For Rindon Johnson, No Water is Neutral

The artist’s show at Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, sees his avatar swim across the Pacific in a journey simulated using real-time data

The artist’s show at Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, sees his avatar swim across the Pacific in a journey simulated using real-time data

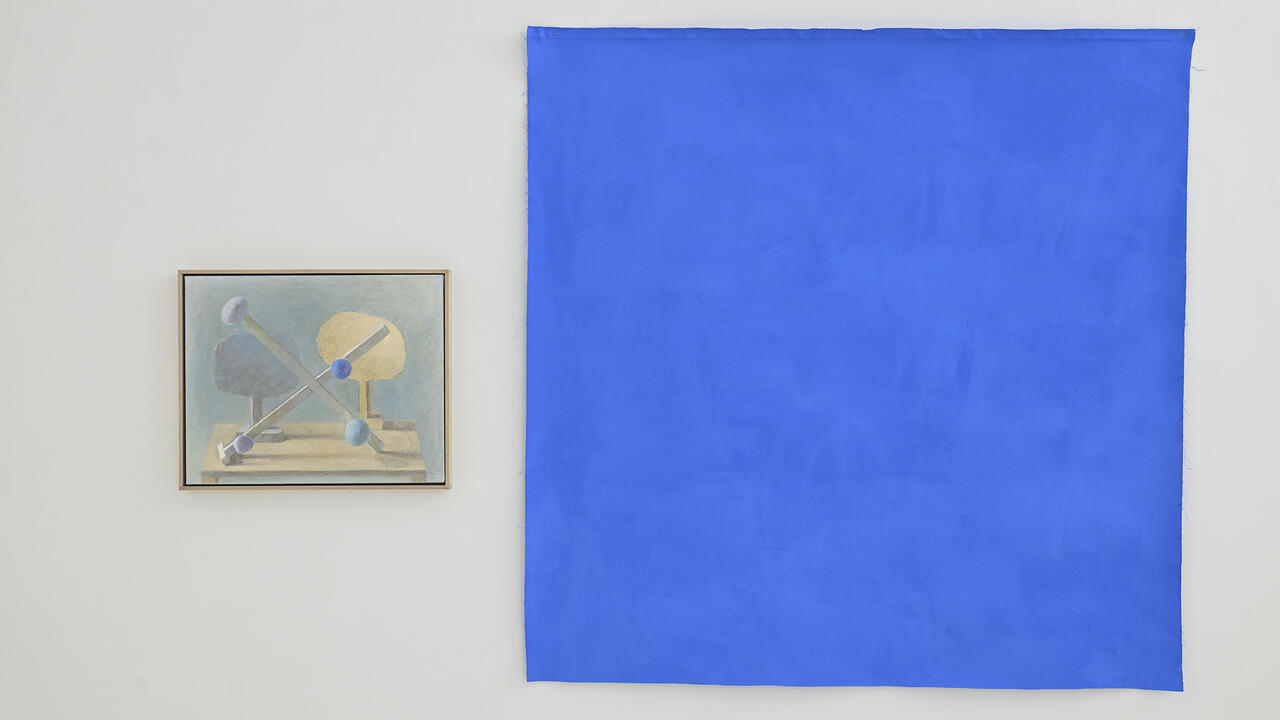

‘Best Synthetic Answer’, Rindon Johnson’s exhibition at the Rockbund Art Museum, opens with a question written on the floor at the entrance in wavy letters: ‘How does a Black American, raised on the edges of the Pacific, move through the ocean to reach Shanghai?’ Johnson’s answer: by swimming. The show’s centrepiece, the AI-generated video installation Best Synthetic Answer #1: Crossing ... (2024), sees the artist’s avatar virtually swim from his birthplace in San Francisco to Shanghai: a journey simulated using real-time and pre-existing oceanic weather data. (The work’s full title resists transcription by virtue of its length, akin to the titles of the other works on view.) The avatar’s journey follows the historical route of American imperialism: from Hawaii via island groups in the South Pacific. Just as the figure – who, like Johnson, is Black – swims through the ocean, so too the artist and poet navigates his relationship to the complex legacies these waters carry.

The ceiling above the video features a stained-glass map, almost 15 metres long, showing the entire Pacific region. Johnson’s work is broadly language-based, and the title of the large glass, Language is a virus or…(2024), doubles as a poem that explores the relationship between colonialism, standardization and value, as well as the ways in which new laws, languages, fashions and social conventions have accompanied the imperialist expropriation of land. In this light, the work’s coloured glass, typically found in Tiffany lamps, can be understood as a standardized luxury good of American origin.

