Ross Birrell & David Harding

Kunsthalle, Basel

Kunsthalle, Basel

We say something is hot; we say something is cool. Our critical faculties make use of temperature, metaphorically, almost imperceptibly often. It’s a way to diagnose style, and, as Susan Sontag writes in On Style (1965), ‘to speak of style is one way of speaking about the totality of a work of art. Like all discourse about totalities, talk of style must rely on metaphors. And metaphors mislead.’ Moving through Ross Birrell and David Harding’s exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, standing silently in front of the Glasgow-based artists’ films, sculptures, and light installations, I kept coming back to degrees of heat and cold – that is to say, I kept trying to take the temperature of the strangely measured, assured show that rose around me. If their exhibition felt cool to the touch – a kind of cold that burns – the artists, who have been collaborating since 2005, seemed to have predicted this in their title Winter Line.

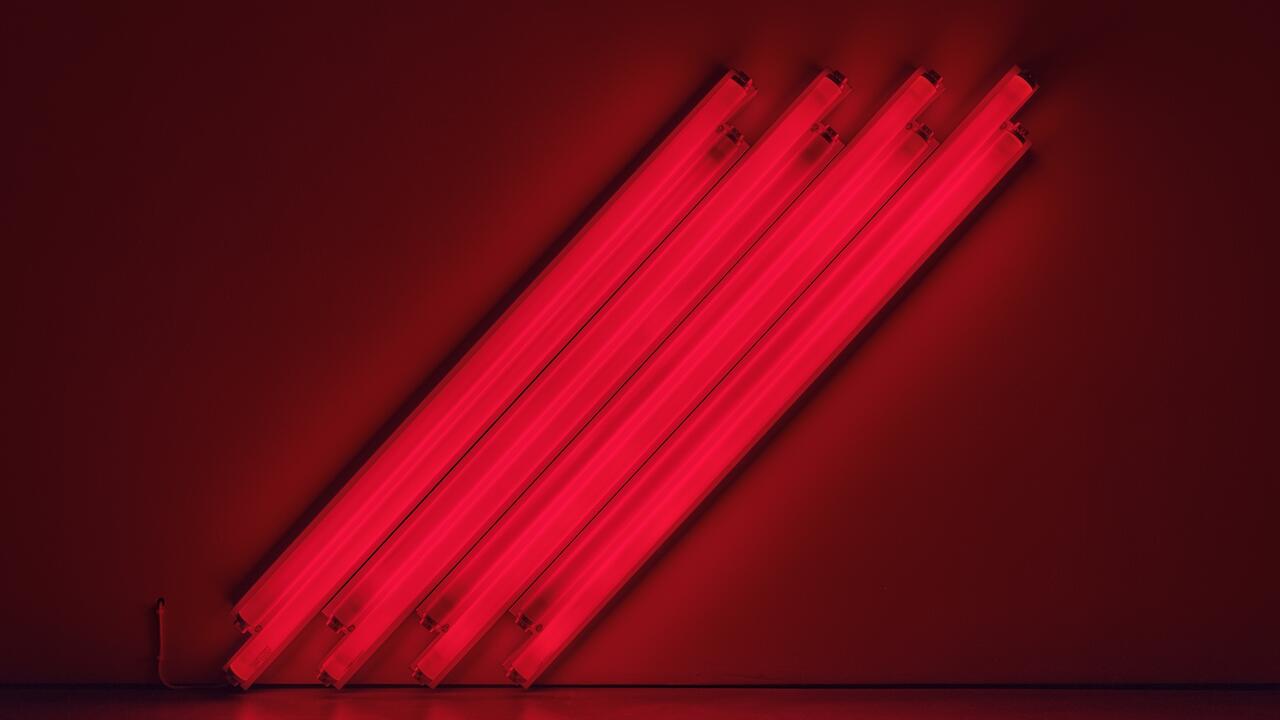

Soberly evocative in its plainness, the exhibition title refers not to a wintering white line – that cold horizon – but to war and its borders. The ‘Winter Line’ is the name of the military front in World War II, which moved through Italy. During the Battle of Monte Cassino in 1944, the Polish Allies were accompanied along that line by their mascot, a Syrian brown bear named Wojtek (you can’t make this up). Postwar, the bear was gifted to the Edinburgh Zoo, where Harding encountered it as a child. Wojtek’s image adorns the show’s poster, and is embodied in two pale, life-sized bear sculptures – Ursus Arctos Syriacus 1 and 2 (2014) – that occupy rooms lit a cool blue and a hot red respectively, via colour-gel-fitted skylights above. These luminous mosaics are works unto themselves, designed as visual correspondents to experimental notations and mathematical models of new music – which, with film and literature, forms a major pole of Birrell’s practice – from composers who worked under repressive ideological regimes.

The blue-lit gallery includes Ursus Arctos Syriacus 1 and a self-playing piano, illuminated by Nancarrow Sky (2014), after 20th century American Communist composer Conlon Nancarrow. The work’s glass panes fitted with gels in disparate blue hues – one aptly called ‘Ice’ – were arranged in line with the musical notation of Birrell’s Olinka Variations (2012). The following room – with its own bear, and a three-channel video installation – is illumined by Mural (Louange pour Messiaen et Mahmoud Darwish) (2014) and its 238 red-filtered glass panes. Mural’s title is taken from a poem by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, but also nods to French composer Olivier Messiaen, whose synaesthesia led him to ascribe a ‘stained glass window’ effect to his compositions. Despite the marathon index of avant-garde references, proper names, and deep intellectual and political wells from which Birrell and Harding drew, these rooms felt oddly spare, clean, cool, edited. One didn’t fall into their evocative referents like a pool; rather they held one back and alert, ever reticent, studious. In the artists’ performance of the old intellectual tradition, the old style, the viewer took it on, performing it herself.

Elsewhere, the allusions went on. Elegant, decisive works cited Franz Schubert (his 1827 Winterreise, an inspiration for the show’s title); Gilles Deleuze (a plywood-and-fabric wall, after the philosopher’s theory of the ‘fold’); Paolo Virno (a pale cast of his hand); and José Martí (whose poem supplied the lyrics for Guantanamera, here sung by singers in Guantanamo and Miami in two stunning film portraits). In French, a musical score is called a partition, and political borders criss-crossed Winter Line like so many musical bars: Guantanamo Bay; Israel-Palestine; Ciudad Juárez on the US-Mexican border; the ‘partitioning’ of war-torn Europe. The unabashed intellectualism and political investment on display in this artistic séance was mesmerizing, mysterious – and uniquely wrought. When contemporary artists mine such historical figures and their creative labours, a ‘poetic’ effect often results – something warm, too cozy with meaning. Here, that easy meaning remained elusive; instead, a formal quality reigned, a cold rigour not often associated with the allusive biographical material. It was cooling, finally bracing.