Post-Internet Aesthetics and Brain-Eating Amoeba: The Shows to See in Beijing

Ahead of Gallery Weekend Beijing, a run-down of the best exhibitions in China’s capital

Ahead of Gallery Weekend Beijing, a run-down of the best exhibitions in China’s capital

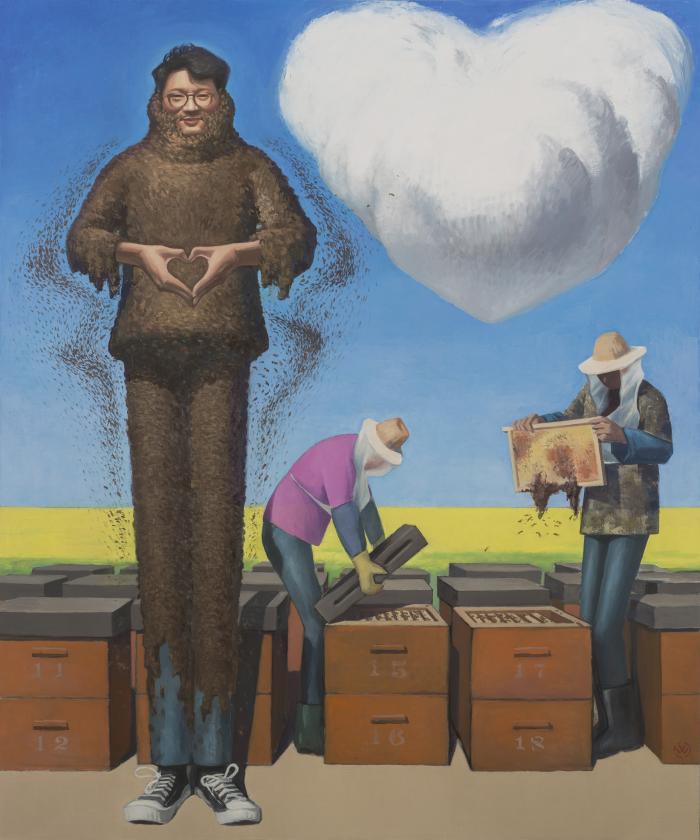

Wang Xingwei

Galerie Urs Meile

21 March – 12 May

Since the 1980s, when the demise of the Cultural Revolution helped cause Chinese contemporary art to boom, Wang Xingwei has remained steadfastly dedicated to his methodical painting practice. The artist’s latest solo exhibition, ‘The Code of Physiognomy’, focuses on portraiture – although never at the expense of the expansive landscapes that sit behind his studied characters. The works evoke impressionist plein air painting, Gustave Courbet’s densely impastoed landscapes and an attention to human form reminiscent of socialist realism. The show’s central focus are two large, four-panel polyptychs. Noon Break (2017–19) depicts Japanese soldiers and, in one panel, Wang with fellow artist Ai Weiwei – a tongue-in-cheek allusion to a much-publicized feud between the two. Technically, the work is a virtuoso demonstration of Wang’s belief in the traditional foundations of painting: colour, composition and form manipulated to create an alluring artwork. Four Seasons (2016–17), the other four-panel polyptych, depicts well-known Chinese politicians – including Bo Xilai and Ling Jihua – who were charged with corruption; each is a loose personification of one of the four seasons. There’s an appealing sense of anachronism both here and in Wang’s practice in general, with his relatively traditional approach to painting offset by contemporary references and a gently disconcerting humour.

anusman

Tabula Rasa Gallery

16 March – 4 May

In ‘Market Street’, his second solo exhibition at Tabula Rasa Gallery, self-described comic artist anusman (Wang Shuo) couples witty quotidian scenes – which he refers to as ‘obscure trivialities’ – with traditional artistic techniques, such as brush-and-ink shan shui landscapes. Feng Ji Ning Shen (2018) shows a monk-like figure, seemingly deep in meditation, before a karst landform; however, the playful inscription, written in traditional Chinese characters, describes a journey on the subway and the potential dangers of overusing mobile phones. Fighting for Veg (2019), featuring a group of highly stylized figures perusing a market seller’s goods displayed on a rug, extends beyond the gallery wall and into the exhibition space, where anusman has set up mini-stalls selling trinkets he designed. This refreshing exhibition delights in its own witty irreverence.

Nhozagri

Space Station

2 March – 7 April

In ‘Mouth Eye Qi Foot Mouth’, Beijing-based artist Nhozagri creates a world of fluffy toys and pastel-hued drawings of cheerful imaginary creatures; in the background, hypnotic, theme-park-like music emanates from the exhibition’s sole video work, The Shape of a Four-Dimensional Story (2015). Nhozagri’s idiosyncratic working practice – defined by the show’s curator, Fu Xiaodong, as a ‘sweet girl style’ – is here applied to an exploration of particles, cells and amoeba: a scientific subject matter that is regularly the focus of Space Station shows. While amoeba are generally known for their remarkable ability to reproduce and proliferate, some have a more ominous function: the potentially fatal Naegleria fowleri, for instance, which is known as the ‘brain-eating amoeba’ due to the way it can enter the body through the nose and consume human brain cells. Fu describes the exhibition, this ‘Nhozagri kingdom’ – in which misshapen, playful monsters jump and frolic – as the artist’s ode to the curious existence of these amoeba that ‘infinitely rebound with human existence’ and have their own ‘complex minds’. Nhozagri’s world may look cute, but it carries ominous undertones.

