To the Raft of the Medusa

Martin Kippenberger

Martin Kippenberger

Two years ago, very little was heard of Martin Kippenberger. Things remained quiet into the first half of 1996, but that autumn, exhibition announcements came in thick and fast, from museums in Copenhagen, Esslingen, Mönchengladbach, Geneva, as well as numerous commercial galleries. Preparations for building another entrance to his world-wide 'Metro Net' started in Leipzig, and finally it was announced that he had won the Käthe Kollwitz Prize, which led to another exhibition, at the Akademie der Kunste in Berlin. The Kippenberger organisation seemed to be thundering into action all over Europe: it was like an ambush. But in Spring this year another piece of news came through. Kippenberger had died in Vienna on the evening of March 7th.

The artist had recently celebrated his 44th birthday; his work still had some of the dash and impudence of youth, even though he had unambiguously distanced himself from all the value judgements and misunderstandings associated with Jugend (Youth) in his 1982 work, Abschied vom Jugendbonus (Farewell to the Youth Bonus). It is difficult now to see his art as a thing of the past. It is also unpleasant to have to stand by as it is solemnly accepted by museums, those mausoleums of art, which had almost without exception rejected his work until now. No one wanted this disruptive and unpredictable artist in their building, although his last campaign would have made it hard for them to continue to reject, ignore and resent him. Now his numerous enemies in museums and in the press are starting to pretend they never played their pusillanimous games.

Kippenberger's Berlin exhibition opened a week after his death. Despite the ubiquitous obituaries, it attracted very little attention, and even fewer visitors. Compared with the recent series of very large museum shows, this was on a relatively modest scale: 24 oil paintings, a series of 15 lithographs and a carpet. But its concentrated and lucid approach made it amazingly impressive and deeply shocking - one of the most remarkable exhibitions in the last few years.

All the pictures circled round a single theme, Géricault's famous Raft of the Medusa, first shown in public in 1819 and now hanging in the Louvre's permanent collection. Many of us saw this great painting as children, subsequently retaining a clear mental image of it. Even without knowing the story behind the work, its monstrous images tend to sink into the memory and remain there, sowing a strange seed in the imagination, generation after generation. As adults, we begin to address the nature of the event - the various moments between hope and despair on those timbers - and some of the magic disappears. Shouldn't our rather more knowing eyes see the whole thing as clever stage management? After all, the ocean depths go no further than the edge of the picture - why don't the shipwrecked people save their lives by jumping onto the gilt-edged frame? The advent of photography and film this century has left the status of painting in the balance, hanging like a rag on a piece of wood. Géricault's work, however, intended as a metaphor for the shattered dreams of the French people 30 year after the revolution, still managed to carry its obscure social drama through two centuries. In doing so it encapsulates the inexplicable qualities that only painting possesses.

Today the facts of the shipwreck are more shocking than the picture could ever be, or at least shocking in a different way. The raft was 20 x 60 feet, intended to accommodate 150 people, submerged in water to their hips. At first it was towed by four lifeboats that carried the ship's better-off passengers, who soon cut the ropes so that their boats could reach land more safely. The raft drifted for twelve days. Bloody uprisings in the little order that remained cost many lives; other passengers slipped off during the night or died of hunger. Even when only 30 remained, there was not enough food and water, so they ate the flesh of the dead and drank their own urine. On the seventh day it was decided that they would divide the rest of the supplies among the stronger survivors and allow the others to die. 15 were still alive when The Argus hove into sight, and this is the moment between hope and despair, captured by Géricault.

In 1996, the organisers of the 'Memento Metropolis' exhibition in Copenhagen asked Kippenberger if they could show his installation Happy End für Franz Kafka's Amerika (A Happy Ending for Franz Kafka's America, 1994) alongside a full-sized copy of Géricault's painting. A few months later, strange black-and-white photographs began to appear in advertisements and on invitation cards, showing Kippenberger against an empty, white background. Bare from the waist up, with an alienated expression on his face, the poses he adopted turned out to have been based on motifs from Géricault's Raft.... Kippenberger's use of photography was poignant: this was the medium that would begin to question the future of Géricault's own medium - painting - shortly after his death. Kippenberger later reinstated the Raft of the Medusa in the form of several drawings that he made from the photographs. The pencil drawings are laborious copies, and Kippenberger may have drawn inspiration from the many studies on which Géricault based the sketch for his painting. While distancing himself from the original, Kippenberger simultaneously revisited the 19th-century studio.

