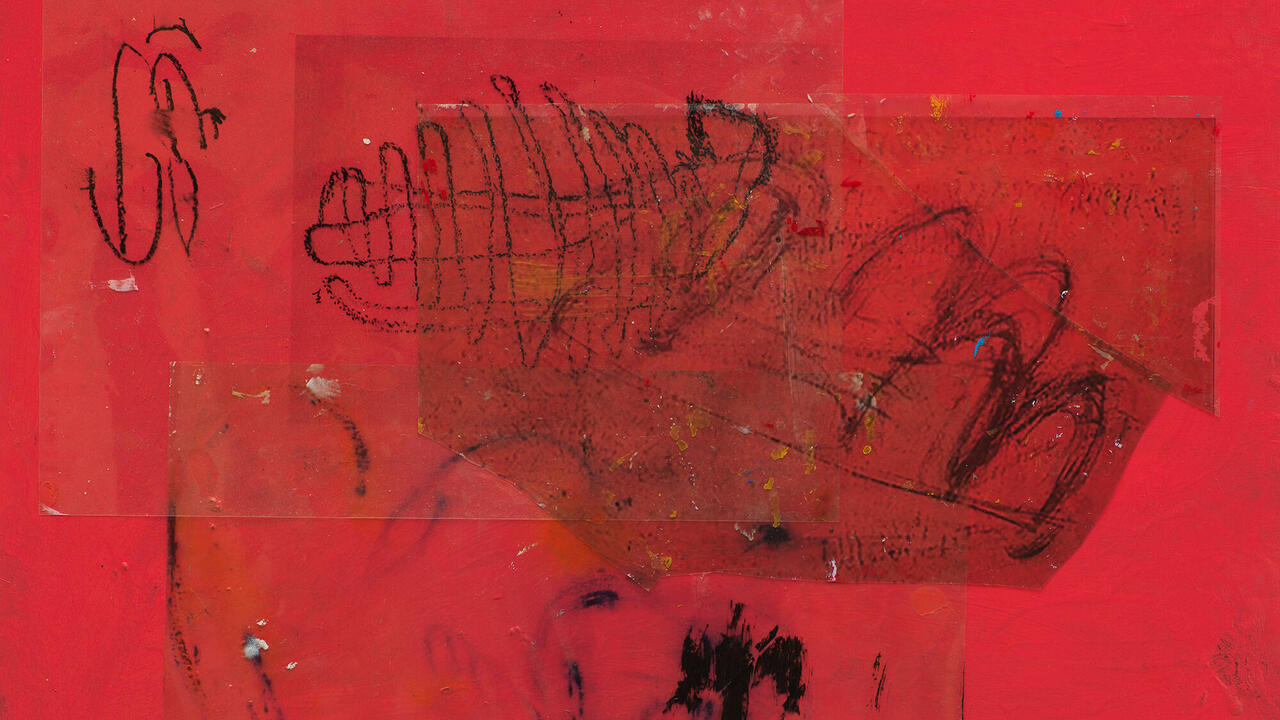

Paris, 1996

Patrick Faigenbaum

Patrick Faigenbaum

Last winter, I began to write about Patrick Faigenbaum's photo Paris, 1993 (1993). I taped it to the lamp near my desk where I could see it when I wrote. I look at it a lot, especially at the drawers and the way the boy's posture interlocks with the chair. It helps me think.

Sometimes a piece of art can animate relations between people, the way a new toy can make a family fight in an interesting way. I made a list of the people involved in creating and getting this image, finally, to me and then I asked each of them to 'tell me about the photo'.

Richard Flood was the gallery director at Barbara Gladstone gallery, where Collier saw the photo:

I have to tell you one thing: the copy I have of this photo is a xerox of a fax, and there are two radiant horizontal swipes obscuring the image. Does he have a Peter Pan collar? For some reason I remember him in a Peter Pan collar. In a funny sort of way, for me, this child was never a particular family's child, but a child out of a novel. The boy has an elegant remove from his situation in his attention toward the viewer, which is why people respond so strongly to it. There was never any question of figuring out who the photograph was of, it was just 'the child', looking at you. It was probably one of the most lingered-at images in the show. There was a great deal of interest in buying it.

