Postcards from Manifesta

A series of regular reports from Manifesta 7

A series of regular reports from Manifesta 7

Thursday 17th July: Part 1

Just got back to my hotel room after attending the opening of Adam Budak’s ‘Principle Hope’ in Rovereto – one of the four exhibitions that combine to form Manifesta 7, this year being held in Italy’s South Tyrol region.

First things first. The four towns in which Manifesta is sited (to be precise, three towns and a fortress) are strung through the Adige valley, which stretches from the Austrian border near Innsbruck down to Lake Garda in the south. We flew to Verona, which is 40 minutes on an extremely comfortable train from Rovereto, and only 20 minutes more from the pretty town of Trento, where we are staying. Trento is the base for Anselm Franke and Hila Peleg’s ‘The Soul (or, Much Trouble in the Transportation of Souls)’, which I’m off to see in a few minutes. Tomorrow we’re looking forward to the Raqs Media Collective’s ‘The Rest of Now’, in Bolzano, and the collaboratively curated ‘Scenarios’, in the hilltop fortress of Fortezza. It’s possible to buy a ticket for the exhibitions which includes travel between venues on all local rail and bus services.

Back to Budak’s exhibition. ‘Principle of Hope’ occupies a large building around two courtyards that formerly housed a tobacco factory, as well as a smaller warehouse space, ‘Ex Peterlini’, on the other side of town. The show’s title is borrowed from Ernst Bloch, and refers to the optimistic notion of ‘critical regionalism’, which, as Budak states, is ‘a means to resolve tensions between globalization and localism, modernity and tradition’ in which local life reaches a state of self-aware criticality. While this is doubtlessly an interesting starting point, the show does little in terms of elucidation. Long, discursive wall texts (in tiny font) accompany each work, dropping references to ‘trans-rational spatial categories’ or claims that ‘the artists penetrate the borderlines of knowledge and science’. Despite this, there are many excellent works (as well as plenty that were the aesthetic equivalent of eating ten cheese crackers with a dry mouth). Highlights for me included Ragnar Kjartansson’s performance (in which two suited gentleman sang German love songs inside a painted depiction of hell), João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva’s extraordinary installation of their quasi-archaeological films, and Barbora Klímová’s videoed restagings of canonical Czech performance art, accompanied by commentary by the original artists.

Now I’m running off to Anselm Franke and Hila Peleg’s contribution, which, from the list of artists, appears to be quite a different proposition.

Thursday 17th July: Part 2

What a relief! ‘The Soul (or, Much Trouble in the Transportation of Souls)’, which has set up shop in Trento’s fascist-built Palazzo della Poste (its former post office, pictured above), provided many more enjoyable surprises than the exhibition in Rovereto. A short bus or train ride up the valley, Trento is the nominal centre of the region. It is also the town that wears a sense of its own history most proudly, something that is embodied in the medieval architecture dotted throughout the largely pedestrianised town centre.

Anselm Franke and Hila Peleg’s exhibition focuses on the idea of Europe as a political entity that is beginning to turn in on itself, a continent that regards its own psyche – or multitude of psyches – as the next frontier to be crossed, rather than its bulging geographical borders. Broadly speaking, this is a show about interiority, sharpening its political talons on the proposition that the psyche – or soul, as it was once called – is nothing more than a cultural construct, an idea that the Catholic church of Trento itself significantly contributed to some 500 years ago.

