Tell Tale Signs

Olav Westphalen

Olav Westphalen

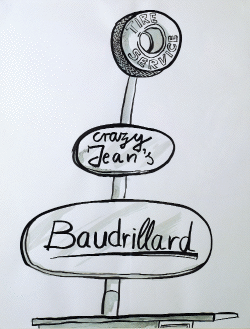

It might be the same world in which Michel Foucault owned the local trailer park, and Jacques Lacan managed a nearby bar and grill. A set of gouache cartoons by Olav Westphalen visualizes these never explored career paths as a series of brash steel-and-neon billboards. In a Trading Places-style switcheroo the usual suspects of post-structuralist theory finally get their come-uppance, absorbed into the same banal capitalist reality that they spent decades pulling apart.

Roadside Signs (1998-9) represents a take on the continued ubiquity of European critical discourse in American academia that only an artist born and raised in Hamburg, educated partly in San Diego and currently resident in New York, could have arrived at. The same could be said for Atlanta, Rhine and Prada (all 2001), in which Westphalen reproduces three of Andreas Gursky's most recognizable images in a similarly casual style. The perceived irreverence of these dashed-off homages immediately elicits a gratified smirk - we love to see masterpieces messed with - but also a host of more nebulous responses. The drawings may be the same size as the photographs on which they are based, but the ideological comparison that they imply is rather less direct.

Westphalen delights in low comedy, but his own brand of folk humour is invested with a sustained irony that transcends the straightforward coding of the one-line gag. His real interest is in what happens after that initial moment of recognition, when the distinction between joke and target falls away, and a cultural grey area stands revealed. This process is most clearly evident in Bruhaha (1998), a tortuously prolonged video in which the artist performs a lame stand-up routine on the perils of suburban living. Returning for an encore, he repeats the same set, this time backed by a sound recording of the first. By the time he returns for a fifth attempt his punchlines are all but lost in a Reichian echo chamber of competing voices. Westphalen's humour is nothing if not democratic - the joke here is on everyone, artist and audience included.

The fact that Westphalen studied under and collaborated with Allan Kaprow at the University of California is apparent not only in what makes him laugh, but also in his appreciation of the formalized and ritualistic elements of everyday life. Home Improvement (1993), for example, saw the artist line an office toilet with salvaged cardboard in an absurdist take on DIY interior decoration. In another early action, Nagelspende (Nail Donation, 1992), he attended the reopening of a Hamburg theatre. After offering his services to bemused patrons as a toenail-clipper he projected the resultant 'donations' on to the walls, using an overhead projector. The artist characterizes these activities as 'non-theatrical performances', unspectacular processes with open-ended or non-existent finales. Like Kaprow, Westphalen aims to blur the distinctions between different categories of experience, making space for a broader and less predictable range of interpretations. That his work is generally delivered without the tell-tale crutch of 'artistic' eccentricity makes this space that much easier to create.

The flavour of utopian idealism with which this methodology is infused has led to criticism of Westphalen's approach as a fetishized rehash of 1960s experimentalism that takes insufficient account of the extent to which contexts have changed. But the sheer mad-scientist gusto that he brings to each project makes it difficult to hold out against him for long. A series of home-made interactive machines and deadpan attempts at impossible tasks, while ostensibly aimed at the serious project of subverting or bypassing mediation, are straightforwardly engaging enough for the most solemn of observers to find themselves cracking a smile.

Take Walking on the Water (1993), in which Westphalen, with helium balloons tied to his back and polystyrene shoes on his feet, headed out across the Santa Barbara bay to see how far he could get. Having announced his intention in the local paper, he attracted a sizeable audience. Unfortunately, after nearly an hour of pratfalls and wipe-outs, he came no closer to his goal and was rescued from further humiliation by the remaining onlookers. Rapport Goggles (1992), a pair of interconnected visors containing lights that flash at frequencies determined by the breathing and speech of each user, are presented as a 'therapeutic device', but here again the technology employed is patently not up to the task.