Patrick is a flawless technician and that causes him a lot of strain. He's really peerless, but all that work happens out of my sight. Every time you ask him to go to a second print, it's almost horrifying. You feel bad that you've got another client.

I think the photo fits something that people cling to about childhood. The child is so right with himself and so clearly independent. At the same time he's controlled, under control. He looks like a very serious little boy who is giving nothing. But he's well socialised. The placement of the hands shows he's civilised. His feet don't quite touch the floor. The child appears to look and listen intently, which makes the viewer somewhat nostalgic for the perfect child, the fantasy child, the dream child.

The availability of him is all very seductive. The seduction is in the implication that the child would be interested in listening to you. Interested in being educated, in being alert for you. Part of it is the exactness of the pose. It looks like self-control. There are a number of Sargent paintings of children where they are really 'good scouts'. They let the artist do 'the best thing for them', which makes them idealisable by grown-ups. If a certain kind of luxurious passivity of intent is seductive, then this would be it.

One could ask these questions under totally different circumstances about Larry Clark's work, where the point of sale is really the vacuousness of the image. Someone made an interesting point about Larry's work, which in a way has gotten weaker. My friend said the problem for Larry began when he wanted to be the kid in the photograph. Desire is programmed into his photos. I don't think this happens with Patrick. This could be a photograph of a dog. It just happens to be a child. I could see many of these qualities we're describing being attributed to the promise of a good pet.

Barbara Gladstone is the gallery owner who set up the show:

Well, I have in a way the disadvantage of having had a long conversation with Patrick about the photo, so I know who the photo is of. Let me put it in front of me, so I can look at it while I'm talking. Okay, so when it arrived, it was the first time I'd had an exhibit about people who were known on a personal level to Patrick: the others were about the Italian families. These were about family, some about waitresses he knew, but this one about his nephew.

We got the prints, they arrived. They were fine. We suffered the usual last minute problems. The problem for Patrick is printing each copy. Each one takes so long. Once he's done the first one he dreads going in. He did have to re-do one. It wasn't his fault. He had to re-do it because the framer spilled something on it. It was horrible.

I remember thinking, when I saw the group of them, that Patrick had a different investment in them. The Italian photos were about people trapped in their surroundings. They were objects. It was easy to construct stories about the positions of the people, the weight of their rooms, the weight of history upon them. This group was far more the personality of the sitter being captured in the sitting. Everything was in service of the release of the personality.

This child, the nephew, had kind of come out of a Velázquez portrait, he looked like the Hapsburg children, complete with the dignity they are wrapped in, which is rare for a photograph of a child. This child is so clear and present and looks at you with, not an empty look, a deep look. He is still, only for the moment, and at any point he may break into a charming conversation.

What I quite love is this very simple piece of furniture on the left. It clearly places him in modern times. It's a machine-made cabinet. His face is not a 20th century face at all. The lower lip, I think is a Hapsburg lip, but in this case it doesn't look weak. The children in Velázquez have this kind of wisdom the adults don't, and I see it also here. I think it's possible to read eroticism into almost anything, but I don't think this photo reads in any paedophilic sense. Not that Patrick hasn't done that. I know of a portrait of one young girl who is sort of pubescent, sitting in her bedroom with no top on. And even though Patrick doesn't say so, that one has an eroticism. This photo, of the nephew, doesn't give an erotic sense to me. I find him just having trouble sitting still, anxious to get back to what he was doing. In that sense you could see him as trapped in the composition, which obviously took a long time to set up. The photo was not impromptu. None of them are.

Sylvian de Decker-Heftler represents Patrick Faigenbaum in France; she organised the photograph's delivery to Barbara:

The boy is not my favourite. A girl on the subway, a man in New York on a bench - these are stronger prints. There's a fabulous young girl in Portugal. These are works I would keep for myself. Robin, the boy's name is Robin, I won't say scares me. It is a bit dérangé, uh, disturbing to me. He is a bit soft, passive. He is not there. It is more about the personality of Robin, so I'm wondering who is this kid? I wonder what he's really like in fact. With Patrick, there's always something that's true.

