Pádraig Timoney

Pádraig Timoney's visual language privileges diversity over uniformity

Pádraig Timoney's visual language privileges diversity over uniformity

There is a still-life oil painting by Pádraig Timoney entitled Imagine this pumpkin is a superhuge concrete boat that has crashed into a small volcanic island in the bay of Naples, knocking the top off it and causing an eruption (2005). It is partly a picture of what its title says it is, and partly an incitement to imagine an entirely phantasmal cataclysmic scene beyond its modest dimensions and genre. The work suggested itself following the fortuitous sighting of a ship-shaped piece of orange pumpkin on a street stall. Besides the calamitous vegetable, the painting also depicts a studio view. Corners of other paintings intrude on the edges of the composition, and the arranged matter lies on a trestle-table marked with an artful rainbow of paint smears. The image is rendered dispassionately in a manner reminiscent of walking around your own room and optically assessing it like an intruder.

The painting has a droll appeal that comes from exaggerating the dimensions of the ordinary, courting the slightly paranoid limits of the associative power of images. Actually the painting isn’t visually typical of Timoney; in fact, none of his works is typical, because a dissident attachment to dissimilarity or to a certain amount of contrariness is one of the key premises of his praxis. To get an idea of the conceptual range of his work take, for example, another painting made around the same time, Dithyrmethitic Acid (2005), one of two works named after a compound that the artist dreamt could capture the essence of desire. Unfortunately the molecular formula escaped him when he woke up. The composition is something between a sign and a colour chart, with sequenced tones painted within a balsawood grid affixed to rose-tinted canvas. To an extent that you cannot calculate accurately enough, in creative endeavours second-guessing yourself is what makes things interesting. For Timoney this seems to mean that if he is going to make art, then he won’t conform to the common look-alike production mode. To prove his own point that everything is different but nothing has changed, when he was invited to a group show a few years ago in New York, he re-exhibited works made for his degree show over a decade previously.

Over the years Timoney has produced a few Conceptual travel pieces, including: drinking a pint of Guinness in his home town, Derry, without meeting anyone he knew there (Abortion, 1990); a pilgrimage to the Holy Land to gather cobwebs (Webs from Jerusalem, 1993); and a round trip to Hollywood to buy a blank VHS cassette tape (The Hunter Became the Hunted, 1996). Then there are also a number of off-the-cuff whimsical sculptures such as Taliban Beard Test (1997), a rough souvenir-like carved sculpture of a hand around a beard in response to reports that religious police in Afghanistan were assessing piety by the length of men’s beards, using their fists as a guide for a minimum length, and Just a Note (1998), an ironic rose-in-a-vase sculpture where the odorous bloom is formed with a red sock, a piece he made for a group exhibition in the stuffy quarters of a moored submarine. More recently another sculpture, Untitled (Gravel Dice) (2006), a two-cubic-metre pile of gravel with dice numbers sprayed on it, demonstrates how with ordinary material the number of possible outcomes can still approach something beyond the fathomable. Then there are also photographs, which are not limited to any particular genre either, such as Yes Meets No (1990–2006), a black and white print depicting a plaster sculpture of a tick and a cross that is dotted with a bright orange dust-cloud of gauche spots – intentional mistakes that, as the artist explains, ‘you can let yourself see or not’. Recently he also made an edition of home-made holographic text on metal plates saying Please Touch (2007), the artist achieved the optical effect using only scratch marks made with a compass. The works also have cast pewter fists protruding like door handles. There is a healthy dose of sardonic humour in all these works as well as an implicit reflection on what might be a worthy enough subject for art given the infinite permutations that arise from context and form.

As time has gone on, canvas painting, which was always there in Timoney’s work, seems to have assumed an increasingly central role. But true to an off-beat bunch of ideas, imaginative excursions and tangential interests, his paintings still refuse to resemble one another, putting a wilful spanner in the works of any notion of development or variation of a theme. Two of the results of this stubborn variance are that, even if familiar with some of his work, you can be forgiven for not recognizing a Timoney, and even worse, you might just have to look at each work on its own terms.