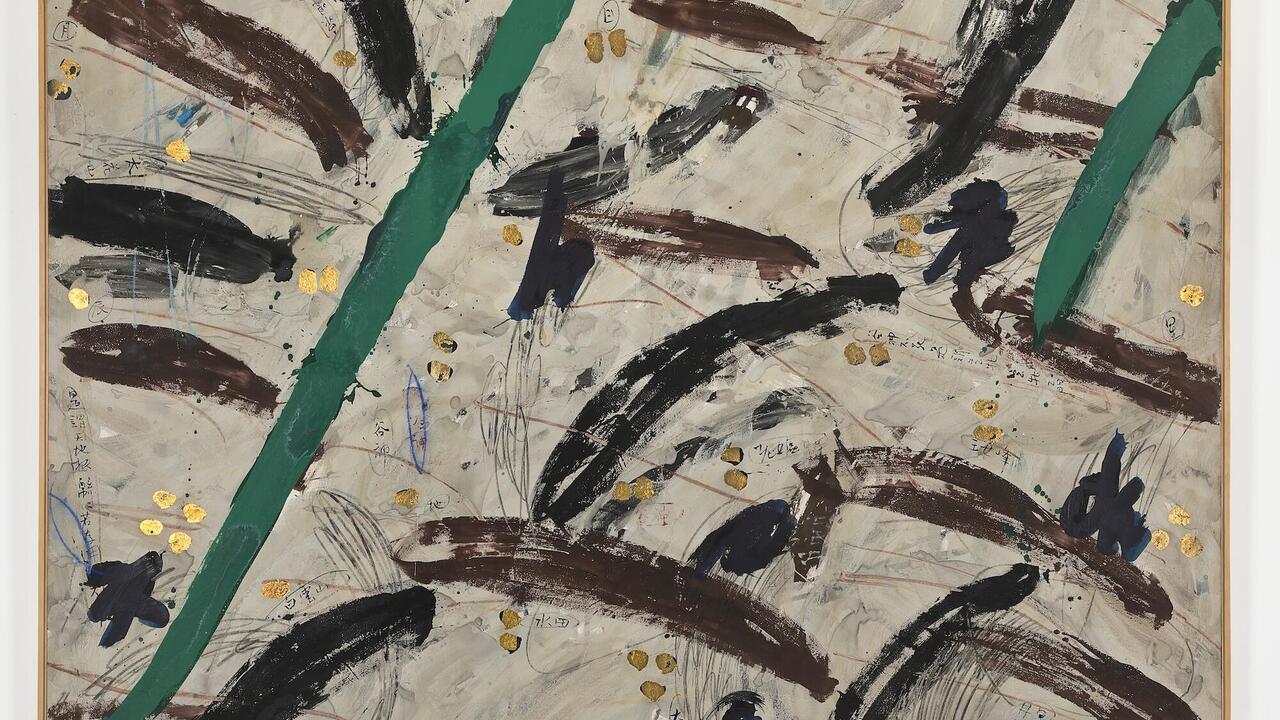

From Luigi Ontani’s sexualised holograms of Asian boys, and Bernd Ribbeck’s cosmic, lush, abstract ink drawings, it was clear that Franke and Peleg’s tastes are quite different to those of Budak. Pietro Roccasalva followed soon afterwards, with an extraordinary series of works over two adjacent rooms, one installation involving snaking neon and a small painting bearing the memorable title Jockey Full of Bourbon II (2006). Mostly, however, artists were given just one room each – turgid wall texts notable by their absence. The exhibition was spread principally over the first and second floors, the smallish rooms circling a central courtyard. A high proportion of the show is video- or film-based (I’d guess at around half), which in a hot, close climate does not make for a hugely enjoyable viewing experience. However the quality of the work countered the audience’s resentment: strong – and very often new – film and video works from Omer Fast, Karl Holmqvist, Rosalind Nashashibi, Javier Téllez, and Angela Melitopoulos were carefully presented, the last being a particular highlight and an artist previously unknown to me.

The exhibition also stood out for its use of mini-museums to break up the pace of the show. At various corners of the building galleries were given over to invited artists and academics who created displays on themes such as ‘The Museum of Projective Personality Testing’ (revealing various defunct psychoanalytical evaluation methods) or ‘The Museum of the Stealing of Souls’ (which explained how the notion that photography was thought by certain peoples to steal the subject’s soul is largely a colonial myth propagated by those hoping to extend the impression of these societies as innocent, primitive cultures). A lot to digest. I’ll sleep well tonight.

Friday 18th July: Part 1

We caught a bus first thing this morning which took about an hour up the valley to Fortezza, the site of the 1830s’ Habsburg hilltop fortress (in the South Tyrol there seems to be a great many hilltop fortresses) in which all six curators collaborated to produce the exhibition ‘Scenarios’. The derelict building has clearly had some care lavished upon it in preparation for Manifesta: elevators, cloakrooms, toilets – even a pair of striking elevated walkways over the river are installed sensitively and imaginatively. Following its role as a defensive military outpost, the fortress was put to use by the Nazis during World War II as a depository for stolen gold, and subsequently an ammunition depot (grids of metal lightning conductors are still nervously strapped over all its roofs).

