Rosângela Rennó

Scratches and blotches on bleached-out film stock copied to video and not much else: just the sound of sea and wind. The opening titles reveal that the year is 1500AD, and only the sparse subtitles tell the story of the discovery of an unknown land (‘Land ahoy, captain!’ ‘Careful, Bartolomeu, they are carrying bows!’). These fragments of text are based on Pêro Vaz de Caminha’s famous letter to the king of Portugal, in which he reported coming upon the landmass of Brazil.

Rosângela Rennó’s video Vera Cruz (2000) was born out of the curious frustration that the letter produces. Its descriptions of Portuguese sailors idling on the beach, haltingly trying to communicate with the indigenous Tupiniquim, inevitably only gives the conquerors’ perspective. Rennó, with adequate absurdness, responds to the lack of a full picture – and the start of a long history of neglect of Brazil’s indigenous peoples – by producing a phantom film from the 16th century.

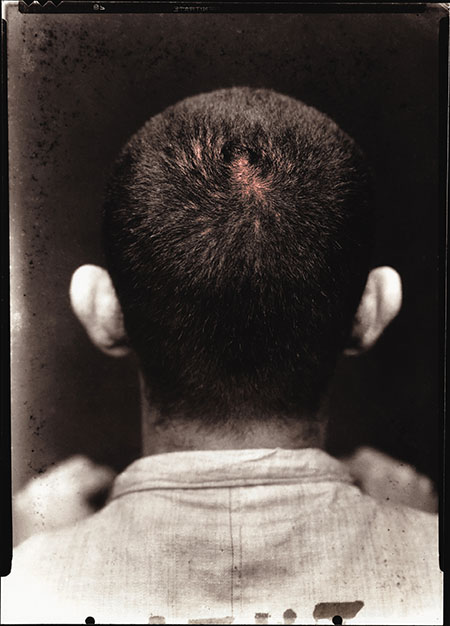

The exhibition ‘Strange Fruits’ at Fotomuseum Winterthur surveyed this impulse, which has propelled Rennó’s work for more than 20 years: to transform the factually lost into the fantastically retrieved. As much as Vera Cruz pushed a written source towards a phantom image, her two-part early work Duas lições de realismo fantástico (Two Lessons in Fantastic Realism, 1991) extracts transcendence from mug shots. The exhibition leaflet described the missing persons in these found portraits as having been ‘“crushed” by the system or driven to insanity’, leaving us to speculate how many of them fell victim to Brazil’s dictatorship (which ended in 1985). The first ‘lesson’ was a gallery of enlarged prints in which the subjects look ‘normal’; but once you start zooming in, a sternly bitten lip or glassy stare, combined with the bleached or clouded quality of the print, seem to reflect a threat to their livelihoods, or their sanity. In the second ‘lesson’, the portraits reappeared in a carousel of negatives projected from inside slender stelae that double as magic lanterns: phantasmagoric ghosts hovering along one side of the room, turning in circles like a dystopian merry-go-round in a magic realism of the missing.

Rennó repeatedly returns to found photos scavenged from flea markets and archives around the world. At times, as in the series ‘Vermelha’ (Red, 1996–2003) – enlarged images of people in military uniform drenched in a blood-red hue – she tends towards the demonstrative or emblematic, halfway between Christian Boltanski and Alfredo Jaar. At other times, her approach is at once cooler and gentler: the news photos of people holding up images of dead or missing loved ones, in a mixture of mourning and protest, in the series ‘Corpa da Alma’ (Body of Soul, 2003–09) are engraved, in grainy half tone dots, onto reflective steel sheets. Like extra-large daguerreotype plates, these images only emerge from the opaque surface at certain angles of incidence. Aptly intangible, they disturb the rapport between viewer and viewed, as if reacting to Susan Sontag’s statement that ‘no “we” should be taken for granted when the subject is looking at other people’s pain’.

In ‘Biblioteca’ (Library, 2002), 100 scavenged personal photo albums or slide boxes are encased in desk-like vitrines (installed in groups of ten). A filing cabinet provides written assessments of the objects, but it is only in the book Biblioteca (2003) that we get to see Renno’s own selection of images from the material, comprising an idiosyncratic survey of cross-cultural similarities, from tourists posing in front of landmarks to people hugging on sofas – a celebratory panorama of banality and heartbreak.

Rennó’s use of vernacular, found images reveals not nostalgia or novelty but puzzlement and alertness. Even with the one medium where she produces her own imagery – video – she actually embraces, as in the series ‘Turista transcendental’ (Transcendental Tourist, 2009–12), the format of the home movie, but twists it with simple interventions. As if a conceptualist had signed on for a package tour, we see a tracking shot along a vast Bolivian salt flat, displayed vertically; or a close-up of the stairs of an Aztec pyramid with frozen parts of the shot that linger as dizzying superimpositions.

In ‘Série Frutos Estranhos’ (Strange Fruits Series, 2006), found snapshots, displayed on small DVD screens turned vertically, hover midway between ordinariness and mystery: a man jumping into a pit at night, or a woman swimming, head down, underwater. Rennó treats the images to subtle animations and soundtracks: an owl hoots and a cricket chirps as the man moves his arms; mock whale cries accompany the image of the woman’s floating body. Abel Meeropol wrote the famous poem ‘Strange Fruit’ (1936) after he had seen a photograph of the 1930 lynching of two African-Americans, their bodies hung from a tree. In light of this, Rennó’s title may seem flippant, but thinking of her own creative impulses having often been prompted – like Meeropol’s – by images of pain and violence indicating injustice, they become emblems of the indissoluble ambivalence of the photograph itself: as if it were hooting and wobbling against the impossible task of adequately representing reality.