Musée Imaginaire

Skimmed over the walls of the new Museum of Installation, the plaster is bare pink, its smooth sheen full of promise. Behind an innocuous shopfront on Deptford High Street, a rigorous refurbishment has gutted an old store of its innards. The museum is a freshly scrubbed newborn entity.

The inaugural show, 'Musée Imaginaire', is in two parts, after which the museum will close for the next phase of development. In this first part, the installations meld with the developing state of the building. Upon entering, the visitor encounters Michael Petry's vertical array of headlamps. This apparently confounded project is entitled The Wormhole (maquette for an unrealisable installation) (1996-7). The light cast from these columns of brutish bulbs has created an unexpectedly delicate interlacing of penumbra on the adjacent wall. Yet on the opening night when the window blinds were raised, the light apparently shone forth across the High Street, stopping passers by in their tracks.

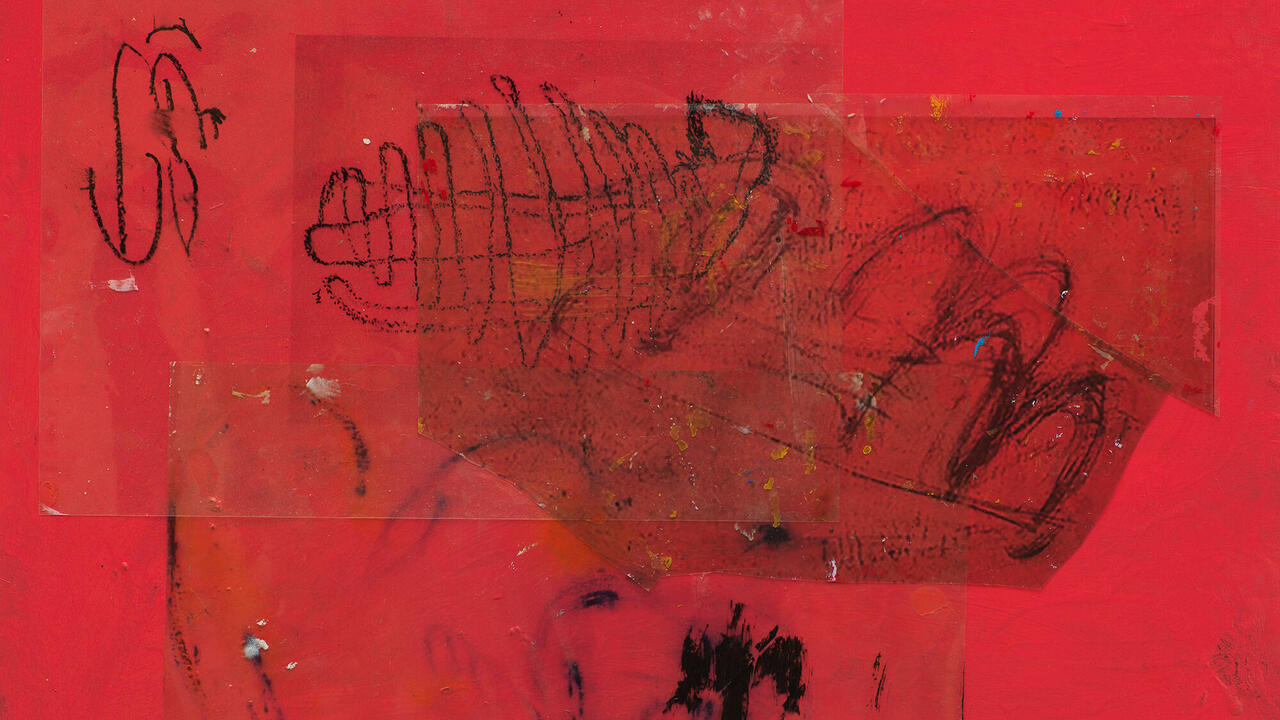

Stretched along the opposing pink wall, furry rectangles are regularly spaced. In Terry Smith's Exhibit (1997), pencil-written texts divulge that the 'fur' is mainly the dead skin of curators in the form of dust emptied from the vacuums of gallery cleaners (including those of the Royal Academy and Tate Gallery). Is this a form of Salon des Refusés? In Steve Dutton and Percy Peacock's piece, entitled Apocatropes (1997), further remains are visible: in a large photograph of a studio whose space is punctuated by scattered evidence of artistic activity, and in an accompanying video which shows a series of accretions of things. A sign declaring 'NIGHT OUTSIDE NOW' indicates that scenes are being set. Furniture for the little people is scattered amongst a series of propped-up stirling board rectangles.

An Alice in Wonderland change in scale is effected in the small chamber behind Dutton and Peacock's photograph. A resplendent chessboard floor, the only remaining feature in the otherwise stripped-out space, contains Baroque (1997): three preened and plump pieces by Rosemarie McGoldrick. Lavishly covered with damask, these upholsteries have been executed with finesse. A dominating black column rises from four spindly legs. Two conceits, a murrey-winged folly, and a drawing-room-yellow, curlicue caper bloom unabashedly from the walls.

Next door, Renato Niemis' construction Two in One Slice (1997) is a thin diagonal swathe of interior cladding. This loop links two glazed images one a diagram of a gun annotated with names, the other a photograph of a tank being regarded by three children in shorts. Strangely, the names on the diagram seem, intrinsically, to be those of children. But of course, Kevin and Sophie will not always be children unless a gun intervenes. Descending the stairs into darkness, the visitor encounters a blue light pulsating ahead. Inside this subterrestrial cell, Waiting (1997), by John Bartholomew embodies five large hanging sacs. These capsule forms emulate respiration, asynchronously inflating and deflating. Within their midst, there is a sensation of pressure: these glowing lungs seem to expand by inhalation of your exhalation. Their artificial pump ticks and hisses in the corner. Negotiating the confines of the cellar, a dim projection, Contrary to your way of looking on (1996-7), by David Wilkinson is encountered. Water swirls and eddies, the spume slowly defining the current and registering this filmic image in the gloom. Nightmarishly, the water has no discernible direction. Its projected surface threatens and suffocates, compounded by the stifling, clandestine blackness.

Emerging into what is now bright light, it is possible to see the way to Nathanial Stewart's installation, Where did your love go? (1997). Tucked behind a pillar and under the stair, a muslin gauze forms a translucent screen. Beyond is a low, vaulted chamber serendipitously lit from a recess in the ceiling. Light catches on a puddle on the floor. Faint aromas of soapy products waft by: there are hints of coconut and April freshness. Stewart has scrubbed this space assiduously making it clean and presentable. As a barrier, the screen preserves its newly refined state.

Back upstairs, looking at the revealed idiosyncracies of the building as the sounds of Deptford filter inside, it occurs to me that this venture is not an imposition, but an addition. Rather than asserting white cube tendancies, the Museum of Installation has created an anomalous identity.