Balancing Act

Noemi Smolik visits the home of Inge Mahn and looks back on five decades of the artist’s socially-minded sculpture – in both town and country

Noemi Smolik visits the home of Inge Mahn and looks back on five decades of the artist’s socially-minded sculpture – in both town and country

‘First we’ll visit the Stallmuseum’, Inge Mahn says as she picks me up from the train station in her Jeep. I am an hour’s train journey northeast of Berlin. We drive along narrow roads, some of them unpaved. Our destination is the village of Gross Fredenwalde in Uckermark, a sparsely populated region, where Inge Mahn for the most part resides. The Stallmuseum – ‘Pigsty Museum’ – really is in a former pigsty, in the middle of the village. Previously dilapidated, the villagers wanted it demolished but Mahn took charge of the ruin and painstakingly restored it. The large central room now serves as an exhibition space.

For the inaugural show, Mahn invited the locals to bring in objects they thought were worth exhibiting. They brought old coffee grinders, saws, cooking pots, a mincer and old photographs that were shown in vitrines, on benches or simply on the floor. This was in 2012, and it proved an immediate hit with the residents. Then the objects were cleared to one side – they are still kept in the museum’s attic – to make way for ‘real’ art. This time, the show consisted of pictures the villagers had hanging on their walls at home. Once again, it was a success. More exhibitions followed, including photographs by Ute Klophaus and works by Hans-Peter Feldmann. The openings are always big occasions, followed by dinner for everyone. As Easter approaches, the preparations are underway for the next opening, a show of work by the painter Klaus Kehrwald (1959–2009) and a film by his widow Hanne Kehrwald.

While we are in the exhibition space, an older woman arrives. She takes care of the ‘reuse room’ that has also been set up in the space: people bring things they no longer need and take things they might be able to use. ‘People here are poor,’ says Mahn, ‘many are on welfare.’

In spite of the cold and rain, we go to visit the village’s 13th-century church. Like the pigsty, it had fallen into disrepair until Mahn took charge and restored it too. Today, religious services, concerts and Christmas parties are held here. The damp chill creeps into our clothes, but we go on to visit the shed next to Mahn’s home. The shed is a large space with a huge window offering a view out over the surrounding countryside. Its walls are lined with shelves crammed full of tools. In the middle of the room is an object that Mahn is currently working on: two simple stovepipes, their lower ends stuck in plaster plinths, their tops bending towards each other as if deep in conversation. Apart from this work, the room is almost empty. In a few days, the dinner for the opening of the Kehrwald show will take place here.

Back outside it’s still raining and the cold is becoming unbearable. My fingers are freezing; I can hardly feel my feet. But Mahn hardly seems to mind the cold at all. We arrive in front of a huge barn. The big door opens and at last I see other works by the artist – the reason for my being here. A circle of white chairs with water glasses placed on them; in the middle, a thin aluminium tube balanced atop a low table rotates horizontally like clock hands around the centre of the circle; crystals fixed to the ends of the tube touch the glasses, creating heavenly sounds. Next to this work are benches with angular litter bins beside them. In another room is a small dog kennel with a bowl in front of it and the remains of a chain, a tower with a bell and three brick arches that look like they might collapse at any moment. All of these objects – apart from the bowl, the chain and the bell – are made of white plaster, the material Mahn uses for almost all of her sculptural works. They look fragile, human somehow, striking me as slightly neglected living beings. Due to the cold, I almost feel sorry for them. I ask her whether she sees them as alive. Mahn thinks, then says: ‘Yes.’ But she doesn’t elaborate.

We are sitting in her kitchen drinking tea and looking through her catalogues. I ask if she’s pleased that her works were recently shown in the exhibition space of the art academy in Düsseldorf where she studied under Joseph Beuys, and that her work will be shown in June at Berlin’s Galerie Max Hetzler. After all, although she took part in documenta 5 in 1972 and has had shows at various Kunstvereins, she is hardly well-known. ‘Yes,’ she answers, ‘but what really makes me happy is my work here in the village.’ I want to talk more about her artistic career, but she keeps coming back to the exhibitions and encounters in the village. The preparations for future activities here seem to occupy her more than anything else.

When I get home, I peruse her catalogues. In a text by Mahn, I read: ‘“Bear ye one another’s burdens, and so fulfil the law of Christ.” (Gal. 6, 2) These words from the Bible are meant as a moral challenge.’ She continues: ‘Indeed, this wise teaching is based on a natural law. For when two burdens of equal weight press against each other with equal force, they cannot fall over. They remain standing because the simultaneous pressure they exert on one another creates a balance. The forces directed against one another cancel each other out.’1 These words stick in my mind. But I hesitate for a long time before including them here. After all, they are from the Bible – hardly an esteemed authority in the context of critical thought. But I feel I must quote them nonetheless, because they name the three principles that have shaped Mahn’s work. Principle 1: Accept the burden. Principle 2: Equate natural laws with the laws governing human relations. Principle 3: Seek justification for art in the social realm.

