Mehrfach verblichen

Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili’s images conjure depth from the flat surface of photography

Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili’s images conjure depth from the flat surface of photography

The Yellow Wallpaper is a haunting tale. In Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s 1892 short story, a woman whose family believes she is mentally unstable is confined to a single room, where she slowly descends into madness. The floor of the room ‘is scratched and gouged and splintered’ but it is the curiously patterned yellow wallpaper that plagues her. What starts out as a surface full of ‘dim shapes’ in the character’s eyes becomes chaotic and vivid. At first she sees fungus, then toadstools, and eventually, underneath the surface pattern, she begins to see a woman trapped behind bars: ‘But in the places where it isn’t faded, where the sun is just so – I can see a strange, provoking, formless sort of figure, that seems to skulk about behind that silly and conspicuous front design.’

Many of Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili’s photographs have images similarly ‘skulking’ behind other patterns or designs. Not coincidentally the press release for the Berlin-based artist’s 2012 show Tunnel, together with Benedicte Gyldenstierne Sehested at Ancient & Modern in London, consisted simply of an excerpt from The Yellow Wallpaper. The artists’ work, including an image by Alexi-Meskhishvili entitled Yellow Wallpaper (2012), of a faded flower-patterned paper slouching against a window, was installed on walls painted a sickly bright yellow. Like in Perkins Gilman’s story each of Alexi-Meskhishvili’s images concerns a flat, printed surface that takes on a life and depth of its own. Yet somehow we know this can’t be possible, since a photograph, like wallpaper, is just a flat, two-dimensional surface. Isn’t it?

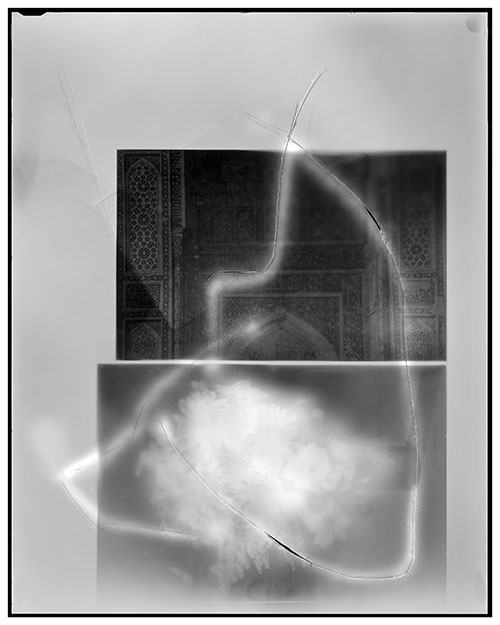

Alexi-Meskhishvili is part of a lineage of photographers who exploit the photograph’s three-dimensional or sculptural characteristics as much as its superficial, two-dimensional ones. Photographs become objects from which to create new photographs. Like other artists of her generation – among them Walead Beshty, Liz Deschenes, Sam Falls, Eileen Quinlan and Mariah Robertson – she’s also pursuing the idea of what it could mean for a photograph to be non-representational, even abstract. Her works employ tactile processes more associated with painting, drawing or sculpture. Traces of her hand remain: slivers, razored edges, overlapping layers, gaping holes, redacted faces, glare and lens flares appear. Like Perkins Gilman’s wallpaper, despite the layers we see within them, they are still flat surfaces. The end result, for Alexi-Meskhishvili, is always what she calls ‘a good print’.

Alexi-Meskhishvili is a graduate of the photography programme at Bard College in New York, under director Stephen Shore, where students are urged to learn traditional analogue techniques, to shoot with large format cameras and to perfect the art of making black and white as well as colour prints. Ironically (or not) this mastery of the fundamentals of the medium has allowed many Bard alumni to successfully depart from them, to great effect. Bard graduates like Beshty, Lucas Blalock, Daniel Gordon, and Alexi-Meskhishvili have all worked to manipulate photographic prints and negatives, collage them with other media, or discard the use of the camera entirely.

It’s a testament to her education that Alexi-Meskhishvili continued to use a 35mm camera after graduating, and still hews closely to analogue processes. Her blog, which she maintained between 2009 and 2013, was a repository for her 35mm images, fragments of which also reappear in her works. These photographs, some taken on her summer visits to her native Georgia, form a sort of travelogue or visual diary: street views, shop windows, gardens and foliage, buildings and metro stations, but also friends and relatives. Sometimes a misplaced fingertip in front of the lens muffles the edges of the frame, or the sun’s glare is reflected off a window. In an entry from August 2012, a woman in a canary yellow dress in what looks like an eastern European suburb stands near a canary yellow car. The caption reads ‘she came out of the yellow car’.

