Sarah Conaway

Sarah Conaway’s best-known works, shown at the inaugural Los Angeles biennial in 2012, were produced on large-format Polaroid 55 film. Mostly black and white, their lush surfaces were occasionally charged with glorious colour: one of the still lifes, The Conversation in the Garden (2012), for example, portrays its subject against a velvety crimson backdrop. That film stock is now exhausted, so Conaway’s new works are all taken with a digital camera; they are antiseptically crisper in comparison. Her recent exhibition filled the two rooms of Barbara Seiler’s Kabinett-like gallery with modestly sized black and white photographs set in light-coloured mounts and dark frames.

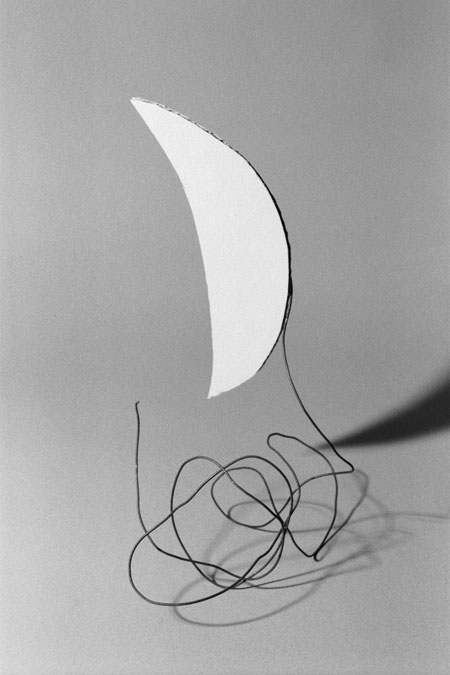

The images themselves are modest, too. Each is entitled Form, followed by a roman numeral (all works 2013). Form VII and Form VI were the first visible: the first shows two vertical lance shapes, each topped with a small circle. These elements have been cut from loosely woven light textile and suspended against a dark backdrop, to suggest a pair of earrings or two broad-hipped figures. The latter work is a similarly upright shape, out of which four strands of thread are looping, reminiscent of a dancing figure. On the other side of a doorway, Form VIII was their masculine counterpart: the same shape lying horizontally, forming a comedic moustache above the grimace of an undulating piece of string.

The show’s press release consists of a text written by Conaway that reads like a list, or a poem. It enumerates some of the artist’s ongoing concerns, among them: ‘grey area’, the planes of an image, how forms seem like other things, and ‘that one has an abdomen’. The text also elucidates some of the stuff we were looking at, such as thread, paper, Styrofoam, wire and brocade – which Conaway photographs in her studio against largely neutral backdrops. Her mundane props float like butterflies pinned in a collector’s cabinet, a gesture that simultaneously vivifies and kills. Conaway has spoken of her engagement with the ‘objectness’ of things; the Surrealist photographers who animated utilitarian objects are clearly borne in mind, not to mention the Surrealist idea of automatic art-making, which is equally mentioned in the text. The reference is not entirely straight-faced, for while artists like Man Ray treated household appliances – say, irons – as exotic and incomprehensible things, Conaway takes ‘female’ textiles and sexes them male and female.

With her restrained presentation, Conaway was running a high risk that the subtle points of friction in the works – like the scale of her subjects, which is so difficult to gauge – could be overlooked. She has departed from the lush presentations and larger prints that made her images easily comparable to those by artists more concerned with methods of photographic presentation (like, say, Elad Lassry or Annette Kelm), to focus instead on the what and the how. Conaway intends to fix the point at which things tip into connoting other things. Some of her subjects, like the loops of wire in Form XVII, seem determined to hang on to their own identities, but the handful of pale strings that cross Form IV teeters into an image of car lights captured by a slow shutter speed, while the three paper triangles perched on a bent corrugated cardboard hillock in Form II must be a copse of trees or yachts on a swelling sea. Of course, the transformation of object into symbol or likeness happens as much in front of the photograph as within it. The viewer has to invest belief in an image for it to amounts to more than the sum of its parts – for string and fabric to generate a face. Conaway’s work investigates how we interpret images, and how we not only observe but also add to what we see.