Rob Pruitt

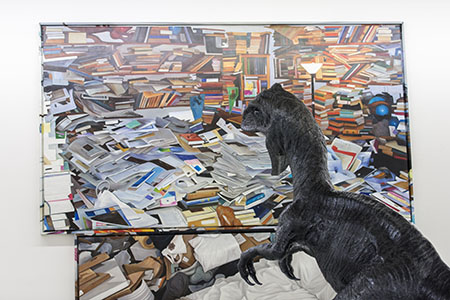

What to make of this truly bizarre exhibition, in which chrome-finish dinosaurs stood several metres high, looking at photo-realistic canvases, themselves several metres high, depicting rooms crammed full of junk? The show’s author, Rob Pruitt, traffics in excess. From his saccharine, glitter-drenched ‘Panda’ paintings, which he first showed in 2000, to his 2009 exhibition ‘iPruitt’, comprising thousands of iPhone photos, Pruitt borrows some of our cultural common denominators (Paris Hilton, mineral water, dinosaurs or that most contemporary of sicknesses, ‘hoarding’ syndrome) and reworks them into bigger, brasher, louder versions of themselves. Subtle he is not.

The inflection of this exhibition, immodestly titled ‘The History of the World’, was ambivalent, however. Was this a damning cultural commentary on the bankruptcy of a consumer society, suffocated by the very products of its insatiable consumption? Did it intend to present a critical portrait of the US, the artist’s home country (and home also to the award-winning reality TV series Hoarders, from which the paintings’ imagery was taken)? Did it portray the 20th century’s foremost nation as a massive dinosaur of stumbling inefficiency, particularly when compared with China, its productive successor, where the paintings themselves were made? Or was it meant to be a metaphor for the inflated art market? (At Art Basel, not far from Freiburg, not dissimilar large sculptures or realistic paintings produced in China, made by other artists of the same generation, were concurrently changing hands for considerable sums.) The combination of brash visual impact with calculated ambivalence is at the heart of Pruitt’s production.

It is on this narrow ridge of irony that Pruitt’s exhibition swung from downright awfulness to brilliance – perhaps – for it swung back just as easily. There was always the niggling sense that he may be calling our bluff in presenting us with something so obvious, or so overblown, that it is either barely visible or totally overwhelming. The massive scale of the dinosaurs, manufactured out of Styrofoam by a supplier for natural history museums, contrasted sharply with their prop-like levity and glitzy coating. The paintings – assembled in groups and sometimes stacked or turned on their sides – depicting living rooms littered with papers, cardboard boxes and consumable goods, became depopulated, desperate landscapes. The dinosaurs’ curiosity, as they peer at this incomprehensible phenomenon, echoes our own. What leads people to this obsessive need to collect things, regardless of their worth, use or hygienic conditions? And why have they been painted on these enormous canvases?

A final element brought the exhibition full circle. Building on his successful ‘Flea Markets’, the first of which took place in New York in 1999, with more recent incarnations at Tate Modern in London and the Monnaie in Paris, Pruitt invited a local charity shop to relocate to the Kunstverein in order to sell their goods. The balcony that circles the lofty exhibition space (which was originally a public swimming pool) was packed full of bric-à-brac: clothing cast-offs hung over the balconies, junky china and books on amateur photography were arrayed on bulky pieces of furniture. Decorative ornaments and out-dated household goods were stacked in every corner. Each item sold received a label signed by the artist: an instant transformation of junk into art, along the lines of Pruitt’s ongoing Martha Stewart-meets-conceptualism project ‘101 Art Ideas You Can Do Yourself’.

In this ambivalent commentary on the nature of contemporary society, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure. But as Pruitt wraps his commentary in the very trappings he is supposedly criticizing – consumption as culture – its message bounces back at us obliquely. There is no objective critical position here; we are all implicated. Even if we are not all sick, we are at least contaminated. This exhibition, as with much of Pruitt’s work, presented us with a distorted mirror-image of ourselves, and in so doing became a kind of cultural empathy at work. It repelled as it attracted, but it was inescapable. Instead of asking that unresolved question, what happened to the dinosaurs, we are invited to ask, what is happening to us?