Never Forget

Art's response, then and now, to World War I

Art's response, then and now, to World War I

In the early summer of 1914, the avant-garde art scene in London was in full swing. At the end of June, Wyndham Lewis published BLAST, the official journal of his newly formed art movement, Vorticism. The magazine became notorious for blasting Britain for its dismal climate, Victorianism and politeness: ‘BLAST HUMOUR Quack ENGLISH drug for stupidity and sleepiness.’ Blasts against parochialism, snobbery and aestheticism were offset by blessings, including, first of all, for British seafaring, seafarers and all ports: ‘BLESS these MACHINES that work the little boats across the clean liquid space, in beelines,’ wrote Lewis. Just one month later, World War I broke out. The Vorticists held their one and only exhibition in June 1915, declaring themselves ‘necessary to this country’ and, by implication, to the war effort. Edward Wadsworth showed a large, dramatic geometric woodcut celebrating the port of Rotterdam. When the second and last issue of BLAST appeared in July 1915 as a ‘War Number’, the belligerence of Vorticism had been out-classed by the scale of the war taking place. The editorial declared: ‘BLAST finds itself surrounded by a multitude of other Blasts of all sizes and descriptions.’ The issue included a Vortex manifesto, written from the trenches by the sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska claiming ‘this war is a great remedy’ that ‘kills arrogance, self-esteem, pride’. His message from the front appeared alongside his death notice: mort pour la Patrie at Neuville-Saint-Vaast on 5 June 1915. Gaudier-Brzeska was the avant-garde’s first casualty. By the end of that year, most of the radical artists had disappeared from London, the majority having volunteered for war service. In early 1916, Lewis himself signed up for the Royal Artillery and Wadsworth joined the navy.

It has often been said that World War I put an end to the avant-garde, though the story is more complex than this. Certainly, when it ended, painters and sculptors who had seen active service returned to an altered world with different politics, although — uniquely in Europe — by 1918, many of them had found official employment as war artists. Before 1914, the art of Vorticism had celebrated hard machine forms, industrialization and the vigour of mechanized energy. It shared this embrace of the machine age with other European art movements, including Italian Futurism. World War I was the first global industrialized conflict. It was fought with heavy armament, including the newly invented tank, and its enormous armies were delivered to the front line using systems and railway timetables developed to supply modern cities. These armies were slaughtered on an unprecedented scale.

However, the Vorticists’ contribution to the war effort would not be as mercenaries of the first machine age. Instead, the geometries of the movement’s visual style uncannily predicted dazzle painting, invented to protect British ships being torpedoed in the Atlantic by German U-boats.

Dazzle painting is credited to the marine artist Norman Wilkinson. It involved camouflaging ships with geometric patterns in contrasting colours, not in order to make the vessel invisible, but to confuse an operator sighting a target through a periscope about a ship’s direction and speed. It was evidently effective and a unit based at London’s Royal Academy designed individual patterns for particular ships. Wadsworth was transferred to oversee the application of designs in Liverpool and Bristol. In 1918, he was commissioned as an official war artist for Canada, and produced a monumental canvas of a ship in a Liverpool dry dock being dazzle-painted and numerous woodcuts of dazzle-decorated ships in ports. What the woodcuts don’t acknowledge, and the contemporary photographic records of the dazzle ship campaign don’t show, is how colourful the original designs were.

2014 marks the centenary of the outbreak of war but, perhaps more crucially, it’s also the year in which the Great War can be said to have finally passed out of living memory. As part of widespread acts of remembrance and documentation, an independent, ongoing programme, ‘14–18 NOW’, hosted by London’s Imperial War Museum, has commissioned large-scale public works by international artists. One commission has been the creation of dazzle designs for two ships in Liverpool and London. The Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz Diez, well known for his Kinetic and Op-Art work of the 1960s, has designed a new art work to ‘dazzle’ the pilot ship Edmund Gardner in a dry dock next to Liverpool’s Albert Dock. As the artist has remarked, where World War I dazzle painting was a defensive measure, he has created his work in order to reflect the energy and life of the city of Liverpool. It is part of the project ‘Monuments from the Future’, a collaboration between the Liverpool Biennial and Tate Liverpool, which aims to imagine new futures from the city’s industrial archaeology. Perhaps visualizing regeneration is one way to understand that World War I now occupies international memories in a different way to the past.

