Stephen Willats

I’m a big admirer of the work of Stephen Willats. This frighteningly prolific British artist, whose career spans more than 50 years, has continually operated on the fringes of art-world circuits. His collaborative system of working and his studies of social groups, based around ideas of ‘feedback’ developed in cybernetics and black box theory, reverberate in much of today’s socially informed, participatory and process-based practice. (The Showroom’s conference ‘Signal: Noise’ in London earlier this year, where Willats’s conceptual diagrams provided the backdrop for discussions on how ‘feedback’ is deployed by contemporary cultural producers, is a case in point.)

MOT International, the small, fifth-floor unit in a imposing block in East London, was an appropriate location for such a show: the artist has used the tower block as a conceptual and (what he terms) ‘polemical’ device since the 1970s. ‘The Information Nomad’, Willats’s second exhibition at the gallery, comprised his signature diagrams.

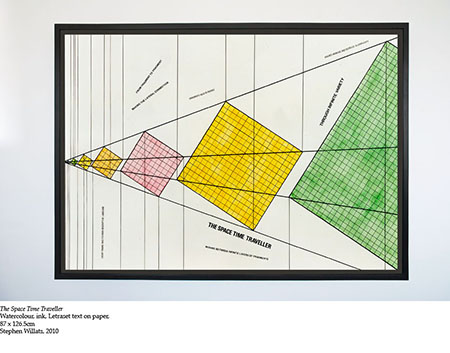

These have been at the core of his methodology since the 1960s, when he became interested in semiotics and information theory through practitioners such as Roy Ascott and Gordon Pask. Here, The Space Time Traveller and The Information Nomad (both 2011) expanded on ideas first put forward in the better-known Five Actions of Transformation (1998). This earlier work investigates how we perceive objects via a series of squares – developing from a simple black outline to a solid black box – through increasingly dense grids, with each square corresponding to a further variable such as presence, identity or behaviour. In The Space Time Traveller and Information Nomad, time is added to Willats’s perceptual equation and we are presented with an expanding field from left to right, within which are seven squares, showing how our understanding of objects or ideas progress ‘frame by frame’ into the future.

The notion of the future was developed with In the Beginning (2011). Willats has used photo-diagrams of this kind since the 1970s, allowing him to create visual, causal relationships between people, objects and places. Here, a couple with a young baby were asked about their hopes and anxieties: ‘this moment is a special moment’ / ‘people need to slow down a bit, that is our worry’. The sentiments formed part of a flow diagram with objects from the couple’s home (a teapot, a toothbrush and children’s toys) laid over images of the couple. Willats focuses on what we surround ourselves with, what he calls ‘life objects’, and how they reflect people’s engagement with the material world. But In the Beginning lacked any specifically contemporary imagery or terminology. Like many of Willats’s frames of reference and modes of presentation, the photo-diagrams were the product of a vastly different cultural moment; today, his aesthetic and sentiment can feel a little dated. Equally, in contrast to landmark works such as West London Social Resource Project (1972), which relied on a sustained and evolving relationship with a group of residents, surveying responses to a series of questions about their surroundings through distributed manuals and questionnaires, here the artist’s engagement with his subjects felt rather fleeting, the process of addressing the future somewhat rudimentary. The sense that art practice could shape the couple’s way of living – a central wager of Willats’s approach and one which West London Social Resource Project could stake a genuine claim to – seemed a big ask.

The main work in the exhibition, Signs and Messages from Suburbia (2011), covered one wall of the gallery and comprised a grid of more than 200 black squares, Willats’s ‘homeostats’. Amongst the squares were four projections roughly positioned at the top, bottom, left and right of the wall, corresponding to north, south, east and west London. The squares were interconnected by arrows, whose direction and subsequent flows across the wall were determined by rolling dice with numbers delineating different directions – a realization of the ‘randability’ and ‘probability’ Willats first explored in his early 1961 manifesto ‘The Random Event’. The four projections showed footage shot in the London areas of Kingston, Ilford, Harrow and Bromley, where the artist had documented road markings, signs or rubbish on Super-8 film. Here was a succession of public codes, the components of urban life.

Willats, always trying to de-author the art work, collaborated with a gallery staff member, Hana Noorali, and the writer Charles Arsène-Henry who visited the suburbs to collect sounds and record feelings expressed when there. Arsène-Henry’s texts intersperse the footage, adding a human presence – ‘the place is closed and empty’ / ‘a rush of lavender covers your eyes’ – to an otherwise dry sequence of documentary images.

Within the context of Willats’s substantial contribution to conceptual, site-specific and participatory practice, ‘The Information Nomad’ was somewhat formulaic – his examination of this particular set of people and places under-developed and rather fleetingly considered for such a meticulous practitioner. In contrast to iconic works such as Meta-Filter (1973–5) – a large computer, designed to construct a society based on agreement – or the interactive ‘Multiple Clothing’ series (1965–98), this group of diagrammatic charts felt insufficiently analogue and too static for today’s networked society.