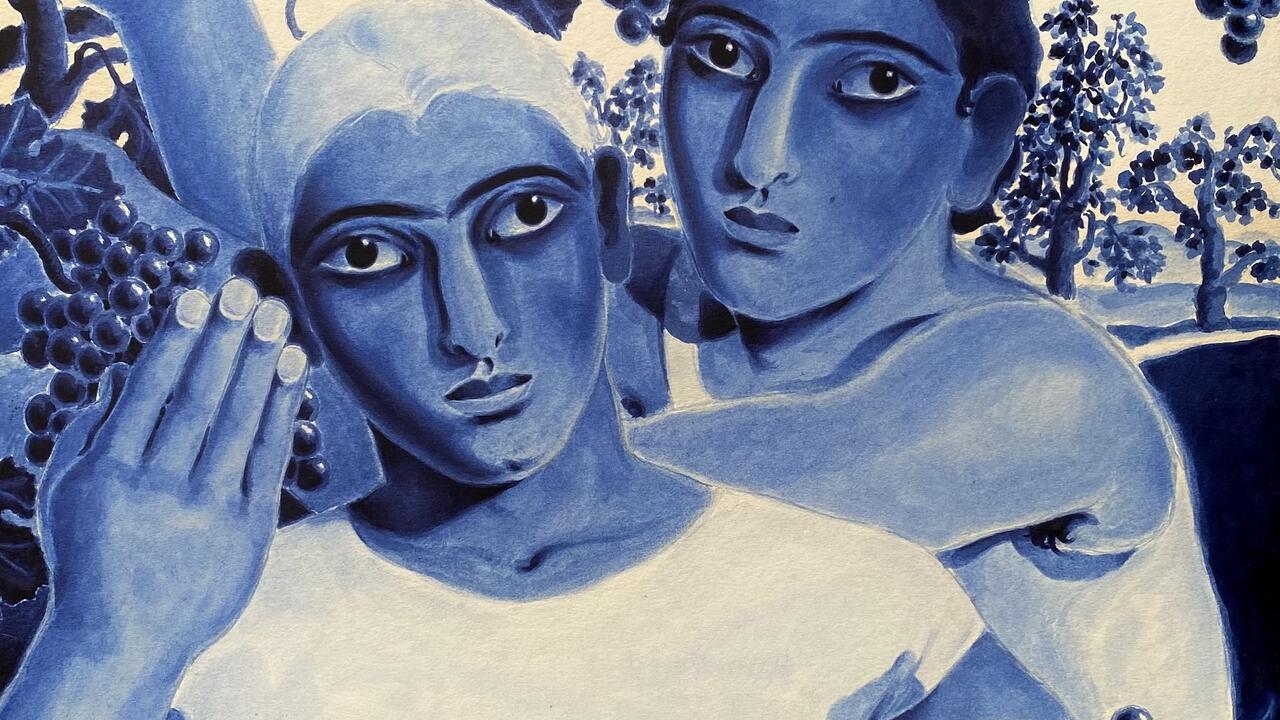

Michael Rakowitz’s The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist on the fourth plinth at Trafalgar Square.

Main image: Michael Rakowitz’s submissions for the fourth plinth, Trafalgar Square. Courtesy: the artist