Tõnis Vint

When introducing the Estonian artist Tõnis Vint’s work, one could talk about his abstract geometry and sensual female characters; his background as a designer of stamps, record covers and theatre sets; or how he opened windows to both West and East within the Tallinn art scene of the 1960s, even in the closed society ofthe Soviet era. But his work remains little known. In fact, this retrospective at the Kumu Art Museum and its accompanying publication constituted the first thorough survey of Vint’s oeuvre. In addition to presenting a variety of his graphic art works – which fall somewhere between calligraphic exercises and scientific illustrations, realism and abstractionism – the exhibition’s related commentary opened upVint’s charismatic personality and his influence on the surrounding environment.

As ecstatic as I was to witness the rare and insightful selection of more than 200 pieces made between 1960 and 2000 – defined by the use of ink and gouache, consisting of mainly black, white and red elements, and referencing anything from American Pop art to Japanese culture – the most illuminating inclusion in ‘Tõnis Vint and His Aesthetic Universe’ was also the only audio-visual work: a film in which Vint appears as the narrator rather than the draftsman. This film not only illustrated the show’s portrayal of Vint as a personality-centred phenomenon, but also showed the vast range of his interests, from graphics and urbanism to his studies and teachings on visual sign systems.

Shown in the final room of the exhibition, Lielvarde Vöö (Lielvarde Belt, 1980) is a 20-minute experimental film made in collaboration with the Latvian director Ansis Epners, which introduces the artist’s views on ornament. In it, Vint traces, among other things, the connection between Baltic ethnic textile patterns and Celtic and Chinese symbolism. According to him, these traditional sign systems and folkloristic ornaments bear a close resemblance and contain typologies that can help us understand those cultures, and finally the world at large, through a single morphological language. Vint assigns a special conceptual capacity to the geometric symbols used in meditation – such as the mandala, or double disk – and believes them to carry messages from our ancestors.

Watching Vint present the ‘diagrams of the universe’, as he calls them, through the media of mitten patterns or the lines of the hand, accompanied by the Estonian composer Sven Grünberg’s otherworldly soundtrack of organ music and electronic sounds, the viewer gets an overview of the artist’s aesthetic universalism. Vint’s is a hermetic and all-encompassing theory – one that perhaps only he can totally comprehend. It embraces magical, religious and scientific elements, effortlessly uniting the early Modern period with contemporary knowledge.

While Vint’s aesthetic principles might remain unfamiliar to a broader audience, his idiosyncratic visions played a part in the Estonian resistance to Soviet assimilation during the national awakening of the 1980s. If not through the artist’s public proposals to redesign local symbols or urban space,which paved the way for the country’s independence in 1991, Vint’s ‘unofficial art lifestyle’, as it is called in the exhibition’s accompanying book, must have had a subversive effect at close distance. For Vint expressed his unique approach to the world not only through his art but also in his everyday life. As the book reveals, he has created a parallel reality in the confines of his own home and invited anyone interested to domesticate it with him.

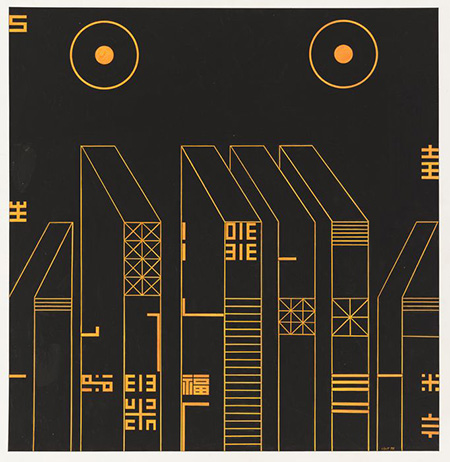

Since the 1960s, Vint has created and lived in an environment designed according to his own aesthetic system: first a white, Japanese-influenced apartment in the suburbs of Tallinn and later a completely black one in the centre of the city, defined by its tall bookshelves shaped like indoor skyscrapers. In addition to the unusual interiors and spiritual atmosphere of these places, what has made them particularly exceptional over the decades are their contents. Despite political censorship, Vint managed to secretly acquire international art magazines and radical philosophical literature. When the local intelligentsia and young artists heard of his collection of alternative knowledge, Vint’s apartment soon became a significant centre for the unofficial art life of others, too.

Outside official institutions, beyond the commonly accepted narrative, and in a time and space where reality, as it was generally experienced, set limits on people’s imagination, Vint had a special insight and a reformative mission: to view the world through universal aesthetics. Watching Lielvarde Vöö some 30 years later in Europe under the yoke of nationalism, his ideas could not feel more timely. Additionally, the fact that the exhibition of the now 70-year-old Vint’s syncretistic body of work was organized by a curator, an exhibition architect and a graphic designer, who are all in their 30s, speaks of its relevance today.