Westphalen's affection for science, or pseudo-science, has also manifested itself in a series of tests and lectures. These tend to look and sound far more serious than is justified by their content, as if the mere appearance of objective rigour were more important than its genuine application. Erfahrungswerte (Research Evaluation), staged at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, in 1994, took the form of an extended 'study' of reflexology in which volunteers' feet were stimulated while their owners were interviewed on video. The resultant tapes, along with the plainly valueless 'findings' of the artist's research, were later presented and interpreted in a public talk. More recently, Essen in Schweden (Eating in Sweden, 1999) saw Westphalen, in ill-fitting glasses and nerdy wig, tackle the vast and complex subject of Swedish cookery, while managing, heroically, to keep a straight face throughout.

In his two-channel video Meet the Tigers (2001) Westphalen confronts a different aspect of Swedish culture by attempting to become a member of one of the country's major-league ice hockey teams. Struggling into the regulation uniform and safety equipment, he heads out on to the rink, but as the work progresses, his commitment seems to waver. At times he does his utmost to keep up with the game, while at others he appears uninterested, sulking in silence while his team-mates celebrate a goal. The stylistic mode of Meet the Tigers is similarly unpredictable, shifting without warning from documentary to slapstick. During a stint in goal Westphalen saves a shot by swallowing the puck. Later, he is unexpectedly bombarded with pillows.

Meet the Tigers demonstrates Westphalen's ability to visualize or embody several different viewpoints simultaneously, effectively denying us the chance to take sides. Wary of the implied rigidity of self-proclaimed political art, he prefers to approach an issue from more than one position, even when the results implicate him, contradict each other or do both at once. If Meet the Tigers is an essay on masculinity, violence, team thinking and the relative values of art and competitive sport, then what exactly is its conclusion? The moment we recognize Westphalen as playing any of the established roles of contemporary practice - the aesthete out of water, the abject, tragi-comic scapegoat, the shape-shifting subcultural infiltrator - he abruptly changes tack. Again, there is no guide to how we should react, no box to tick to confirm our understanding of the artist's 'message'.

E.S.U.S. (Extremely Site-Unspecific Sculpture) (2000-01) is at once ingratiating and intrusive. Designed to go anywhere, it never quite fits in. Everything about this vaguely functional-looking metal and plastic tripod, from its graceless design to its 'simply there' passivity, is vaguely irritating. Yet by resisting any identifiable theme other than its own impermanence, and by making no attempt either to harmonize with or to critique its surroundings, E.S.U.S. appears resistant to sustained attack. For the most part, objections simply slide off its polished surface like rain off a windscreen.

Conceived as a response to what Westphalen regards as the thoughtless dogma of site-specificity in current public art (an expectation that he compares to Greenbergian 'flatness'), E.S.U.S. goes as far as possible in the opposite direction. Built with the assistance of Randall Evans, artist and part-time NASA engineer, it can float on water (thanks to a lightweight, hollow body) and stand on any surface (with the support of its three telescopic legs). To ensure total self-sufficiency, it also boasts its own solar-powered halogen lighting system. It has appeared at a number of venues in New York and Stockholm, and fell foul of vandalism only when placed atop a Henry Moore bronze in a park in Gävle, Sweden, in 2001. Having unwittingly divided its audience into two opposing camps - those who approved of the renewed attention it attracted to the Moore, and those who perceived it as a tasteless affront to the master - E.S.U.S. was temporarily toppled.

It was perhaps with this kind of attack in mind that Westphalen recently began designing his own museums. Inspired by the same fun-park pop aesthetic as Roadside Signs, these so far include the Museum of Anaesthesiology in Tampa, Florida, and the Museum of Snorkelling in La Jolla, California. Each building is shaped to convey its subject with supreme literalness; so the Museum of Anaesthesiology, for example, is modelled on an outsize syringe. Envisioning the Museum of Olav Westphalen is a more problematic undertaking, but it's safe to assume that Thirsty 'Jack' Derrida's milkshake shack would find a home next door.