Nicole Eisenman’s Literary Inclinations

Novelist Isabel Waidner explores the artist’s keen interest in writing and books

Novelist Isabel Waidner explores the artist’s keen interest in writing and books

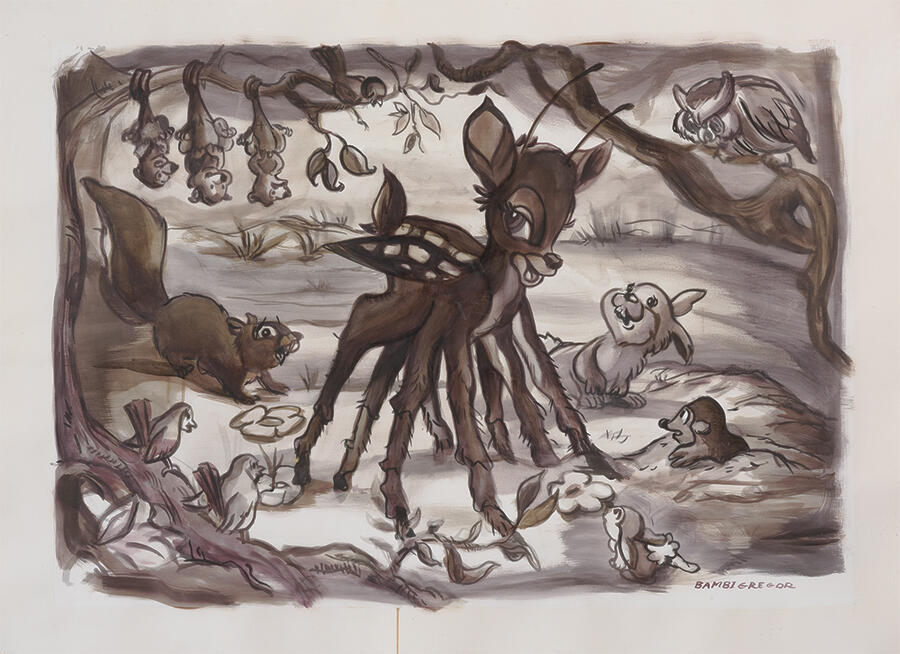

In the centre of the drawing, brown ink on paper, Bambi is batting his lashes and smiling disarmingly. When I say Bambi I mean Bambi, but not as we know him: on top of his famously unsteady legs, he has four spider’s legs – a grand total of eight. He is trying out his new set of insect wings, preparing for take-off perhaps. Could be that he can’t wait to get away from his little friends, including Thumper and Friend Owl, who, surrounding him, watch in consternation. Something is wrong with him, they suspect, as in, very wrong.

The US painter and sculptor Nicole Eisenman – whose first major UK survey show, ‘What Happened’, opens this month at Whitechapel Gallery – called this drawing Bambi Gregor (1993). The title is an allusion to Gregor Samsa, protagonist of Franz Kafka’s short story ‘The Metamorphosis’ (1915), who wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into an ungeheueres Ungeziefer – a monstrous vermin, gigantic insect or cockroach, depending on translation. Bambi Gregor is an early-ish and, in the context of Eisenman’s hugely impressive catalogue, arguably minor work. However, its recent appearance on the cover of Honey Mine: Collected Stories (2021), a compilation of new and out-of-print fictions by lesbian New Narrative-affiliate writer Camille Roy, published by New York-based Nightboat Books, brought it into the present for many – especially readers of innovative fiction. During that same summer, as I was writing Corey Fah Does Social Mobility (2023), I kept a copy of Honey Mine on my desk, and its cover star became a jumping-off point for me to write my own Kafkaesque, Eisenman-esque protagonist – more of that later.

Eisenman is an effortlessly referential painter who draws on source material as diverse as renaissance art, 1930s socialist murals and cartoons like Bambi (1942). Another example is Alice in Wonderland (1996), a painting which shows young Alice going down on Wonder Woman – or, rather, up, as the stars-and-stripes-clad heroine stands over the girl, legs apart, in victory pose. Much has been made of the influence of pop culture, US politics and art history on Eisenman’s work – arguably less of the impact of literature. Guy Reading The Stranger (2011), for example, depicts a person reading Albert Camus’s 1942 novel in front of a bookshelf sustaining a ‘best-of’ of European philosophy, including volumes by Hannah Arendt, Roland Barthes and Martin Heidegger. The Triumph of Poverty (2009), a large-scale figurative painting more typical of Eisenman’s later work, features disenfranchised disparates from various historical periods – including an orphan with a begging bowl who might be Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1837) – gathered around a broken-down car. Another Green World (2015) references Brian Eno’s eponymous 1975 album, but also, as Eileen Myles observed in a 2016 article for frieze, the critic Northrop Frye, ‘who contended that, in Shakespeare’s work, the characters were always going off into the woods to find another mode of knowing and being – the green place’. Even Eisenman’s version of The Thing from Marvel’s Fantastic Four comic series (From Success to Obscurity, 2004) is reading something.

Incorporating their cultures and communities has long been integral to Eisenman’s practice. Paintings like Beer Garden with A.K. (2009) are populated by New York-based queer and trans contemporaries and friends, in this instance gathered around the artist A.K. Burns. It makes sense that Eisenman’s engagement with literature should not be limited to canonical works but should include, if not centre, contemporary literary communities and live literary production. ‘Eisenman loves literature and writers,’ Myles noted in frieze in relation to the painting Weeks on the Train (2015), in which the writer Laurie Weeks, laptop on lap, is reading and taking up space while travelling.