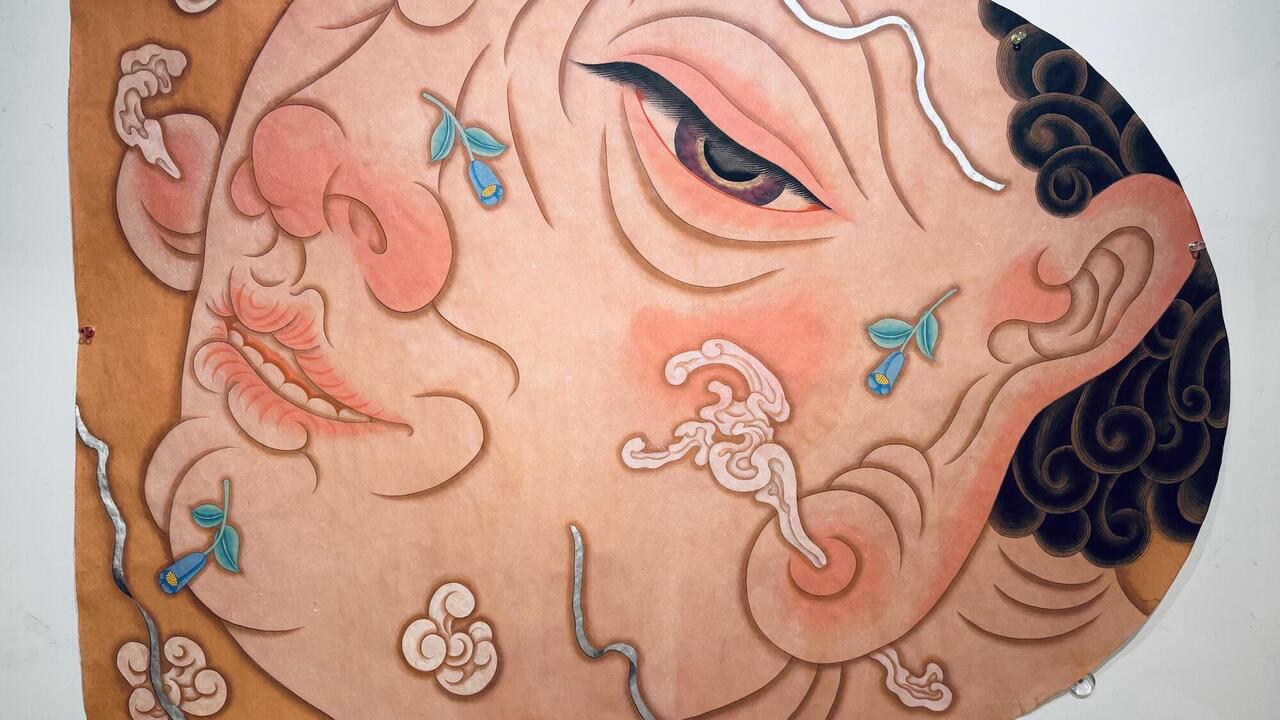

Various aspects of the drawings were then used to make the 24 paintings shown in Berlin. As usual he divided his canvases into many colour-fields, creating the simplest forms possible: sky and horizon, before and after, abstraction and colour. The perspectives alternate from above to side-on, and this interplay intensifies the visual experience: the images come out of the canvas, almost displacing the viewers as they stand in front of it, or turn away from them into the canvas, where an area of colour draws the eye to a child's drawing of a ship. Each painting retains the quality of the drawings, as if feeling for something, breaking it open, and concluding with a specific motif such as a large paralysed head based on a pose of Kippenberger's. Or else they fall apart in the lines of a naked man disappearing under a linen cloth, again a picture of the artist.

The anticipation of death contained in these self-portraits is hard to deny. Géricault - who is said to have modelled one of the shipwrecked figures on himself - died only a few years after completing the Raft..., at the age of 33. According to close friends, Kippenberger began this series in good spirits and was only able to appropriate the old master's dramatic scene because he did not see it as his own. He liked the work because, as a representation, it was not quite right: ultimately the situation on the raft is inconclusive. For this reason Kippenberger portrayed Géricault's picture as a memory, giving the work new life by cutting it into individual gestures and showing the viewer how they were remade. The process he used suggests the possibility that they can be read in the same way as traditional painting. It is as if Kippenberger decided for once not to exaggerate.

In the middle of the bright exhibition space lay a carpet with the motif of another reconstruction: a sketch of the raft made afterwards by two of the survivors. In their drawing they had laid timber after timber carefully together, differentiating between large and small, including the cross-braces and reinforcements on the sides, all well roped together. In Kippenberger's work these details were subsumed into the knotted fabric of a pale green carpet. The raft of the Medusa has left another image to posterity.

Translated by Michael Robinson