Their master's voice

The megaphones of Prague

The megaphones of Prague

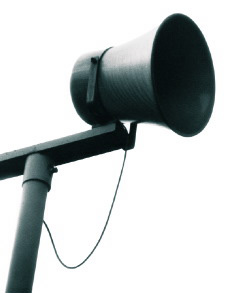

There are still a few, here and there, in squares such as Namesti Mim and I. P. Pavlova, reminding the passer-by with a jolt of the ways in which social space was controlled less than 15 years ago, of the anonymous voice of officialdom, projecting its designs into every corner of the city. The individual devices belie their function, coming in all shapes and sizes - anything but standard issue. In one respect they are more out of place here than in any other city, since the cultural history of Prague is dominated by an iconography of alleys, hideaways, dark labyrinths and places to get lost in, rather than of open spaces and boulevards hospitable to crowds.

The central figure of 19th-century Czech literature is that of the solitary wanderer, the chodec, who discovers the secret recesses of each of Prague's quarters. Come the 20th century, Franz Kafka drew the map differently, inserting this isolated figure within a geography of dread, showing how the reach of the authorities extended to every last passageway, culvert and piece of wasteland. The successive bureaucracies of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and postwar communism took possession of the city of the alchemists and seized the right to speak for it, with a disembodied voice that's the ultimate expression of power and whose interests are dislocated from those it claims to represent - the megaphone is the icon of the nomenklatura, political ventriloquists who speak not with the people but in their stead. At the same time this mechanization of the voice is intrinsic to a more clandestine tradition associated particularly with the area around the castle: with a belief in the golem, with a desire to create automata, with the dream of assembling a creature from disparate body parts.

This rather more sinister genealogy was given official sanction by the paranoid collector and Prague-based 16th-century Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, who employed teams of magicians and who was delighted by any apparatus that simulated and displaced the human. Its artistic correlative can be found in the paintings of the Milanese artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo - sent to Prague in 1570 to design an elaborate pageant - whose output was devoted to curious amalgams of objects that mimicked the lineaments of the human figure.

Today the electric wiring has been torn from every last speaker still in position, but it makes no difference: the megaphones of Prague are forever earthed into a history, a memory reservoir, a cultural power supply. Easier to remove than the more obvious memorials to a future that never happened, they are nowadays mostly ignored, immobile, gently swaying with each change in the direction of blustering winds.