Writers, in turn, love Eisenman. In 1995, Myles invited the artist to contribute the cover to their collection Maxfield Parrish: Early & New Poems (1995): Eisenman created a striking, hilarious and threatening drawing of little flowers with unsuspecting faces building a large wooden sculpture of an uber-flower. More recently, Eisenman provided the cover art for Myles’s momentous 700-page anthology, Pathetic Literature (2022), which sets out to rehabilitate pathetic-ness in diverse forms of writing spanning centuries. In it, a figure in white holds a black cat as far away from their body as possible, another sleeps in a demented sun lounger, while yet another smokes a rollie – all in a landscape where nothing but a leafless excuse for a tree eases the beige. ‘I like seeing my work on the cover of poetry books!’ Eisenman said in a conversation with writers erica kaufman and Matt Longabucco published earlier this year in Ursula magazine. My point is: the literature–art traffic goes both ways.

My ambition for Corey Fah Does Social Mobility was to examine and challenge conservative notions of social mobility, which, especially in fiction, are often related as simplistic triumph-over-tragedy narratives, or connected to mythologies around merit. I use the example of a disadvantaged writer, Corey Fah, winning a prize (not unlike myself) to make the case that it might not be quite so straightforward: parachuted into unfamiliar contexts of social power and opportunity as a result of their win, Fah has to contend with their difference and their messy past catching up with them. At one point during the writing process, I was searching for a historical or fictional figure through which to write Fah’s complex past – a container capable of holding trauma (the death of Bambi’s mother, of course, being the first encounter with the concept of parental loss for many of us), as well as otherness, that is, queerness, insect legs and all. Bambi Gregor, as featured on my copy of Honey Mine, was just that.

In a sense, Roy’s fictions are less literally connected to Bambi Gregor than is Corey Fah Does Social Mobility – no spider-Bambi cameo far and wide in Honey Mine. In another sense, the connection is far more, I want to say, personal: Roy – like Eisenman, like Myles, like Weeks – has been part of a US lesbian counterculture for decades. They may all be friends. Whereas I, a British-by-naturalization, working-class novelist, a decade Eisenman’s junior, come at the work sideways.

In the writing process – as, I imagine, in the process of painting – if it is going well, preliminary influences coalesce, become transformed and ultimately emerge as something surprising and original. Skeletally propped up by now fairly obscured, half-forgotten source material, characters take on a life of their own. With eight eyes and a hidden drinking-straw-like-mouth, my character, Bambi Pavok (pavok is similar to the Czech word for ‘spider’) is related to, but divergent from, Eisenman’s Disney perversion in terms of physicality. Beyond that, Bambi Pavok graduated from his 2D cartoonish status, acquiring psychological layers, emotional dimensions, a backstory and a British accent, so to speak. To get to this point, it’s perhaps simplistic to say that I brought Bambi Gregor in conversation with cultural references much closer to home, and with literary traditions that I myself write in and see myself in relation to. For example, I recruited autobiographical detail pertaining to British playwright Joe Orton into the novel alongside my own, which allowed me to think through and write about gay, working-class authors winning literary prizes historically and in the present – a rarity to this day. I also mobilized existing similarities between Orton’s and my writing styles, putting to work irreverence, morbid humour and outsider perspective to aim to produce not just a formally interesting novel, but a critique of class inequality. What happens when Fah, Bambi Pavok and an Orton-inspired character meet in the novel? No spoilers, but imagine unspeakable scenes.

The cover of Corey Fah Does Social Mobility features UK-based artist Linda Stupart’s interpretation of Bambi Pavok. (Stupart made the original cover art for my second novel, We Are Made of Diamond Stuff, which was first published by Manchester-based micro-press Dostoyevsky Wannabe in 2019. I consider Stupart part of my own extended community of contemporaries, and I have been in conversation with their work for many years.) A collage of a naturalistic young deer stands confidently in sepia heathland which, with its low bushes and industries in the near distance, looks distinctly – mildly depressingly – British. Multiple insect legs are emerging from under his body, and his eyes – just two of them – are bright-red flowers. A collection of discarded trophies has been dumped at his feet, some of which – with their bulging veins or signs of knotweed infestation – seem positively alive, or overtaken by something alive. A cluster of textured pink and white bunny stickers represent Fumper, another character from the novel, or Thumper from Disney’s Bambi, or Eisenman’s Bambi Gregor – who knows anymore? Creeping out from under the torn edges of Stupart’s image, something more sinister is hinted at – more rampant insect legs upon which the entire fantasy unstably is built. The iteration of Bambi that appears on the finalized Corey Fah Does Social Mobility jacket – designed by Jon Gray – is four- or five-times removed from Eisenman’s Bambi Gregor but, really, it is worlds away. It is its own thing entirely. No less funny than Eisenman’s version, or my fictional one – arguably even a touch next-level.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 238 with the headline ‘Gregor Samsa’s Bambi’

‘Nicole Eisenman: What Happened’ is on view at Whitechapel Gallery, London from 11 October until 14 January 2024

Main image: Nicole Eisenman, Another Green World, 2015, oil on canvas, 325 × 269 cm. Courtesy: © Nicole Eisenman and Hauser & Wirth