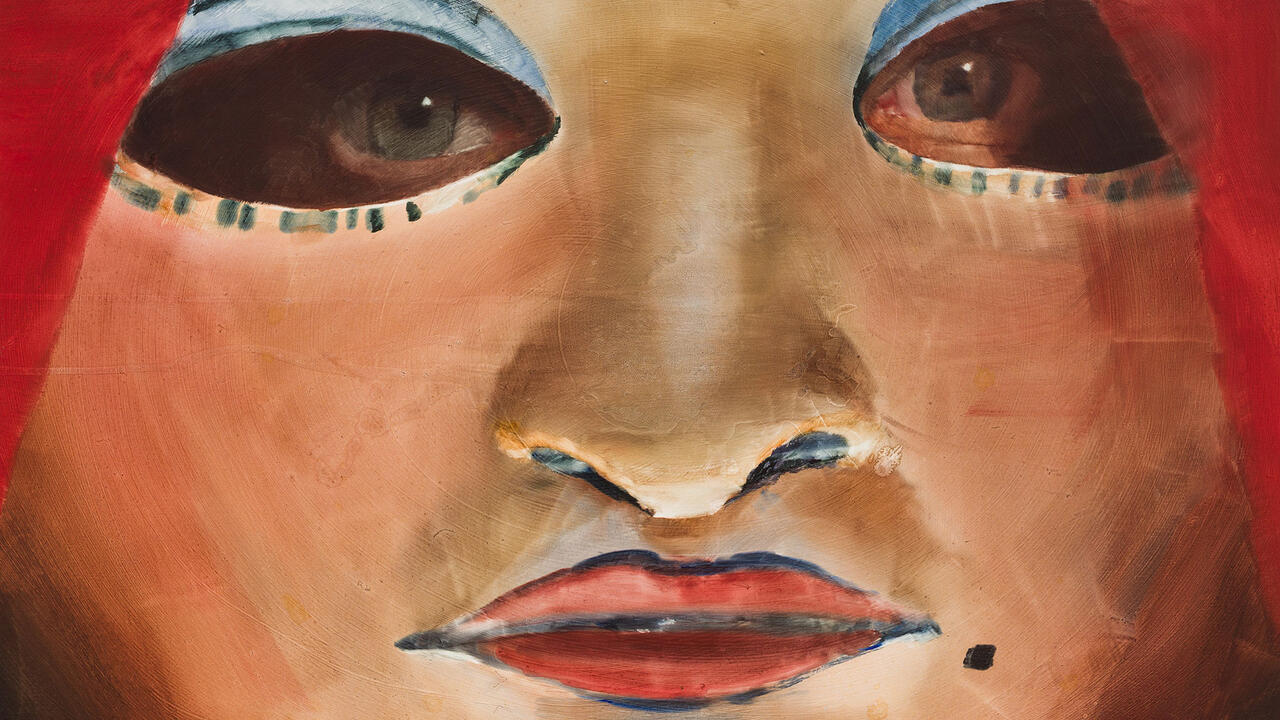

Thus Timoney’s solo exhibitions, such as ‘Museum Metropolitan’ (2007), at his Naples gallery Raucci/Santamaria, generally look like a collection of works by disparate creative souls, perhaps even from different periods and styles. He does what look like all-over abstract paintings with pleasant repetitive lines and shapes, such as the works from the ‘hedge’ series, including Privet Painting (1997), which plays on the shapes becoming leaves once you know the title; he does a brand of not-too-finicky Photorealism whose motifs include cricketers; and he does ambient-looking washes with rabbit-skin glue (a traditional canvas sizing material) – even though he is a vegetarian – where crystals form in watery outlines and flow on the surface, some of which feature ghostly female or demonic figures. Then there are still others with objects attached to them, such as Understudy (1999) – which has a metal outline of a laboratory rat ready for vivisection screwed on top of a canvas painted with abstract motifs that suggest the opening up of a geometric plane. He doesn’t even use his palette or sense of colour as an integrating force; it is equally unruly or anarchistic, in a way oriented more towards pleasure than good taste.

