Marko Lulic

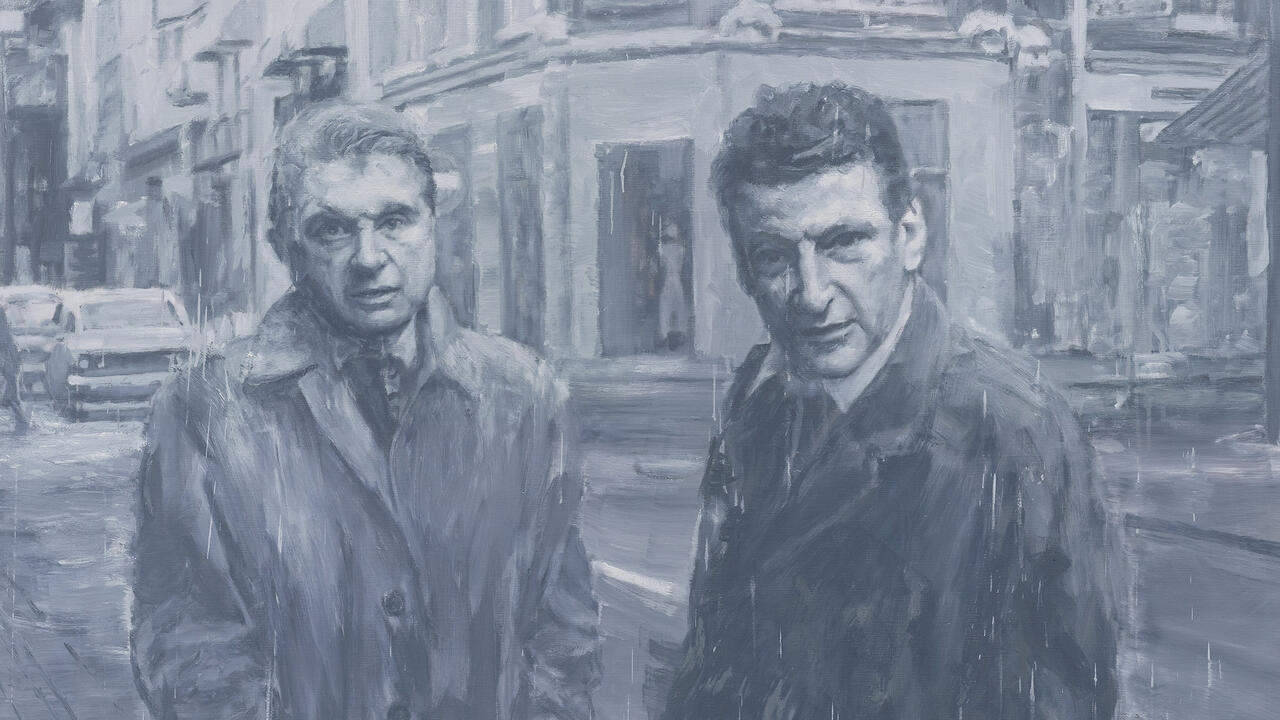

It all seemed simple: an invitation to Marko Lulic's installation 'Unterhaltungsarchitektur' (Entertainment Architecture), which showed the artist posing in front of a mural faintly reminiscent of Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly or Sol LeWitt.

Lulic chose to hold the exhibition in the huge expanse of the ground floor shell of Vienna's future underground railway complex, which, when built, will also house shops, cinemas and fitness facilities. At the exhibition's opening, images from the invitation card became tangible: the artist, mingling with the guests, and the wall with its coloured stripes. Pretty straightforward really - the painter has his photograph taken in front of his painting, which then becomes the invitation to his exhibition.

As is so often the case, the truth is much more complicated - the mural in the exhibition is similar, but not identical, to the one on the invitation. The artist did not pose at the exhibition venue, and so the picture in the exhibition could not have provided the background for the photograph on the invitation. It was, in fact, taken in a Berlin underground station - and it is not known who actually did the painting.

Lulic's gesture is the result of a process of abstraction in which disparate elements are regrouped to form a model: the picture, the exhibition, the artist, the public - and not least the invitation card. The breaks in the staging, caused by the venue and the embarrassingly amateur photograph of the artist supposedly standing in front of his work, all become quotes in a text.

The second work in 'Unterhaltungsarchitektur' was inspired by Ed Ruscha's austerely conceptual concertina series of photographs Every Building on The Sunset Strip (1966). Lulic made a similar record of the Los Angeles street, Sunset und Umgebung (Sunset and Surroundings, 1997) using a hand-held video camera from the window of a moving car. But although the artist may be referencing Ruscha, he explores the theme differently by allowing the city to pass by him as a backdrop. This evocation of driving through LA functions as a complementary piece to the Modernist colour strip mural, which was originally intended to cheerfully decorate the walkways of the Berlin underground system.

For the final element of the exhibition, Lulic projected slides of shopping malls, amusement arcades and betting shops against the unfinished facade of the future entertainment centre. Like the invitation card, these slides become models for what you might expect to see in the future. Thus, themes collide, as 'Entertainment Architecture' is projected back on itself. What you see might be what you see, but it's not necessarily what you thought you would get.