Unable to pass up the offer of the site but understandably anxious about pitching art works against the heady atmospherics seeping from its walls, the curatorial team agreed to invite ten writers to contribute texts responding to the place, which were then recorded by actors and are exhibited as sound works throughout the building. A distinctly Sebaldian sediment of historical projections, testimonies and conjured memories is stirred through the fortress’s cold damp chambers. Diverse presentation techniques are employed: some pieces can be heard on headphones or out of speakers; others emanate from beneath Martino Gamper’s specially commissioned chairs. Margareth Obexer’s text Defending Europe (2008) can be heard by holding wooden discs, attached to taut strings, to one’s ear. Of course, sound work of this kind benefits from patience and reflective silence, both of which was in short supply amongst the excited hordes at the press opening this morning.

In contrast to the auditory nature of the exhibition’s core works, however, one large building is devoted to a silent film programme. Five films are projected on the interior walls of the darkened space, the most affecting of which is Harun Farocki’s extraordinary Respite (2007), a devastating reworking of found footage from the Westerbork concentration camp in which Farocki uses intertitles to direct our reading of the ostensibly innocent images. The film’s attention to the background hum of its source material chimed clearly not just with the audio works but also with sculptor Philippe Rahm’s installation Climate Uchronia (2008). Rahm had affixed ominous black-backed lightboxes over the outside of certain windows in the fortress, which reproduced exactly the effect of daylight in the room inside. Moments after watching Farocki’s film, listening to Mladen Dolar’s The Voice and the Fortress (2008) under the silently malignant light of one of Rahm’s lightboxes, I felt the exhibition pull focus for a moment into a cohesive, powerful and generous experience. And it’s not often you get to say that.

Friday 18th July: Part 2

We turned back down the valley for the final section of Manifesta 7: Raqs Media Collective’s ‘The Rest of Now’ in Bolzano’s Alumix building – a former aluminium factory on the edge of town, now surrounded by newer light industrial units, car dealerships and roundabouts. Raqs’ curatorial mood-board was a spidery diagram of ideas, which connected references to Futurism, to aluminium’s function as the metal of propulsion and violence, light and speed, industrial, social and artistic residue and sediment, environmentalism and ultimately the problem of how to deal with what is left over. Part of this thesis drew on and extended their 2005 essay ‘With Respect to Residue’, which they quoted in much of the exhibition’s literature.

The building itself provided Manifesta’s only large open exhibition space, all of the other shows having been divided into sequences of smaller rooms. This came as a pleasant change, the works having more room to interact and start their own non-linear conversations. The exhibition started well enough, with a presentation of the work of Italian underground musician and comic artist Professor Bad Trip, who died in 2006, which segued into a cyber-hippy bus driven across Europe by the Swedish founders of file-sharing website Pirate Bay, currently beset by copyright litigation. This was an early peak however; while the central space had a lively dynamic in terms of the placement of works (dominated by Zilvinas Kempinas’ videotape floor-to-ceiling Skylight Tower, 2008, and Nikolaus Hirsch and Michel Müller’s wooden Cybermohalla Hub, 2007) the quality of the works themselves often seemed lacking, as if they were serving primarily to flesh out the curatorial premise. Clichés that most artists left behind after the first year at art school were dusted off for reuse: photographs printed onto fabric hung on clothes lines, piles of obsolete televisions, latex casts of dusty surfaces and a performance whose self-seriousness left me trying not to giggle were among the worst culprits. By now it was also possible to spot recurrent Manifesta trademarks: indexes and archives, audio-works, collaborative and/or research-based practices and allusions to post-war German guilt.

I should close this report with a caveat: my responses here are by no means consensual and I have spoken to plenty of people who have entirely different views on Manifesta to my own. There are those who feel that Franke and Peleg’s show in Trento was a safe, overly passive viewing experience, and that it was Budak who most challenged the viewer with a rigorous and incisively researched exhibition. Others have ventured that Raqs’ show in Bolzano’s Alumix building was the only piece of consistent and cohesive curation in Manifesta 7, and that the exhibition in the fortress was a monotone washout. Ultimately I think this is testament to the overall quality of the biennial, and of the fact that, while the four exhibitions may take distinctly different approaches, as whole Manifesta 7 is a tough, intelligent and serious endeavour, and worthy of the pan-European discussion that it hopes to instigate.