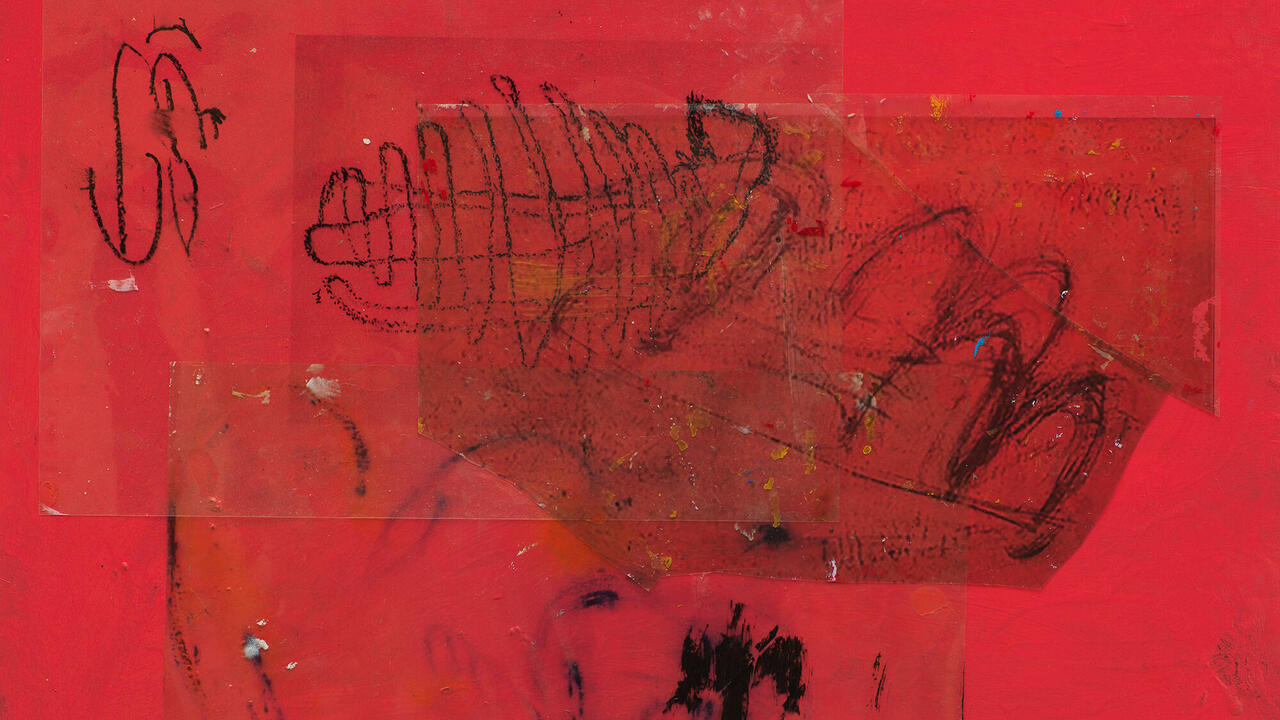

Generally, a map illustrates one particular worldview, but Johnson enables a change of perspective, as the cartographic window-ceiling can also be viewed from above on the upper floor. Alongside it are three of the artist’s painted leather works, the titles of each reflecting memories linked to the ocean: Well we were never on time …, I lay on my straw …, We realized that if we ran … (2024). Bold black lines that suggest structures such as windows or archways are overpainted with watercolour, bleach, wax and crayon in a highly gestural style. Johnson sees leather as a material entry point to addressing issues of autonomy and exploitation; it becomes a means to explore how various materials and bodies are linked under capitalist accumulation.

Johnson’s work may be language-based, but it’s also time-based. For Predator Swamping is common … (2024), he positioned a raw hide on the building’s roof, exposed to the changing weather conditions. Filmed by a CCTV camera, a livestreamed video within the museum testifies to the work’s existence and ongoing decay; at the time of writing, it has already been hit by two typhoons. Another temporal element is the soundtrack that plays throughout the exhibition. The synthetic composition mixes jazz generated using a large language model with jazz originals, speculatively representing how the music genre spread across the Pacific region and morphed at the avatar’s stations.

In the museum’s darkened lower level, an aquarium glows with light-producing algae; adjacent is a projected slideshow which changes monthly and draws on Johnson’s family albums from 1990–96. Photos of a Hawaii holiday in 1995, playing golf and swimming in the sea, show a carefree childhood in a prosperous Black family; these images are particularly vulnerable in that they depict the artist prior to his transition. The exhibition is conceived like a vertical cross-section of the ocean with the family archive forming the seabed. In this way, looking at Johnson’s own relationship with the ocean becomes a means of thinking about related questions of autonomy, power and capital, and the many threads of history that prove that no water is neutral – not even the water he played in as a child.

Rindon Johnson’s ‘Best Synthetic Answer’ is on view at Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, until 6 April

Main image: Rindon Johnson, ‘Best Synthetic Answer’, 2024, exhibition view. Courtesy: the artist and Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai