A Step Out Of Time

Sylvia Sleigh’s extraordinary ‘history pictures’

Sylvia Sleigh’s extraordinary ‘history pictures’

‘Fashion has a flair for the topical, no matter where it stirs in the thickets of long ago; it is a tiger’s leap into the past,’ wrote Walter Benjamin in his vignette-studded essay ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ (1940).1 Read the line quickly, add an extra letter, and suddenly the tropics are conjured. Benjamin’s ‘thickets’ become jungles, lush with almond-shaped leaves, green and waxy; through them a tiger skulks and stalks and leaps. The darkness (or lightness) of history emerges, humid and heated, between the carefully outlined leaves. Benjamin’s sentence has become a Henri Rousseau painting, as it were. Then the mind takes another leap, tiger-like, shaking the German critic’s sentence into yet another anagram, and those thickets of leaves become smaller, more domestic, but just as decorous. Now they curl from a pot, near a butterfly chair, a man’s pale, naked thigh. The fashions and fabrics filling the frame might be 1970s-era American approximations of Rousseau’s Africa – a different kind of herbarium, a later moment in history. How did this happen? You are now in a Sylvia Sleigh painting.

Benjamin continues: ‘This jump, however, takes place in an arena where the ruling class gives the commands.’ Fashion, flair, class, Rousseau’s collusion of representation and fantasy and fauna: all are present in and relevant to the figurative paintings of Sleigh, their weird and wonderful decorousness and their contemporary reading. See her 1981 work, Mitchell Fredericks by the Fountain, in which Fredericks – lean, nude, opaquely handsome – sits, knees apart, on a white lambskin rug thrown over some white marble, surrounded by potted plants, dark-green ivy and a fountain from which water pours, ever tastefully, out of the mouth of a lion. Or her titular 1962 portrait of the writer Francine du Plessix Gray, with Gray’s delicate, patrician profile and white button-down blouse carved elegantly against the downtown New York skyline.

Or consider Sleigh’s ambitious, oddly magisterial The Turkish Bath (1973), in which four New York critics and the artist’s young muse, all male and lithe, lounge naked against some hippie-bourgeois-looking textiles (Bauhaus, batik). The critics – John Perreault, Scott Burton, Carter Radcliff, and Sleigh’s husband Lawrence Alloway – are stilted and pensive, maybe nervous (not so much her husband). Along with them, Sleigh’s beatific, seemingly stoned muse, Paul Rosano, is pictured twice, once from behind, playing a lute, his tan lines glittering; once standing, his dark, tendrilled mane a feminine shroud parted perfectly, per 1970s personal styling, in the middle. Sleigh based the work on Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s 1862 painting, commissioned by Napoleon, of the same name – and names, one finds, are important in Sleigh’s oeuvre, in which they play social register, biographer and autobiographer at once. An erotic voluptuary of pale odalisques, Ingres’s circular canvas also offers a figure with her back to us playing a lute, though the musician here is spectrally female, her back as white and cold as marble.

As is often the case with Sleigh, there’s a witty note to her flexible, topical, warm homage: Ingres’s late work was inspired by the famous 16th-century letters of Lady Montague, in which she described her visits to a women’s bathhouse in Istanbul as the wife of a British diplomat. Sleigh’s painting replaces the interchangeable and sculptural Turkish concubines in Ingres’s Orientalist fantasy with skinny, 1970s New York men of letters, whose studiously rendered body hair and disparate shades of pale skin are embarrassingly real. Of The Turkish Bath Sleigh would later write: ‘I was inspired by [feminist art historian] Linda Nochlin to paint an “answer” to Ingres’s famous toads – I wanted to show how I felt women should have been painted with dignity and individuality – not as sex objects.’2 She also noted, plainly, lucidly, that she wanted, as a woman, the ability to paint ‘history pictures’.

‘History is representational, while time is abstract,’ Robert Smithson wrote in 1967.3 Sleigh herself once explained: ‘All our friends were abstract painters, and to be a “realist” seemed rather beside the point. I feel that what I want to express and communicate in my work can only be said in a figurative manner so I never defected from my course.’ Born in Llandudno, Wales, in 1916, she studied at the Brighton School of Art in Sussex, showed at the Trafford Gallery and the Kensington Art Gallery in London, and then made her mark in the 1960s and ’70s in New York, where she died in 2010. Her husband, who was also British, became senior curator at the Guggenheim Museum, New York: they met in an art history class in London when Sleigh was 27 and Alloway was 17, and in 1954 they married, settling in New York eight years later. There, her realist portraits of the city’s art world intelligentsia and beautiful, nude young men made her both a visual historian of her cultured, refined milieu and a seemingly retrograde iconoclast within it. For, at that time, abstraction gripped the world of contemporary painting – the singular, often underappreciated artists like Alex Katz, Alice Neel and Philip Pearlstein notwithstanding.

Yet Sleigh’s subtle anachronism did not only reside in her representational works, but in what they represented. A woman, she painted naked men more often than not. A feminist – she co-founded the women’s cooperative space SOHO20 Gallery in 1973 with 19 other female artists, and worked with the women-led A.I.R. Gallery extensively – she lovingly and repeatedly painted her husband and the seemingly traditional life that they led. ‘[H]e usually read to me, and I thought this is my idea of Elysian fields, to paint one’s beloved in a lovely setting out of doors in perfect weather – and either talk or be read to,’ she wrote without bourgeois embarrassment.

More often, though, Sleigh painted her husband and other subjects indoors, where their specific things document a specific place, class and age. See the bookcases heavy with the tomes of culture, the delicate vases of flowers, gorgeous and decorative fabrics, clean lines of Modernist furniture, desks for intellectual use, the flared legs of pants and spirals of frizzy hair, a certain orange-red Jorge Ferrari Hardoy butterfly chair, the ever-present potted plants. ‘Each thing is vulnerable,’ Joseph Brodsky writes, ‘Things are, in truth, the leeches / of thought. Hence their shapes – each one is a brain’s cutout – / their attachment to place, their Penelope features; / that is their taste for the future.’4

But questions of the temporal, of fidelity, are everywhere in Sleigh’s practice, which was concerned with the quotidian as well as the art-historical – note those ‘history pictures’ – and these questions flood her work’s reception even further now. In our present moment we like her paintings because, among other things, we think they ‘capture’ a time that we are nostalgic for – and in many ways they do. Nevertheless, these paintings and their maker were already anachronistic during their time. The nostalgia that arises (comfortably as well as uncomfortably) in current considerations of her work already existed in that work at its inception. Think of her contemporaries, painters or not: artists like Jo Baer, Lynda Benglis, Judy Chicago, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Eva Hesse, Lee Lozano, Carolee Schneemann, Joan Semmel and Joan Snyder. It’s not just that Sleigh’s work engages with and depicts a domesticity that even Chicago might recoil from, for Sleigh’s oeuvre demonstrates a serious commitment to her art practice; but her paintings themselves – their stylistic choices – look and feel weirdly docile, domesticated, earnest, sometimes naïve (the latter a charge also pointedly applied to Rousseau in his time).

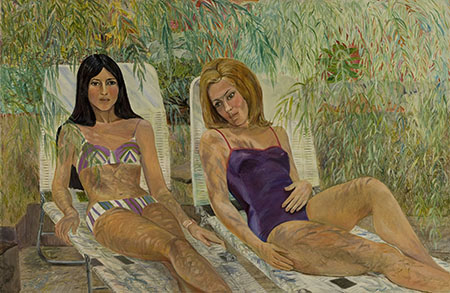

Despite Sleigh’s invested, and often now underappreciated, feminist activism, and her infamous male nudes, her work has none of the tension, strange pressure or alien opacity that we associate with the radical, the political, the ‘new’. And in spite of her famous and stirring group portraits of her fellow feminist art cooperative members (SOHO 20 Group Portrait, 1974, and A.I.R. Group Portrait, 1977–8), the lovingly intimate and painstakingly topical paintings are familiar, serious, affectionate, inoffensive, no threat at all. Even Sleigh’s weirder works – see the hair-like violet shadows of the leaves of the willow tree falling over the two female sunbathers in The Willow: Silvia Castro (1974), turning them into reclining she-wolfs – feel accidental in their strangeness. It doesn’t seem to be the artist’s point.

Such lucid approachability has led to a certain school of thought that notes, ironically, this feminist artist’s lack of commitment. The wonderful and astute critic Joanna Fiduccia recently described Sleigh’s reputation as that of ‘one of America’s least-offensive feminist artists’.5 Yet the offence the contemporary audience finds is not in her lack of feminism (Sleigh’s personal investment during her lifetime seems somewhat beyond our reproach) but in that her artistic ambition does not align with ours – or with what we expect from our artists. Her embrace of classical figurative painting and portraiture, her decorative style, which lacks the pathos and innervating brushwork and palette of her contemporary, Neel, all seem out of step with even her time, while simultaneously seeming so adept at documenting it.

‘The contemporary is the untimely,’ Roland Barthes observes, paraphrasing Friedrich Nietzsche, in the notes to his Collège de France lectures, which Giorgio Agamben cites in his essay, ‘What Is the Contemporary?’6 Agamben summarizes his stance thus: ‘Those who are truly contemporary, who truly belong to their time, are those who neither truly coincide with it nor adjust themselves to its demands. They are thus in this sense irrelevant. But precisely through this disconnection and this anachronism, they are more capable than others of perceiving and grasping their own time.’ Conversely, ‘[t]hose who coincide too well with the epoch, those who are perfectly tied to it in every respect, are not contemporaries, precisely because they do not manage to see it.’7 If it is possible, Sleigh fits both definitions. For her work, whatever you think of it, exists both alongside and apart from the continuum of contemporaneity that Agamben describes.

How so? We look to Sleigh’s work to see and thus experience a specific time, even as we feel discomfited by our own nostalgia, its fondness for surface signifiers and period décor. In this sense, Sleigh might be said to have coincided too well with her ‘epoch’ – her work could not transcend it. Yet, as she herself admits, she was out of step with her own time in her earnest adherence to realist painting and the cultured domestic. So when we approach her oeuvre for hits of nostalgia, we are, in fact, encountering the painter’s own. And it is here, in this doubling, where the deft, ineluctable strangeness of her body of work might be located, its peculiar handling and dismantling of time’s autonomy and progression. And if the strange brings the strange, consider Sleigh’s retrospective at Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, in the mountains of eastern Switzerland, in late 2012.

I visited one wintry Sunday in December – snow fell from the eaves as I walked the town’s deserted streets. Inside the small museum, I encountered Sleigh’s Zurich gallerist Jean-Claude Freymond-Guth. ‘The curator made cake!’ he said, smiling, and gave me a piece before I entered the cosy galleries. There, the unique exhibition design by textile designer Martin Leuthold shifted my attention from the odd domesticity attending the exhibition’s finissage. Temporary walls painted in bright, singular colours or cloaked in decorative geometric or floral fabrics held Sleigh’s paintings in the main hall. The choice aped the painter’s own works, in which graphic admixtures of textiles often underline the mostly pale, placid bodies that rest against them. The installation also pointed to St. Gallen’s textile tradition, and conjured the West African studio portraits of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé. But Benjamin’s ‘thickets’ of history were also evoked, in the form of the brightly patterned walls, decorous as leaves. By highlighting the small moments of pattern-like abstraction in Sleigh’s figurative works, pulling them out and letting them rise up like waves behind her smaller, body-filled paintings, the curators underlined the strange embarrassment that attends her steady, singular instinct for figuration so late in the 20th century. ‘There’s also abstraction here!’ they seemed to shout. So there was. Also joy.

1 Walter Benjamin, ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, edited by Hannah Arendt and translated by Harry Zohn, Schocken Books, New York, 1968, p. 261

2 All quotes by Sylvia Sleigh are from the Sylvia Sleigh papers at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Gift of Sylvia Sleigh and The Estate of Sylvia Sleigh Alloway

3 Robert Smithson, ‘Some Void Thoughts on Museums (1967)’, in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, edited by Jack Flam, University of California Press, 1996, p. 41

4 Joseph Brodsky, ‘New Life’, in So Forth: Poems, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1996, p. 12

5 Joanna Fiduccia, ‘Sylvia Sleigh’, in Kaleidoscope, issue 16, p. 28. (Full disclosure: I edited this essay)

6 Giorgio Agamben, ‘What Is the Contemporary?’ in What Is an Apparatus?: And Other Essays, translated by David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella, Stanford University Press, 2009, p. 40

7 Ibid.

The touring retrospective ‘Sylvia Sleigh’ is organized by Kunstnernes Hus Oslo, Norway; Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Switzerland; Tate Liverpool, UK; CAPC Musée d’Art Contemporain de Bordeaux, France; and Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Seville, Spain. The exhibition is on view at Tate Liverpool until 8 May 2013.