Memories of a Meteorite

Fifty years ago, when a lump of extra-terrestrial iron fireballed towards Belfast, a stampede of street kids stopped in their tracks

Fifty years ago, when a lump of extra-terrestrial iron fireballed towards Belfast, a stampede of street kids stopped in their tracks

The thing about the meteor is that it takes on the suffix ‘–ite’ if it manages to survive arrival in our atmosphere and land in some solid form on Earth.

It’s almost as if, once the meteor enters our world, it must be assigned an ethnicity, an ideology, a religion – it becomes, alternatively, a Semite, a Thatcherite, an Israelite, an allegorite, a nationite, a gobshite – which is, of course, an absurd line of thought. Before our satellites pick up on its existence, the meteor is neither this thing nor that thing. After our satellites belatedly pick up on its existence, it remains fabulously impartial to the meaning we have bestowed upon it. It remains neither this thing, that thing nor the other thing. It’s not even a thing. Words, as usual, fail us. But a down-to-earth translation is needed, and here I insist upon collective responsibility. When I write lazily, presumptuously, of ‘our’ world, ‘our’ satellites, and wax on and off about the ‘we’ who conduct the bestowal, please don’t be succumbing to my generalizing delusions if you happened to observe one of these hails of intergalactic light from your kitchen window off the Falls Road in Belfast, sitting up late one night struggling to complete a form for Universal Credit. Nor if you had your ears tensed towards the sky while smoking a cigarette from the cramped balcony of an apartment in the Paris banlieues. Anyway, what I’ve been meaning to say, is that a meteor, the meteor, any meteor, this meteor is, always was and always will be _____.

Which is no way to begin a thing you want someone, particularly, most manifestly you, to read. So, let me conduct a strategic, or at least a tactical, retreat. Artist and poet Noel Connor tells it better. He was playing at being the Portuguese striker Eusébio on the Koram Ring roundabout in the Andersonstown district of Belfast, ‘a concrete kerbed circle caked in flattened mud […] where four terraced streets converge […] scarred by all the passing feet’,when a meteorite scarred their sky, breaking up with the pressure, one part landing in a place called Bovedy in County Derry and another crashing through the roof a Royal Ulster Constabulary storage depot in Sprucefield, County Antrim. For Connor, that evening ‘is burned into memory, a stampede of street kids stopped in their tracks by that sudden roar and blaze of light’.1

That was on 25 April 1969. By August of that year, the Royal Ulster Constabulary had retrieved their heavy machine guns from their storage depots and used them to deadly effect. British soldiers had entered the streets of Belfast, sleeping and eating in the primary school in the middle of Bearnagh Drive where Connor lived. Families slept in other schools and parish halls or fled south to refugee camps and convents, some of their homes now but charred remains, standing as glaring warnings to those who would seek, disobediently but peacefully, to change the nature of the things that held them in a form of static malnourished melancholy.

On the night of the meteorite, 49 of Connor’s immediate relatives lived within a mile or two of his family home. As the conflict on the streets intensified, that number diminished to nine; his brothers and sisters moved their families out of the city, eventually settling in England, north America and Australia.

Decades later, when Connor returned to the meteorite as a topic of investigation for his work and began asking around, wishing to share notes and memories, not one of his family and friends could recall the event; as if, in his words, ‘the subsequent decades of violence and unrest had extinguished the memory of that extraordinary spectacle’.2

Today, the shortcomings of collective memory are often attributed, like much else, to the damaging influence of the internet age and social media. But historical amnesia has deeper roots. Sometimes, it has needed a helping hand – such as in 2003, when a ‘United Nations-blue’ curtain was draped over a tapestry copy of Pablo Picasso’s unflinching depiction of war, Guernica (1937), at the UN Headquarters, so that Colin Powell could advocate the immolation of Iraq without fear that those in front of him would be moved to uncomfortably shifting in their seats. The conception of radically altered futures is equally hard to fathom for some and judged suspect by others. That things as they are simply cannot hold – must fold, in fact, to give way to something more porous – can be as unsettling as the tearing apart of the sky by a lump of extra-terrestrial iron that has travelled eons to get here.

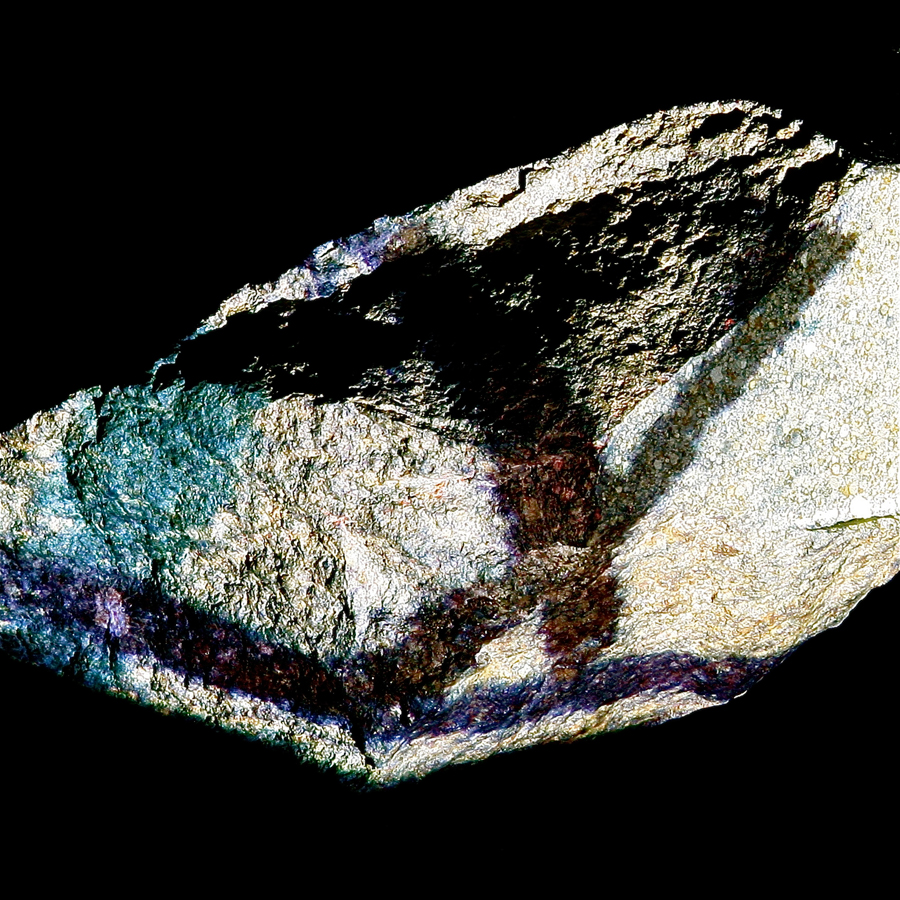

The routine of a school day can act as comfort blanket against such uncalled-for happenings, although more for those in charge than for the children themselves. Here is Connor on the roll call at De La Salle boys school the day of the unannounced arrival: ‘Brother Stephen registers only the present, knows nothing of the future […] fireballing towards Belfast, which tonight will tear my childhood sky apart.'3 More than 30 years later, Connor stumbled upon Brother Stephen’s registers as he wandered La Salle’s derelict corridors, hulks of concrete and red brick, in the days before its demolition. In the early 1970s, Connor left for England – where he set himself up as a teacher, an artist and a poet – returning only intermittently to Belfast to make a few pounds working on building sites. Belfast, like the meteorite, was always on his mind though and, on one trip home, he stumbled upon the rock at the Armagh Planetarium, eventually gaining permission to trace upon it the ‘Xs’ of school attendance from 25 April 1969.

The spring of the meteorite gave way to a summer of violence: an irreparable rupture between the spliced, severed outcomes of an old world (much like the wires in your common plug after a house fire) and the moans of a new one, or new ones (or three or five or one trillion). A bastard birth, if you will – if you won’t, so be it; an incitement to the Herods of the age to do their bloody worst. Which, bless them, they did, and do, with the utmost vigour.

'The Bilko Rosary' (2016) is Connor’s paean to the dying embers of that world: ‘Our friends would never call at that time after tea, terrified they might be brought inside and made to wait, made to kneel with us elbows resting on the dented seats of the four dining chairs, or line awkwardly, shoulder to shoulder along the front of the low settee, forced to join us in our evening prayers. We could hear them playing in the street, the Gilmores, Bannans and McCanns, while our mother told us once again: “The family that prays together, stays together”.’

By the time my grandmother, Connor’s sister, was attempting the rosary in the same house with my father and his siblings only a few short years later, it failed drastically – the nervous energy being just too much, the football on the television an irresistible draw, the gun battles in the street a stern pitter-patter laugh at her piety. The joyful ‘shout in the street’ that was James Joyce’s urban god in Ulysses (1918) had become a word of warning, a threat to desist or suffer the consequences, a tortured scream, a sound of nails and screws, plastic and lead bouncing off stone and burrowing into flesh.

On the night of the football match on Koram Ring, a woman in the North Down coastal town of Bangor was taping the songs of birds in her garden, a recording of which still exists. The chirrups and tweets and peeps of what may be swallows, house martins, willow warblers, spotted flycatchers or cuckoos are gradually subsumed by the steady rush of what could be a large car approaching at speed along a deserted motorway. Then the birds are silenced by the crunch. In the distance, a nervous dog barks.

Main image: Patrick Cunningham’s attendance mark from the original register of La Salle School Belfast, for 25 April 1969, projected on to the Bovedy meteorite. Courtesy: Noel Connor

Noel Connor’s ‘The Bovedy Illuminations’ will be shown at Séamus Heaney Homeplace, Bellaghy, County Derry, in October 2019.

1. Noel Connor, 'The Bovedy', The Bovedy Illuminations, Marketplace Theatre, Armagh, 2019

2. Noel Connor, 'Introduction', The Bovedy Illuminations, Marketplace Theatre, Armagh, 2019

3. Noel Connor, 'The Bovedy', The Bovedy Illuminations, Marketplace Theatre, Armagh, 2019