Premier Mouvements – Fragile Correspondances

Le Plateau, Paris, France

Le Plateau, Paris, France

Perhaps it is because it's situated in an area of Paris where you don't usually see much art, or because it opened on a much smaller scale and to much less fanfare than, say, the Palais de Tokyo, but the recently opened gallery Le Plateau has hardly received the attention it deserves. That said, perhaps the best way to respond to 'Premiers Mouvements - Fragiles Correspondances' (First Movements - Fragile Connections) might be not to review it at all.

The exhibition included a group of works by economist-turned-poet-turned-Fluxus-artist Robert Filliou, who died in 1987, spanning the 1960s to the 1980s. Extending Raymond Roussel's playful approach to language, Kurt Schwitters' constructions and Marcel Duchamp's interrogations of the function of the work of art, Filliou stuck scripted words, nails, rubber-stamped letters and torn photographs on to found wood and scraps of cardboard. In the 1970s he made editions of small cardboard boxes that contained a photograph of himself in white overalls cleaning a work of art in the Louvre or MoMA, and a cloth covered in what he described as the 'dust of dust'. As his rags touched the surfaces of the art works Filliou also managed to touch on a hidden nerve - the public's continuing fascination with the aura of masterpieces, and on the ways in which avant-garde gestures can gather dust as quickly as any old master.

Poussière de poussière de l'effet Pevsner (monument symbolisant la liberation de l'esprit) (Dust of dust of the Pevsner effect, monument symbolizing the liberation of the spirit, 1977) was among the 30 pieces on show here. A few works by Filliou's contemporaries as well as more recent art works radiated out like spokes from one of Filliou's recycled bicycle wheels. The awkward way they occupied the rooms - unframed, on the floor or hung by a tangle of wires and nails - reinforced the impression of unsteadiness, as if the gallery's director, Eric Corne, and guest curator Sylvie Jouval understood well that to show these works using 'conventional' means was to diffuse their critique.

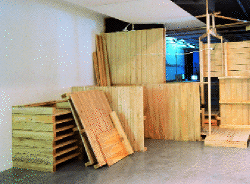

André Cadere's 'painting' Barre de bois rond (Round bar of wood, 1970) was displayed leaning against a wall, as if Cadere himself had just smuggled in the multi-coloured rod and left it there (as he did in so many exhibitions throughout the 1970s). A video monitor offered flickering traces of Gordon Matta-Clark making 'cuts' into a soon-to-be-demolished building next to the construction site for the Centre Georges Pompidou in Conical Intersect (1974) and explored the underside of the capital of culture in Sous-sol de Paris (Paris Sewers, 1977). Although it's a shame that several of the contemporary works included were less than memorable, the best of them trod a fine line between presence and self-effacement, criticality and modesty. Eric Hattan, for example, produced an edition of 1000 postcards bearing the title Eric Hattan Cède sa Place à une Artiste (Eric Hattan Cedes his Place to a Female Artist, 2002). Dana Wyse's Objects Trouvés dans mon Coeur (Objects Found in my Heart, 2002) - a collection that included a ready-to-bake cake, Sweethearts candies and postcard-perfect mountains - looked like souvenirs of fleeting moments of home comforts, flirtation or travel. Beneath the pastel charm and seeming intimacy this Postmodern vanitas tells a less pretty tale of ready-made memory constructed by mass-market images. In a corner Francisco Ruiz de Infante erected a wobbly, low-ceiling structure of unfinished wood, nails and snaking electrical wires. Periscopic holes and surveillance monitors transmitted images of the basement and other hidden places, yet I was never entirely sure what I was being shown, because to crouch and stumble across shaky planks through 3 + 5 = 8 Mètres en tout (3 + 5 = 8 Metres in All, 2002) was to distrust what one saw.

Precariousness, transience, displacement and simplicity were some of the Filliouesque threads that ran through the various works, but the show as a whole could most accurately be described as a revelation into the less than clean underbelly of art and its institutions. Neither a true retrospective of Filliou's work nor a coherent overview of his influence, the exhibition was more like a manifesto - as if in the future art and art institutions will either be destabilizing, anti-monumental and critical ... or they won't be.