Tanja Roscic

freymond-guth & co. fine ARTS

freymond-guth & co. fine ARTS

Tanja Roscic’s exhibition Rose Colored Corner began in the antechamber of freymond-guth’s gallery with a bold untitled installation (all works 2014): a tawny velvet curtain hung from what looked like a battered, partially gilded, wooden door frame. The curtain was drawn from the top left corner to reveal the wall behind; on the right side a thick rusty chain draped from a protruding upper drawer into a larger one below, where it fell on top of a sisal-covered torso resting its head on a forearm, a tangle of orange straw for its hair. Studded irregularly, surreally, with diamond and oval shaped keyhole covers, the curtain’s lustrous velvet contrasted with the drab, pathetic half-figure, making for a striking, enigmatic opening statement.

Beyond this, the tone changed. The gallery divides into two adjoining spaces. While the contemporaneous exhibition Le Salon Particulier showed a selection of elegant mid-century furniture ‘from the collection of Angela Weber’ complemented by a decidedly tasteful hang of gallery artists, Roscic’s response was to show a collection of works that had even more in common with handicraft and ‘fireside arts’ than is usual in her practice. Though sewing, dyeing and appliqué have featured in her exhibitions before, they were frequently elements of powerful immersive installations that pulled no punches. Her solo exhibition with the same gallery at the end of 2011, for example, was a magpie-like gathering of neon lights, skeletal geometric wooden forms, airbrush painting, drawings and an abandoned car with a phantom hand still attached to the steering wheel (the gallery’s previous location was a former garage). So this restraint was a surprise, and disconcerting. Las Vegas, for example, belied the razzmatazz of its title. Behind the crosspiece of a large, thick-set wooden window frame a cluster of spindly fabric flowers – pink, yellow and magnolia – climbed upwards against a black backdrop, while a posy of dried flowers lay on the inside of the frame. Arguably the radiating petals could be read as fireworks over the Vegas strip but, for such a tasteful piece, it’s a stretch.

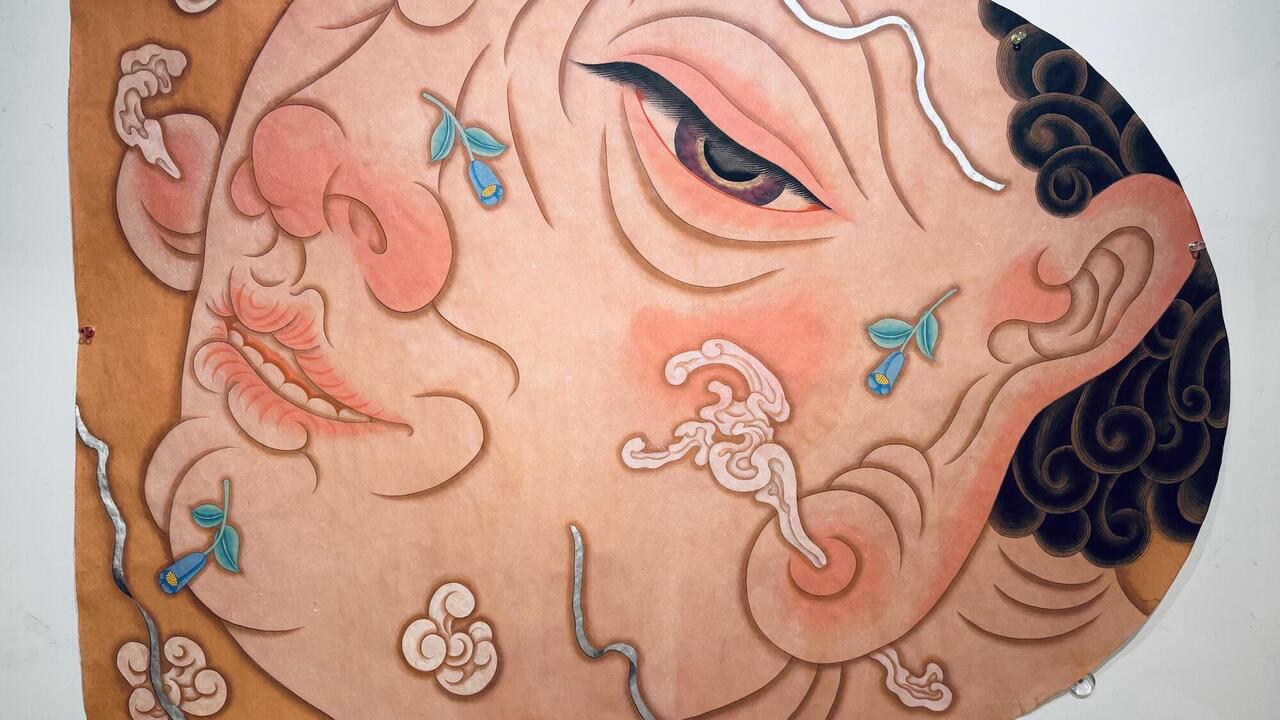

The recurring vocabulary of Roscic’s drawings hints at occult or folkloric traditions. This could be found in the exhibition but sounding at a low frequency. There was, for instance, a felt mask in the centre of an unstretched, unframed, untitled canvas nailed to the wall. More disembodied heads featured in another untitled work consisting of a pale sheet suspended within a rough window frame standing on the gallery floor. Lines of different coloured thread formed a skewed grid in the centre of the cloth over which two dark profiles were pasted. On the top ledge of the frame sat an empty soda bottle, functioning as a vase for a bunch of artificial violet blooms. A three by three grid of tie-dyed cloth squares tested how far amateur techniques could infiltrate the art space, but looked inexpert and out of place. The patterns – typically tie-dye and not particularly distinct – contained perhaps a sleeper reference in one of the media employed: shellac, the resin that seals nail polish so effectively that the wearer cannot remove it. Did this speak of maintaining prescribed appearances or fulfilling cosmetic norms?

Aside from the confident opening work, the predominant tone was of muffled expression. The repeated trope of the window to elsewhere and the persistent allusion to decorative arts as a form of control suggested an artist determined not to be at home in this salon setting. Roscic seems to be mounting her resistance to the faux-domesticity next door by knowing assimilation, hoping that her subversion of ‘feminine’ media would prove barbed enough to suggest alternative domestic possibilities. In truth, she needed to shout louder.