Patrick took a picture of my children, it was very sweet, for a birthday surprise. They look extremely sad in the picture. It was taken at my mother's place. I think, in each picture, Patrick lets people be how they are. He has a way of working. When he is taking the picture he is extremely intense. There is something between him and the subject, which is very strong. He asked my children not to smile, not to speak. It's the opposite of reportage. You have to stay absolutely in the moment. He arranged everything with my mother, a complete surprise. He's like that. The package was very well made. It was a very, very sweet present.

So, why Robin is not my favourite? I am always very scared of the reason why people like a print. I'm afraid that with Robin it is for the wrong reason, okay? And I am always afraid of that. Because it is a young boy, because it could be put on the sexual tastes. And I know the print is not that. And I am nearly sure that Barbara Gladstone has sold it three time because of that. I know the work of Patrick and his work has nothing to do with homosexual tastes. You understand? Sometime you are wrong to not just let yourself go and like something which is good, but I'm 99% sure about the reason for it selling. You know, when you sell, you know so well the people, you know so well why people are buying, or why they are repulsed by something.

Patrick Faigenbaum is the photographer who took the picture:

The first print was at Barbara's show. After the show I did another one. It arrived from Europe, and I did a third one at the same time. Barbara sells the third one, but the customer, I say, has to wait, because I am doing the third print for a show in Israel. The print, it was marvellous. The print came back to me in February. I send it to New York, and until May, I have no news. Nothing. It arrived in February, and until May, nothing. And the print was at the gallery. Then one day I receive a phone call: it's the framer. He makes a spill of glue, on the print. A marvellous print. And I do another print. It's one of the most difficult to do.

So I say, okay, I will do another one. I did another one, which was very, very beautifully... different. It has to be, they are always different. I mean, it's like this, I work like that, I never do the same print. I never want to, there is no rule. I mean, it has to be good, nice, and I try to do it better and better. When it goes out from here it's perfect. Always I work on it until it is perfect. The print arrived, and the customer says 'it's very different from the one I saw, so I refuse it.' So I get a very small money from the insurance. It's not logical.

What I am very touched by in the picture, apart from the face and the hands and him, it is two things. It is these points of light, dot dot dot dot on the dresser, and that his feet don't touch the floor. For me it is so wonderful. You cannot do that, I mean you cannot... it just has to happen. It was very natural. I like so much that the feet don't touch floor, because he is too small.

When I take the photograph Robin was in himself, very much. His sister went away to another room. His sister is the child of my wife. When I met my wife, Robin's sister Lisa was 9 months. She is now 17. I am getting separated from my wife. It's better, we're still friends, better friends. So, Lisa's father, the first husband of my wife, ex-husband, married a second time. Lisa, I am like her second father. We are very close. But her father is her father. She goes to see him every second weekend. Her relations with my ex-wife and her father are very fine, so, good relation. So he married a second time and he had, from the second marriage, a boy, who is older, and a girl. The boy is he.

In New York, Barbara Gladstone asked me 'who is that?'. I say, it's my nephew, to simplify because it's too complicated to explain, I didn't want to get through the details. And he's like a nephew, or a cousin, I like him very much.

So he was nine years old, so I begin to do portraits of both of them, and after Lisa went in the other room with her father, her father wanted to speak with her, and with Chantal, my wife, so I close the door and I stay alone with him. And he didn't move. He was very quiet. I was very surprised. I stay alone with him. I had done some portraits with his sister by a round table, there was a nice light, and I continued the pictures with him close to the table. After, I turn around, I was almost finished with the work, and I decided to change place, so I took him to the chair, you see, and I said 'sit here.' (There remained a few pictures of film). He sat. It was like for him, he moved places, but for him it was like he didn't move. He was the same. I don't know, it was like hypnosis. He was not moving, not saying anything. He was so quiet, so in himself. It was like sleeping. It was not sleeping, but it was something incredible. So I move close to him and I find the frame, the right picture, every element was in the right place, the light and everything. I take the picture, finished, no film was left, but he stayed. I have to tell him 'Robin, thank you very much, you are free'. He realised after a few seconds, when I told him, after a few seconds, that it was finished. So he stand and was like a boy, like a child again. He came back to reality. But he left reality at the time of the picture. I spoke to him, during. You know in hypnosis, you say to the people 'put your arm here'. They do it without understanding, without answer.