2014 marks the centenary of World War I but, perhaps more crucially, it's also the year in which the Great War can be said to have finally passed out of living memory.

To discuss the Great War as an industrialized conflict rooted in the same accelerating pace of modernity that gave rise to art movements such as Vorticism is to understand it as a rational and scientific endeavour. But the dominant image of this war, particularly of where it was fought in France and Belgium, is mud. Because it was largely siege warfare with opposing armies bogged down in trenches — often for years, and pounded with heavy armament almost daily — the terrain where it was fought became a quagmire. Mud is muck, a scatalogical, formless morass which sucks at the body it threatens to suffocate. The mud of the western front was not only contaminated with unexploded ordnance, shrapnel and rusted shards of barbed wire, but also with decomposing bodies and body parts that had been blown up and dismembered in the endless bombardments; it was a primordial slime that made a body’s boundaries porous and dissolved an individual’s sense of self. Frederick Varley’s painting T? (1917–19) was part of the work he undertook as an official war artist for Canada. Well known as a member of the Group of Seven, who forged a new sense of Canadian identity through landscape painting, Varley suggests a perversion of the pastoral possibilities of landscape into a ‘polluted’ and hopeless vision of death. Graves marked with white crosses are swamped with pools of stagnant water; army grave-diggers stand sentinel to a cart piled with khaki-clad bodies and jumbled body parts, the whole image stained with murky tones. When he was visiting the front as an artist, Varley wrote to his wife that, although it might be healthier to forget, it was impossible to do so.

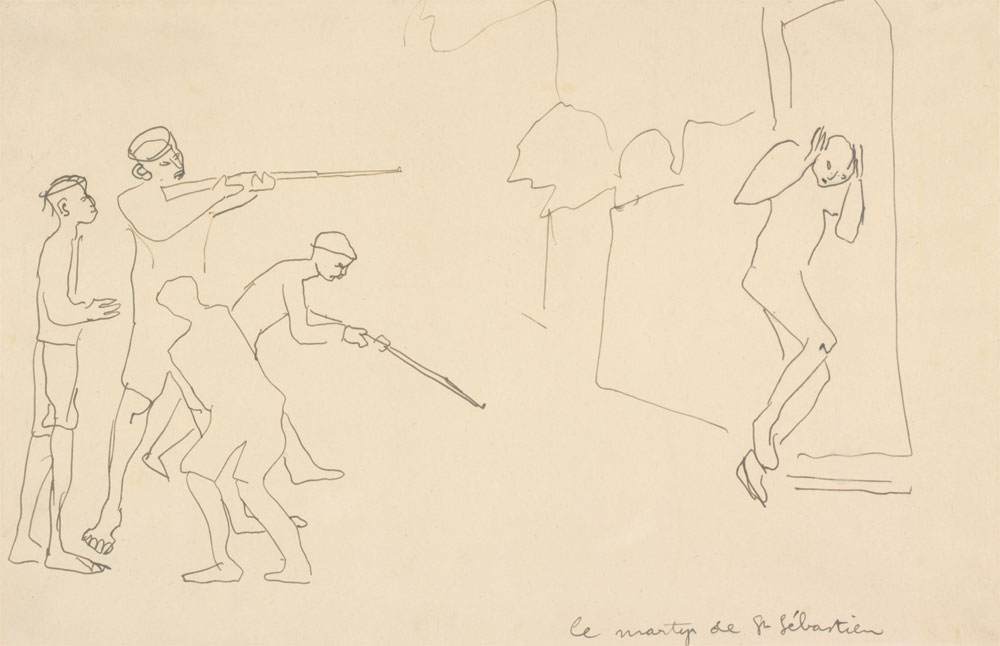

A small sketch that Gaudier-Brezska drew in 1914, titled Le Martyr de St Sébastien (The Martyrdom of St Sebastian), serves as a coda to reflecting on how art responded to World War I, and how it might continue to do so 100 years later. A slight figure flinches before a firing squad of four men, possibly soldiers; the isolation and vulnerability of the victim is poignantly delineated. One of ‘14–18 NOW’s commissions is a series of photographs, ‘Shot at Dawn’, by Chloe Dewe Mathews taken at sites where Belgian, British and French soldiers were shot, usually at daybreak, for cowardice and desertion. When it comes to remembering World War I there are things it is impossible to forget but also events and victims that have never been fully acknowledged. The task of remembering — and remaking memories — of the Great War is one that art in the 21st century might begin to undertake.