Susan Howe

‘Tom Tit Tot’ was the title of the first-ever solo exhibition of the influential septuagenarian poet, Susan Howe. It is also the title of a slim volume of her ‘rectilinear’ poems (that is, poems that look like conventional poems) published on the occasion of the exhibition; an ‘unbound book’ of letterpress prints of Howe’s intertextual collaged poems; and a reading Howe did accompanied by a sound work by David Grubbs.

In Yale Union’s expansive gallery, the letter-sized prints of the collaged poems were inlayed flush under glass into an eight-metre-square table. Designed by Scott Ponik, it was hip-height and half-a-metre deep, a table that invited walking around the unbound book rather than a seated reading. The poems were arranged so as to honour the way Howe composes her poems in pairs of ‘facing pages’. From a low angle, the glassed poems appear to be pools of gleaming white on white.

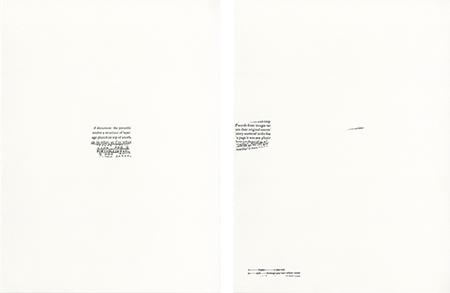

The ‘Tom Tit Tot’ poems are dense things, fragments of printed texts grouped in tight clusters that hover in expanses of white space. Howe will often cut a slab from the middle of a page, transforming the original prose into something like a lineated poem, then surround it with small fragments in other typefaces drawn from historic archives and works as diverse as those by Ovid, Robert Browning, W.B. Yeats and Charles Peirce, a book on the metaphysics of Baruch Spinoza and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and two books on Paul Thek. Howe lifts her variously applied title from Edward Clodd’s ‘Tom Tit Tot: An Essay on Savage Philosophy in Folk-Tale’ (1898).

Nowhere was Howe’s practice of cutting and taping the fragments together clearer than in an arrangement featuring a pile of thin strips of text, cut in half or thirds horizontally, leaving the tops of the letterforms visible enough to discern the words – but only just. Evoking a cutaway view of geological strata, these compositions suggest cutting down and through text and time, through the many pages and loose leaves Howe mines as the raw materials of her compositions.

For decades, Howe has made work inspired by her intuitive readings of books and archives, allowing the words to speak through her as if she were a medium. Howe facilitates these texts’ freedom to say what they will when loosed from the authority of their authors while encouraging them to say something else. ‘Tell us our names,’ one line reads. Another: ‘Out of a stark oblivion disenter.’ In her book Souls of the Labadie Tract (2007), Howe explained: ‘In Sterling’s [Yale’s Sterling Library] sleeping wilderness I felt the telepathic solicitation of innumerable phantoms […] I had a sense of the parallel between our always fragmentary knowledge and the continual progress toward perfect understanding that never withers away.’ This sensitive responsiveness to ‘telepathic solicitation’ should be seen in contrast to more masculine methods of plunder and scavenge: the mechanistic means of Jackson Mac Low or putting-your-words-in-my-mouth bravura of Ezra Pound. Howe thankfully resists tying her fragments together in neat packages but allows instead a productive ambiguity.

Howe says she had been asked to show the collages but has refused, considering them unfinished until they are letterpressed. The ‘Tom Tit Tot’ collage poems evince a vibrating instability while illuminating the combinatorial potential of series of words on the printed page. The letterpressing of the final collage fixes the text’s wildness, but seemingly only for a moment.

The exhibition was a moment of suspension, a view to the passage of work into and out of the book, but a very specific moment, post-printing and pre-binding. It comprised a book, a future book, a reading of a future book, and a book undone: in addition to the ‘Tom Tit Tot’ table, on one wall were selected printer’s spreads from an unbound copy of Howe’s book Frolic Architecture (2009). Where else but in this rogue kunsthalle on the periphery of the US, whose expansive print shop forms its core, could an exhibition this sensitive to the form and method of the book take place?

It could be argued that it is poetry’s time in visual art. The exhumation of Carl Andre’s poems suggests as much, as does the designer-artist embrace of works by poets in their florilegia-like publications, the frequent appearance of poem as artist’s statement, and the inroads poetry and its cousin, conceptual writing, have made in group exhibitions. But it is hard to imagine this exhibition happening at any mainstream institution. After all, curators have had nearly 40 years to recognize the significance of Howe’s work in the interzone between poem and visual art, and it hasn’t happened until now.