Robin Mimoun is the boy in the photo:

I was not supposed to feel anything because it could have made me smile. I would look at Patrick. I'd look straight ahead. I can empty my mind when I'm bored. I can do that. Or, when I don't want to think about anything. What's most interesting about the picture is the one drawer that's pulled out. Patrick pulled it out. He wanted my pants pulled up a certain way, my socks.

I was lucky to have had this picture taken. This wouldn't have happened otherwise. If a picture of me is exhibited in a museum, it is thanks to Patrick. I posed, but it is the photo that people like. I'd like being famous, but that hasn't happened. It is Patrick who is famous.

It doesn't resemble me. I would not have dressed like that. It was two years ago, when I was eight. I remember I fell off my bike and almost got stung by nettles. My hair and my eyes look like me. What's not like me is the way I am sitting. It's like a child who is waiting, waiting for time to go by. He's bored. He's looking at where he is.

I don't remember the day. It was a long time ago, two years ago at Chantal's. Patrick moved the furniture when I got there. I had to sit on a chair. I had to remain sitting. He would look through the camera and then move things, like the drawers or the light. I was feeling good, but I was not supposed to show any feelings. I was thinking about not making any movement because it could ruin the photo, and that would not be very nice for Patrick. He was very demanding. He would have me move my foot to have a shadow of a certain length. I had to hold my foot exactly, just a little off the ground, for a very long time.

I would do what he asked me to. He didn't explain what he was doing. When it was over he said I had been very good, that I was very patient. It was the first time someone was taking a picture of me like that, with lights like that and everything. I don't know if I could have lasted any longer because it took a long time and I was really tired at the end. I went to sleep. I went home and went to sleep.

Muriel Mimoun is Robin's mother:

I am sorry for the lousy recording with Robin. He was rather uneasy with the idea of having to speak to me about the photograph. It's not the same thing as speaking to you, when he would take it seriously and make his point. Talking to your mother you feel like hiding some place. Well, anyway. I'm not at ease with the idea of loving some pictures more that others. It's too frustrating for me to have to speak about what I see.

This is a picture of my son. I told you, when you first asked, I told you very spontaneously, 'this is not my boy'. It was an experience he had all by himself about which I didn't know anything. I remember when he came back from that picture taking, he was in fact very tired and stunned. He is a very nervous child, always moving. I think it took Patrick about two hours and a half, and I thought well my god, how can Robin stand that? He cannot even stand for two minutes without moving everything in his body. So he probably never told me anything about how the picture was made and what was said between Patrick and him.

I realise when I look at the picture that of course it's Robin, but it's a Robin that I don't have any idea of. It's Robin in another world which I didn't even care to imagine, just as I don't spend much time imagining what is happening to him when he's not with me. I didn't like the expression of Robin in it. What was most visible in his face was that expression of stubbornness. That is what has been the most difficult to manage, in my relationship with him anyway, in real life, in real mother-child experience. Also, I didn't like the clothes he wore. They were some old clothes he had. One day he had wanted to wear them and Patrick had seen him in these clothes. So Patrick said 'I want you to wear that same pullover and those same shoes, and same socks', and that's why he's dressed like this. Of course, it's another side of him. He looks a bit like a peasant boy. There's probably some reminder of peasants in my family. It's not something I like or dislike, but its quite another side of the sort of persons we try to be. Urban, rather delicate people. That makes me laugh.

This week I looked at myself in the mirror and I saw exactly the same stubbornness in my jaws, and it made me very happy to be able to see that in myself. Not just think it was something that Robin was exhibiting, somehow and sometimes against me.

We've had a sort of violent relationship for a while. Right now it's much better, much more comfortable. I remember two years ago there were very violent angers between us. It took me hours to calm down and to convince myself that Robin was a small boy, and that he was not a big brutal male of some kind. I looked at those hands in that light and that is probably where there is some of that feeling of something 'rustique', like peasants' hands. They are big hands. I don't know why, but I see them very big. I'm sort of surprised because that's not the way I see Robin's hands usually. How absent should the real person be from the picture, so that people can project or can imagine whatever they want? I've realised, talking about it, that there is so much presence in this picture of the thing that was most difficult for me to live with, with Robin, at that moment. It has been over for a long time, but it really got very, very difficult as he was growing up and I could see no end to it.