Liu Shiyuan

White Space

9 March – 1 May

Despite Caochangdi, Beijing’s second art district, facing an uncertain future, White Space, which is located in the area, continues to present excellent shows by young, forward-thinking artists. ‘In Other Words, Please Be True’, Liu Shiyuan’s latest exhibition, demonstrates the artist’s astute ability to create a visual language that encapsulates the contradictions and difficulties of our post-internet era. In the right-hand exhibition space, having navigated our way through a tunnel of bead hangings, we arrive at the four-part video A Sudden Zone (2019), in which a phone conversation between two teenagers is jarringly interrupted by a fragmented piano soundtrack and by people listening in on the call. A sense of foreboding manifests through a building sexual tension: ‘What would you do’, asks the boy, ‘if I took off all my clothes in front of you?’ Set in the pre-internet age of landline phones, the film nonetheless contains segments clearly referencing the digital era, in which a deluge of images flickers so rapidly across the screen that it’s impossible to grasp its meaning. In the left-hand exhibition space, ‘A Shaking We’ (2018), a series of photographic works, comprising similarly repeated imagery overlaid with text from unknown sources, continues this overload of visual stimuli. In an age in which information and images abound, Liu implies, it’s difficult to find a stable footing for understanding.

Richard Tuttle

M Woods

16 March – 16 June

M Woods is steadily building a reputation for hosting retrospective surveys that bring the work of significant American artists to Chinese audiences. ‘Introduction to Practice’, curated by Victor Wang, is a selection of one hundred works by Richard Tuttle – dating from the 1960s to the present day – arranged in ‘clusters’ of three to represent particular series. Observing the works installed in this way helps clarify the logic underlying Tuttle’s consciously delicate positioning of his art between drawing, painting and sculpture, and between minimalism and abstraction. At times, works are difficult to locate: the white ‘Paper Octagonals’ (1970/2019) are barely visible against the white museum walls; tiny rope creations from the ‘Rope Piece’ (1974/2019) series pass almost unnoticed; thin pieces of wire, continuations of ‘Wire Piece’ (1972/2019), lay surreptitiously on the floor. Wang’s methodical approach to curation – evidenced in the clearly numbered information panels and the addition of unusually shaped partitions throughout the space, some of which act as supports for works – encourages viewers to slow their pace and truly engage with Tuttle’s oeuvre.

Ko Sin Tung

The Bunker

26 January – 29 March

Situated within a compound with a long history, The Bunker, which as the name suggests was formerly an air-raid shelter, is a unique exhibition space in Beijing. It’s also host to Hong Kong artist Ko Sin Tung’s first solo exhibition in mainland China, ‘Dust and Trivial Matters’, in which the artist has covered the crevices and porticoes of the bunker with a clingfilm-like plastic screen. Behind some of the sections segmented by this semi-opaque film are a number of bisected objects, including a fish tank, plates and a clock. The other halves of these items have been ground up into fragments and pumped through the filtration system to be deposited in the last room of the winding space. While there is a sense of process, the overriding feeling is one of medical cleanliness. Metal tables and instruments look hospital-like, videos show the objects being wiped over and over while the pervasive plastic screens quarantine them from us. The show has the distinctly eerie quality, intensified by its underground location, of a past emergency frozen in time – echoing the unique site of the The Bunker.

Liu Heung Shing

Star Gallery

20 March – 18 May

In ‘Spring Breeze’, Star Gallery’s inaugural exhibition at its new space, the photographs of Liu Heung Shing operate as compass points for navigating the massive changes that occurred in China during the late 1970s and 1980s. The images range from a 1981 image of a student flamboyantly rollerskating past a statue of Chairman Mao in the coastal city of Dalian, to another 1981 image showing construction workers at the National Museum of China in Tiananmen Square removing one of the ubiquitous giant portraits of Chairman Mao as part of a programme aimed at stalling the personality cult that had burgeoned around him. Another image, also from 1981, shows a pack of cyclists on a newly-built road in the centre of Beijing. This, and some other of the show’s images, might be seen as veiled references to pivotal moments in Chinese history that the photographer witnessed, but the direct documentation of which was too sensitive to exhibit. ‘Spring Breeze’ makes clear that Heung Shing’s great skill as an artist lies in his ability to capture the extraordinary evolutions in late-20th-century Chinese history in single images.

Main image: Liu Shiyuan, A Sudden Zone, 2019, film still. Courtesy: the artist and White Space, Beijing