Lygia Pape

A large open mouth confronted me as I entered the Serpentine Gallery. Highly sexual, verging on the grotesque, the video – entitled Eat Me (1975) – provided a joyful entry into the world of Lygia Pape in this slimmed-down version of the 2011 retrospective at the Reina Sofía (curated by Manuel Borja-Villel and Teresa Velázquez). The Serpentine show focused on a selection of early works that served to display how Pape’s geometric planes of colour later met human absurdity, as her early Neo-Concrete experiments in painting, print and sculpture (from the 1950s and early ’60s) were contrasted against these later performances – including Trio de embolo maluco (Crazy Rocking Trio, 1968) and Ovo (The Egg, 1967). As such, while the Serpentine exhibition comprised an important selection of key works, it could have benefited from a more comprehensive show, given that Pape’s work has rarely been exhibited in the UK.

In the second gallery was a series of colour block paintings (‘Pinturas’, 1954), created with oil and tempura on wood: simple geometric compositions of black, blue, maroon and green layers of shapes floated on white planes. In the next gallery was a series of woodcuts made between 1955 and 1959, all entitled Sem Título: Tecelar (Untitled: Weaving), printed on thin, almost transparent Japanese paper. Here, Pape experiments with positive and negative shapes, ‘cut’ areas mirroring ‘uncut’ areas. In midcentury Brazil, the woodcut technique was firmly entwined with totalitarian politics: ‘Engraving Clubs’ were included in the Brazilian political agenda of the 1950s inspired by cultural policy in Stalin’s Soviet Union. However, contrary to the mass-production of propaganda encouraged by multiple prints, Pape treated her pieces as ‘paintings’, making only single editions.

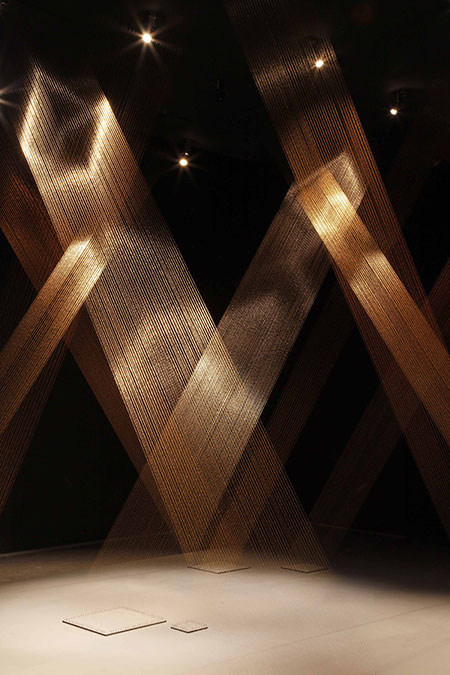

The other side gallery contained the large-scale sculpture-cum-painting Livro Do Tempo (The Book of Time, 1961–3) which is formed from 365 small wooden squares from which triangles, squares and rectangles had been cut and placed on top (and if slotted back together would reform a whole square), to create a three-dimensional relief in primary tones. Accompanying this was the ‘Livro da Arquitectura’ (Book of Architecture, 1959–60), a series of paper maquettes that were ironic takes on different architectural forms with titles such as Grego (Greek) and Barrocco (Baroque), mimicking (although in the most economical way) main characteristics of these periods. The central gallery housed the magical installation Ttéia 1, C (Web) (2002/11): thin lengths of gold string extend diagonally from floor to ceiling, arranged in square columns – each void filled with a shaft of light – forming a larger square in the middle of the room (displayed in the Arsenale as part of the 2009 Venice Biennale, along with a series of small colour block sculptures in vitrines).

Ttéia 1, C (Web), 2002/11, gold thread and lights, installation view

Pape’s early Neo-Concrete works have been compared – almost without exception – to the Constructivists as well as to her Minimalist contemporaries in the US. For example, the artist’s ‘ballets’, made in the late 1950s (a series of coloured cubes, rectangles and tubes in which the dancers were housed moving geometrically to minimalist music) – which, although not on display here, were shown in Madrid – and her other performance works are often likened to the post-minimalist and phenomenological concerns of Robert Morris. In his accompanying catalogue, Paulo Herkenhoff describes such retrospective positioning of Pape within the Western canon as ‘Lygia Pape’s Law’, arguing that Pape was working both prior to and in parallel with Morris and Frank Stella. Had Pape made her works following theirs, it would ‘naturally’ be accepted that Pape’s work was derived from the ‘hegemonic and canonical art’ that came before. Given that this interpretation of her oeuvre still persists, an emphasis should be placed upon extending the ‘language’ of this canon to fully take into account social and political contexts, rather than assimilating work into the existing points of reference.

Much of Pape’s early work may seem wholly concerned with form, but she was more drawn to experimenting with the spaces in between them: curiosity about what happens in the void, gap, opening or empty space underlies all Pape’s work. Divisor (1968) is emblematic of this investigation: a simple performance in which participants slotted into holes in a large square white sheet to walk down the street, forming a collective action and sculpture. This mobilization of individuals from ‘I’ to ‘we’ is a symbolic negation of the void, that is affected literally through the filling of the holes, and conceptually through the filling of the void between ‘you’ and ‘the other’, is a thread running through all of her work, regardless of medium.