At this very moment there's something heart-breaking at being faced again with all these memories of how I felt. I felt very vulnerable in front of this raw, rough, brute boy that was mine and that didn't look at all or feel at all like the little boy I had when he was younger, or when he was at ease with himself and with me. That's exactly the kind of memory that is brought up when I look at school class photographs, you know those nice pictures, where you see your boy smiling sweetly. Of course I'd rather remember these ones than the ache I get at the memory of the passion of not being able simply to be close. We could just get so wild at times and really not be able to do anything. This is getting quite intimate.

I think the most difficult thing about this photograph is that it really emphasises two sides of... I don't know if it's Patrick's art or just the way I hold on to memories that can make me hurt again for years afterwards. I'm trying to forget and to feel confident that it is all past, that as Robin is growing up it will be easier to smooth things and to just ride upon the air... I don't know how I could say that otherwise... The other side to this picture is how, on the contrary, you can just feel that Robin is absent. Robin's feelings are just absent from the way he looks, and from the way he is sitting, very erect in the chair. The chest of drawers is maybe like Patrick's life and he is just opening a tiny little bit one of the drawers, just as if it was a point of his own life that he wanted to let us have a glimpse into... showing this boy, any boy, dressed like one in the 50s, so that neither Robin nor I can even think why he had these clothes on... on that very day that Patrick came to our home... We weren't seeing a lot of each other at that moment, and Patrick had never said well I'll make a picture of Robin one day. But that very day he saw Robin and he said 'I have to make a picture of you with these clothes on and don't forget to bring them with you for the photograph'. So I guess the whole atmosphere that was created by the way Robin wore these very clothes brought something up in Patrick that was probably something very close to him, very personal to him that he might have wanted to contemplate once more.

I don't know if 'contemplate' is a good word. There is no sign that when Patrick is working he is contemplating. He is very active, bringing together objects and light and shade. But at the same time, he leads the person he wants to photograph to abandon, to leave behind all he is feeling and just get to the point where he is only occupied with the position he has to keep. What is very interesting in this picture is the momentum of the body trying to be sad and at the same time to find another balance in the toes. Those hands on the knees. To be very much existing, not as Robin or as somebody, but as representation of something that cannot be expressed in words, I think.

Now if I look at the picture again I just forget about the real Robin and the real feelings I had and the real story around it. I get to the point where Robin's personality is fading, just to leave a sort of absence of feelings, absence of colours, absence of expressions, absence of words. What is left is just a climate, a ground on which you can let anything grow. There is only one big contrast, between shade and light, between life and death, and how we manage to slide from one world into another.

I'm trying to think of an author who would be close to whatever Patrick is doing in his photographs. The one that was revived is Fernando Pessoa. He was a man of so many identities and so many masks, and even so many names. There is one little excerpt I have memorised, 'Je ne suis personne. Je suis la personage dans un roman qui reste l'écrire...' 'I am nobody. I am only the character of a novel that is still to be written. And I float in the air, scattered around before I have been, among the dreams of somebody who has not been able to achieve me.' I hope it makes sense. It's from The Book of Disquiet.

Floating women have been painted by the ancient Romans and Botticelli, but floating men are probably a creation of our century. Maybe you've read that book by Paul Auster, Vertigo, which I enjoyed very much. I was thinking of this while thinking of Pessoa and Robin, and the way Robin is not floating in the picture, but has momentum. This makes the picture a happy one. There is a happy aerial feeling about it. It gets rid of the profound; in fact we are probably just floating. Floating as well as we can. Not too well, but just trying to float and not fall down on our faces. The picture can evoke anything that people want to find in it. Everyone can invent, probably a short story about the boy and the photograph, the way the photograph was built and realised.

There is some sadness about having to stop here. Not because I don't have anything to say anymore. I could only go on with help. I hope whatever we've said will help you.

'Paris, 1996' is the first in a series of commissioned features by fiction writers. Matthew Stadler has written three novels; his fourth, Allan Stein, will be published by HarperCollins next winter.