Principle 1

Burden

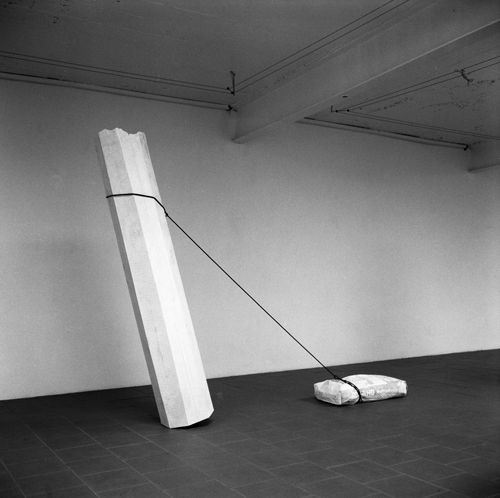

In most of the artist’s sculptural works, installations and interventions, the focus is on weights and load balancing; supporting and being supported – states that are of existential significance to all. Mahn summed this up wonderfully in her work An einander gelehnt (Leaning On One Another, 1992): two plaster chairs, each fabricated with only foremost legs, lean against each other back to back, maintaining an equilibrium. In the case of Säule, Gipssack ziehend (Pillar Pulling Plaster Sack, 1988), an octagonal plaster pillar with a broken top tips forward but held by the weight of a plaster sack that it drags along like a dog on a lead, it doesn’t fall.

7 Säulen (7 pillars) was the title of an installation by Mahn in 1983 at the Kunstforum der Städtischen Galerie at Munich’s Lenbachhaus. Although the seven giant pillars were made of solid plaster, their rough surfaces and fragility contrasted with the idea of the dignified supporting function they implied. They were askew, as if about to topple, and one already lay on the floor. They had failed as supports, and as a sign of this each one dragged a piece of the floor or ceiling with it, including some working lamp fittings with their cables showing.

As well as introducing an element of movement into architectural rigidity, this also evoked the collapse of a hierarchical system regulated by centuries-old architectural orders. What remained were pillars that recalled their function as supports and whose arduous existence as ruins gave them the air of human figures. Power and glory on the one hand, human-like fragility and failure on the other. An absurd situation in which – as so often in real life – comedy and tragedy are hard to distinguish. After the exhibition, the installation was destroyed – another affront to architecture’s claim to longevity.

Principle 2

Natural laws equal to laws governing human relations

An einander gelehnt, the above-mentioned work with the two chairs, is the best example of this equation. Only someone who can support others at the same time as receiving support is capable of maintaining balance. The pillar that drags a plaster sack behind it, preventing its own collapse but also entering into a dependence from which there is no escape, is also a fitting metaphor for many human relationships. And Stuhlkreis (Circle of Chairs, 2000), which I saw in the barn, recalls the circles of chairs commonly used in therapy where experiences and views can be exchanged. But for Mahn, leaving it at this would be too simple. She reinterprets this circle in mechanical terms, ‘making it speak’ via the rotating tube and the sounds thus created by the glasses on the chairs. Such equations between the laws of nature and the patterns of human relationships are a recurring feature in her work. In Anatomisches Theater (Anatomical Theatre, 1999) chairs balance like tottering human figures on legs of different lengths. In Roter Teppich (Red Carpet, 1980) a runner made of red coconut matting ascends the wall like a snake. And in the way they support each other, four dog kennels side by side, Hundehütten (Dog Houses, 1977), are more reminiscent of crouching, anxious puppies than architectural structures. As Mahn’s sculptures and installations slip endlessly back and forth between a level belonging to the world of human social relations and another that is subject to the laws of physics, the inanimate objects can be gripped by emotion as if they were living beings. This makes them amusing, but never ridiculous.

Principle 3

The justification of art via the social

When Mahn began working as an artist, the then-dominant school of minimalism attempted to eliminate all subjective references from art. From the outset, she wanted to rebut this. In 1970, while still a student at the art academy in Düsseldorf, she made a replica of a school classroom with benches and tables (Schulklasse). The benches and tables were slightly too small because Mahn, who was large as a child, had always experienced them this way. This gave the plaster furniture the kind of comic touch that can only be achieved by a subjective reference. It was this piece that Harald Szeemann saw during a tour of the academy; he decided there and then that he would show it two years later in Kassel as part of documenta 5.

Classrooms are the places where children begin to learn social behaviour outside of the family. It is this aspect that prompted Mahn to return to the motif two further times. In 2004 she filled a real classroom containing tables, chairs and a map of the world with hay – and let in some chickens. She called the work Dumme Hühner (Stupid Hens). One year later, in 2005, she scattered white chalk dust in another classroom in the same school and fixed a sign to the open door that said Betreten verboten (No Entry), the title of the installation. Some visitors went in nonetheless, and those who did bore the proof of their disobedience on the soles of their shoes and clothes in the form of white dust, spreading it to the rest of the building and out onto the school playground and the surrounding streets.

In 2003, Mahn realized TranspOrtale. Over the duration of the exhibition, she and her students (from 1993 to 2009, she was a professor at Berlin’s Weissensee School of Art) used wheelbarrows to transport one dismantled garden shed (plus a few trees) from the south of Berlin to the north, and another in the opposite direction. They did it with the help of the S-Bahn, advancing one station per day. The sheds met halfway at Unter den Linden station, where they were briefly reassembled on the platform before continuing their journey northwards and southwards respectively. The encounters and experiences during this absurd distribution project were unforgettable, says Mahn. And then I finally understand. For years and years, without making a big deal of it or associating herself with labels like ‘relational aesthetics’, Mahn has been cultivating an artistic practice rooted in interpersonal relations and their social context – or in fact ‘social sculpture’, the term coined by her teacher Beuys. This is also how she understands her activities in the village.

While I am writing this text, I receive an email from Mahn: ‘Easter was hectic with the opening at the Stallmuseum, 60 people stayed for dinner and 16 stayed overnight! Now things have calmed down again.’

Translated by Nicholas Grindell

1 Inge Mahn, ‘An einander gelehnt, oder aneinander gelehnt oder aneinandergelehnt’, in: Inge Mahn, Baustellen/Constructions Sites, Cologne 2011, p. 125