Timoney ignores the unwritten rule of commitment to a genre or method, or at least an underlying theme, as a sign of serious investment in one’s work – something that at its lowest common denominator gets expressed as the demand for a recognizable signature style (whether from the market or an uninspired art education). Fixing on one visual solution, using just one bag of technical tricks or way of holding and moving the brush, anyway seems at odds with the way we think and see and with a variegated experience of the world. If a body of work looks samey in reproduction, it’s probably because along the way it’s been cleaned up for easier consumption.

The closest thing to an analogy for Timoney’s visual language is probably something like cut-up poetry. Often the impetus for a new work may come from something striking if anecdotal. The crusty gold-sprayed 1950s’-like abstract composition Cruzzy Lotion – Liceolation (2004), for instance, was a response to catching lice on a cheap train in southern Italy. Most of his works have stories loosely attached to them that aren’t part of the work in their end-effect. For Timoney ‘there’s talking and there’s looking’; the individual works have to ‘hold their own’, forcing a situation of confrontation with a given support which he describes as pure ‘bloody-mindedness – when you think: it’s all going on there’. One way to achieve this can be seen in a few of his paintings where the artist has painted different images in dissimilar styles on top of each other, and then etched the surface using cleaning rags cut into abstract shapes and soaked in photographic developer, producing the visual equivalent of cacophony. In Turns on Top (2007), for instance, the image layers include a rendition of Nicolas Poussin’s gory, gut-wrenching The Martyrdom of St Erasmus (1628) and graffiti on a Neapolitan tube station wall. Scuán éirigí (2006) includes menacing birds and a bed with an art work lying on it awaiting collection. The Irish word éirigí loosely translates as ‘arise’, and the word scuán, which appears in the painting, is a Gaelicizaton of the English ‘go on’ – what the artist’s grandmother used to say when the chickens came into the kitchen.

These corroded, multi-level pictures, in which nothing is intact or pure, allow for all kinds of cross circuits and slippages between abstract and representational motifs, painted and photograph-based images. The artist’s chance discovery that photographic developer etches and eventually destroys oil paintings convinced him that ‘even in its chemistry photography has painting’s number’. Timoney is conscious of the danger that painting a photograph might just involve some kind of material aggrandizement, but also that paintings can do things photography can’t. A visit to the countryside in the south of France led to the landscape Introvertive Anhedonia (2006), painted from memory with a palette knife in the ‘Montmartre’ style, which has pigmented plaster casts of piles of sale tags attached to it and which winks at Paul Cézanne. The work was a response to the physical circumstances of the kind of landscape that inspired Cézanne, which Timoney felt hadn’t changed more than a century on and still demanded the kind of visual analysis that only painting can deliver. (Incidentally, ‘anhedonia’ is what you have when you don’t get pleasure out of the ‘simple’ things, such as food, sex or, for that matter, art.) This painting was included in a suite for his recent solo exhibition at Xavier Hufkens gallery, Brussels, which wasn’t so much ‘untitled’ as ‘not called anything’. It also included the pigment on canvas painting Sick Fig (2006), a sorry semi-denuded bush, and a number of cloudy, imperfect, home-made gold and silver mirrors whose scale corresponded to the canvas paintings in the exhibition. The artist thinks of the mirrors as ‘automatic portrait repetitors’ and likes the suggestion of alchemy or magic involved in their making.

Considering the visual pluralism (or skulduggery) of contemporary painting, which seems more often than not related to a kind of Postmodern Gothic – the subjective allowance of fragmentary image worlds – superficially at least Timoney’s work probably seems less out of place than it did a decade ago in London. In fact, his work probably has more to do with the project of a painter such as Michael Krebber, and however awkward a label it may seem – not least because of Conceptual artists’ general avoidance of painting – a variant of ‘Conceptual painting’. The painting Timetable Painting No. 3 (2002), for example, makes a simple but compelling observation about repetition and systems. This coloured broken grid takes as its model a school timetable – a place where traditionally unrelated subjects follow one another and are subsumed within a given system. In his work Timoney accepts the parameters while scheduling his own subjects and the form that the lessons might take at will, the only constant perhaps being the need to take the odd break in between.