Lucian Freud

Tate Britain, London, UK

Tate Britain, London, UK

Lucian Freud's retrospective, spanning 63 years of paintings, drawings and etchings, was a unique exposition of the accrual of time, a panoply of significant moments tracing an unimaginable number of decisions. Influences discerned during the 1940s are now well buried within the epic evolution of his work to date. The Painter's Room 1943-4 [no. 10] (1944), with its ripped couch, frazzled yucca and red and yellow zebra's head reaching in through the window, is a classic Surrealist array of the implausible and the theatrical. Plants and furniture still recur in Freud's current work, albeit in an altogether different guise, but he soon dropped the theatrical element in favour of a frankness gradually drained of affectation. During the mid-1940s the subjects of the paintings and drawings settled into the two main genres of still life - usually of plants and dead animals - and single portraits. Dead Heron 1945 [no. 16] (1945) depicts the bird not as corrupted flesh, as Freud might have painted it in later years, but as an idealized, almost atavistic approximation of a mythical bird, its head turned to one side like an Egyptian heiroglyphic. Here the role of painting from life was not one of mimesis but more 'pantomimesis', as the subjects were divested of naturalism in favour of pictorial panache.

The major shift in Freud's work occurred some time around 1956, when he swapped his fine sable brushes for fatter, more loaded, hog's hair. His graphic surfaces broke up into sweeping facets of prismatic colour, with each single brushstroke becoming an emphatic and honest admission of the struggle with paint. Freud did not reckon himself to have a natural virtuosity, but he worked hard to make paint do his bidding. In this sense the work becomes warm-blooded realism, in which our focus of looking moves to the surface of the painting, while the artist's has switched towards the subject. During this self-conscious transition Freud found that 'sometimes when I've been staring too hard I've noticed that I could see the circumference of my own eye'. In many portraits his presence hovers in the foreground, palpable in the attitude of the sitter and the selective nature of his observations.

Although many still lifes consisted of two or more objects Freud's portraits until the 1950s were invariably of a single person. Representing the relationship between sitters - physically, pictorially and emotionally - would be one his most difficult and enduring considerations. Lovers, family members or two entities in a complex social network act as tensile filaments within a metaphorical, pictorial space. Interior in Paddington 1951 [no. 31] (1951), a double portrait of a crumpled, disillusioned Harry Diamond staring through an undernourished and equally jaded yucca, was Freud's sarcastic offering for the Festival of Britain. Elsewhere the sitters seem oblivious of one another, as if painted at different times in a fictional construction. Or, as in Michael Andrews and June 1965-6 [no. 57] (1966), two closely seated people appear to occupy completely different weather systems, emphasizing the strain between the couple.

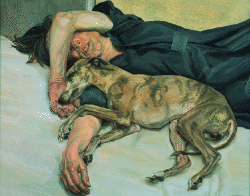

The perpetual battle to reconcile elements, to represent the whole through a series of glances and visual computations, is evident even in more recent close-up portraits. Asymmetrical ears brace either side of a face that, on close scrutiny, is an alien structure. Like the bizarre moment when you've repeated a single word too many times and it ceases to make sense, Freud's familiarity with the human form has corrupted in his visual memory. The reworking of the extremities of his sprawling nudes belies his apparent growing ease with paint. The solid understanding of a ragged couch or the ubiquitous floorboards acts as counterpoint to the difficulty of settling on an expression or the position of a foot, hand or genitals. The predominant beige of the palette, dictated by the ever-present flesh tone, is in fact the intricate negotiation of a surprisingly wide chromatic span. Painting becomes like the construction of new, technological words: pragmatic, descriptive components are welded together to create an irrefutable characterization of their subject. The brushstrokes are small, precarious parts of the whole that creep around the sitters' qualities, delineating them from the outside in.

One of Freud's most reworked paintings is Painter Working, Reflection 1993 [no. 125] (1993). The pigment clusters like barnacles along every part of the body, reaching its highest density at the face and palette, where the 'paint as artist's expression' and 'paint as paint' have been worried into a thick impasto. Deciding on how to represent one's own expression must be, understandably, one of the knottier decisions. Like a swatch of time, the self-portrait illustrates the mounting up of fleeting emotions, displaying a temporal depth that can only be achieved through working from life, when parts of the whole can never be forced into neat resolution.