Stefano Arienti and Amedeo Martegani

Late last October, in an old apartment building in Turin, Stefano Arienti and Amedeo Martegani put on a show for the crowded courtyard below. It was a rear window, like in the Hitchcock film, but this time the clues didn't come from outside but from within. Luminous images neither facts nor evidence but merely bodiless lights emerged through a screen made out of a mosquito net.

Titled 'The Room of Informational Illusion' after the Douglas Adams sci-fi fantasy novel, the installation follows a method of visual presentation which they have developed together and which Arienti also used in the exhibition 'Cocido y Crudo' that allows them to set slides in sequence, to overlap them, and to regulate their timing.

Some of the photographs used were taken by the artists themselves, while others were more or less randomly chosen from an archive. The criteria behind their selection lies in their capacity to amaze despite the fact that they depict everyday scenes and their potential to prompt such questions as 'but, where is it? What is it? How is it possible?' In other words, to generate some kind of shift away from perceptive predictability.

The effect of astonishment is increased by the subtle movement of smoke coming from within the room, which blurs the image. A laser beam passes through the room and hits the mosquito net, emphasising the space's three-dimensional depth and thus denying the viewer the ability to look at a purely two-dimensional image. On the other hand it is a picture, indeed it is the reverse of the Brunelleschian box, with a projector replacing what should be our vantage point. The window-pane acts as a frame, whilst the sequence of images introduces the parameter of time; the smoke introduces motion; and the laser refers to the illusory quality of the image and the physical presence of the space. The result is a bizarre apparition, not especially spectacular but almost mundane, yet nevertheless capable of commanding our attention as if we had seen a ghost.

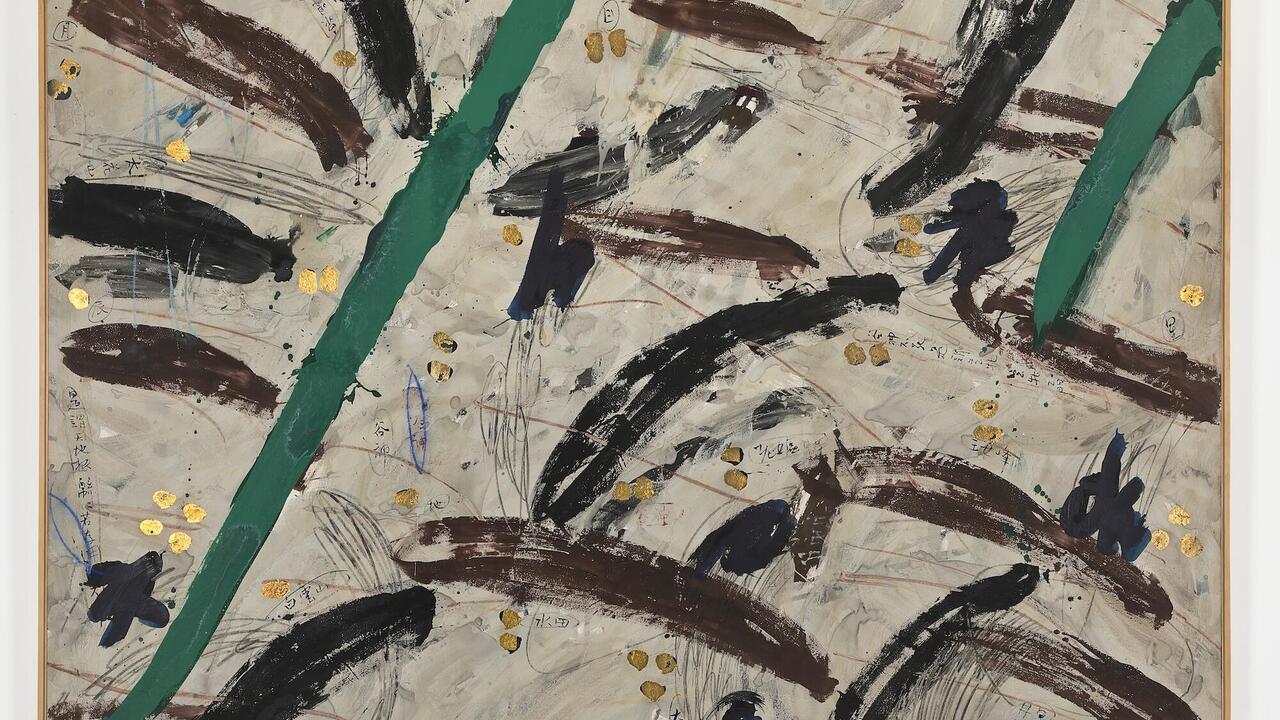

For many years, and through different methodologies, both artists have attempted to stir up the waters of imagery. Arienti has done so above all through his erasures: with a simple eraser or a scalpel he defaces comforting images, such as nature posters or Einstein's kindly smile. These minimal, repeated, obsessive gestures distort any background material. In the same way, Arienti used to fold the pages of comic books and transform them into sculpture. Martegani's equally warped computer-manipulated photographs are drawn from many sources, though mostly they are images he has taken himself. He designs and commissions tables and chairs with biomorphic irregularities; he uses watercolour to create astigmatically blurred landscapes, deriving from them a beauty made up of tiny monstrosities. His is a sophisticated and decadent oeuvre, and this is typical of his generation.

The years of noisy protest in Italy are long gone. Nothing burns, it just smoulders. After the painful experience of the years of terrorism, an entire artistic generation just over 30 looks at issues such as 'political correctness' with much suspicion. There are not many drugs, not much rock 'n' roll and little ideology for these disappointed, nice kids. Their game is as follows: present something appealing like a poster touched up with clay (Arienti) or something really vicious like a photograph of a little blonde (Martegani), tell lies day in and day out and thus earn freedom and impunity. Arienti and Martegani, like many others of their generation (both inside and outside Italy), have often been labelled as 'Neo-Conceptual'. Assuming this definition means something more substantial than it usually does, then particular attention should be paid to earlier Italian conceptualism rooted in the period just after the Second World War: the almost classical beauty of Lucio Fontana's slashes; the inevitable formal cleanliness, even in the filthiest Conceptual work, of Piero Manzoni; the elegance with which Pino Pascali drowned painting in irony. Approaching Arte Povera and, above all, the work of artists less connected to their materials and more oriented toward method (Giulio Paolini and Alighiero e Boetti), then the background of these two artists becomes clear.

In such work, images are closely connected to words, almost as if drawing from a Surrealist heritage rather than the strictly tautological trains of thought found in early Anglo-Saxon Conceptualism. Assertive and analytical proposals are replaced by optical and verbal tricks bent on disorienting rather than providing certainty. Two constant points of reference are always maintained: scepticism over content, which afflicts even the most rigorous of systems and gives it a labyrinthine sway; and beauty (now there's a dated term), the interest in the rhetoric behind the image, in things which seduce and astonish. This work bears within its genetic code a relationship of love and hate, desire and unattainability, toward the culture of images.