Alexi-Meskhishvili moved to Berlin in 2006, where she began developing her aesthetic of experimental combinations of digital and analogue techniques, revealed in her collaborative publication with Andro Wekua, Anywhere Anyhow (2009), and later in Ere Is My Head, the publication accompanying her solo show at the Eighth Veil in Los Angeles in 2010. Ere Is My Head is a series that ranges from found photographs to collages that collide two distinct places and times, to nearly abstract swathes of colour made without a camera. In several of the photographs, she manually subtracted parts of the negative with an X-Acto knife, sacrificing originals that can never be recomposed. Ere Is My Head (sky) (2001/08/09) reveals a gaping hole, roughly the shape of a human head. The series also examines the effects of light on the objects before the lens: what looks like the refraction of a sunbeam reveals fingerprints and smudges on panes of a mirror in flat Death / Sheet film (1), or the angle of the sun that makes a framed photograph of a girl cast a long shadow on a sun-drenched white wall in Box (2008). In Keti (2009) she re-photographs a photo from a family album but places it askew in the new image. On the opposite page, in flat Death / Sheet film (3) (2009), it’s as if we see the snapshot of Keti again, but we are looking straight at its edge, so it forms just a blurred smudge on a white ground. The juxtaposition is a reminder of the two-dimensionality of a photograph (its ‘flat Death’, as Roland Barthes called it in his seminal 1980 book Camera Lucida), but also the three-dimensionality of the photograph-as-object.

When I visited Alexi-Meskhishvili in her studio recently, there were a few visible traces from German Flowers, her first solo show at Micky Schubert in Berlin last autumn. Gold foil, reflectors and gels, cheap flower print wrapping paper, plastic and fabric flowers, torn posters, and shelves full of archival boxes of analogue prints cluttered the space. Swans drifted by outside the window, which is near eye level with the river Spree – a sensation the artist describes as ‘like being on a boat’. The walls, perhaps not incidentally, were painted a pale yellow.

German Flowers was an exhibition that revealed a cohesive aesthetic in full bloom. In these works, images float behind or in front of other images. They are ethereal and ephemeral, but not slight. Though the series has vast variations in the sizes and styles of the prints, like a Roe Ethridge or Wolfgang Tillmans installation might, Alexi-Meskhishvili’s choices are somehow more eccentric, and the thread linking the images is harder to find. Despite the classical ‘flower’ theme, what ties them together is that the exaggeration of the susceptibility of negatives or the imperfections of the printing process becomes productive. It’s clear that Alexi-Meskhishvili is able to work with these and embrace the unforeseen results because she has a thorough technical knowledge of the processes by which they arise.

Many of her concerns and experiments are similar to the treatment of film by early experimental filmmakers, like Stan Brakhage, whose work cut against the grain of traditional ways of seeing and documenting. Brakhage famously scratched his own name and titles into the negative’s emulsions with a needle. He also created his 1963 camera-less short film Mothlight by pressing dried flower petals, dead leaves and moths’ wings between two pieces of translucent tape. In his influential 1963 publication Metaphors on Vision, Brakhage wrote, ‘Imagine an eye unruled by man-made laws of perspective, an eye unprejudiced by compositional logic, an eye which does not respond to the name of everything but which must know each object encountered in life through an adventure of perception’.

Alexi-Meskhishvili finds an affinity with Brakhage’s ideas about the fragility and malleability of the filmic negative itself. Several of her works in German Flowers reveal a layer of the process in which she scratched her own negatives, leaving different coloured marks depending on which side of the negative she scored. In Blue Flowers she created a photogram with a translucent plastic flowered gift bag that light filters through, then scratched the surface, then scanned the image and Photoshopped it to create a final print. Like Brakhage’s use of the translucency of found objects in Mothlight, Alexi-Meskhishvili created Blumen, Isa flower and Dark Palm by pressing flowers and their stems (both real and plastic) in a clear 8 × 10 negative holder and exposing them to light.

Rote Blumen is a concatenation of images: old and new, found and created, intentional and unintentional. Alexi-Meskhishvili placed red flower decals on the back of an old discarded large-scale print, then took it outside her studio to re-photograph it. The backlight casts a shadow of a gridded fence that shines through the print, as does the image on the reverse side, and a sliver of sunlight at the bottom of the image. White Flower, on the other hand, is created without a camera: it’s a scan of a seemingly perfect white bloom that she found in an advert for a spa, and Photoshopped to make even sharper. Wilfred flower is a ’found still life’ composed of a flowered book cover faded by sunlight, against which a plastic balloon had melted. Alexi-Meskhishvili placed the collage on cement and photographed it from overhead, so that the shadow of her long hair falling around her face becomes part of the visual collage. But the image that departs most obviously from the series is hmmmmm (2013). This black and white self-portrait shows the artist wearing a Lucy McKenzie-designed work coat and sitting atop the desk in her studio. But she has exaggerated her gaze to make herself cross-eyed – another kind of ‘mistake’ in the photographic process that’s nevertheless carefully controlled by the artist.

The confined woman hypnotized by The Yellow Wallpaper saw a ‘front pattern’ and ‘the woman behind’ who ‘shakes it’. Brakhage described the construction of the Prelude of his film Dog Star Man (1961) as superimposing two strips of film – ‘the chaos roll’ and ‘the structured roll’. You could say that Alexi-Meskhishvili’s images layer chaos and structure, too. There are moments of abstraction and opacity punctuated by clarity and pause. A photograph at every stage of its lifespan is inherently precious and fragile. Analogue printing is prone to variations and mistakes. Negatives and prints are susceptible to scratches, dust, fingerprints, grease, chemical drips and overexposure. But Alexi-Meskhishvili is not overly reverent or precious about them, knowing that there is no such thing as a ‘perfect’ print.

Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili is an artist who lives and works in Berlin. She has had solo shows at Kaufmann Repetto project room, Milan, and Micky Schubert, Berlin (both 2013).