Thomas Locher

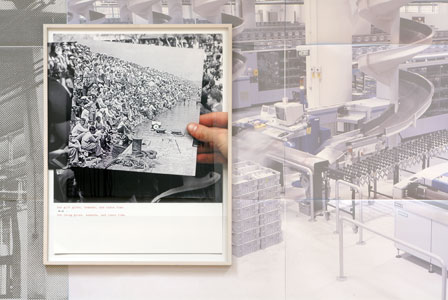

Photographs of empty production facilities, of people with boxes of screws. In one image the clock on the wall says ten to 12, but it could be day or night; in another an orange industrial robot, mighty and monumental, signals readiness. For this exhibition entitled ‘Erscheinungen’ (Apparitions) Thomas Locher has plastered the walls at Kunstverein Heilbronn with large-format photo wallpaper. It shows hi-tech factory halls, in which everything is clean and well ordered. Other images framed and mounted onto these backdrops, in contrast, portray people in comparatively private situations, documenting a range of transactions that clearly take place in the world of the wealthy and the beautiful: a couple dining in a luxury restaurant; a man of whose face we see only the fat chin above his tie, and in whose hand rests a writing implement – is he giving autographs or signing cheques? Whatever the case, hands stretch out eagerly towards him from all sides. Locher accentuates the particular nature of these scenes by placing accompanying texts within the frames, thus even more clearly setting the actions in these images apart from those in the industrial wallpaper scenes.

The texts introduce a degree of complexity to the work that dispels any idea of these images simply illustrating a black-and-white model of society: the wealthy and the wage slaves, the exploiters and the exploited. Although on both visual and textual levels Locher focuses on the themes of work, money and ownership, he does not refer to simple causal connections. Seduction, excess and waste are also brought into the equation. In one passage quoted from Jacques Derrida’s Given Time I: Counterfeit Money (1992) the peculiar character of gift-giving is elucidated: as with other forms of exchange, the giving of a gift is based on the assumption of receiving something in return, yet the distinction is that it does not demand it immediately, just anticipates and waits for it. ‘The difference between a gift and every other operation of pure and simple exchange is that the gift gives time’, we read at one point. And elsewhere: ‘A moderate, measured gift would not be a gift.’

Just as Locher’s images should not be perceived independently from the texts, so it is also impossible, the artist would appear to attest, to separate the emotional, cultural and religious scenes depicted from the economic sphere in which they take place. Gift-giving is an exchange, but it is much more than a business transaction; conversely, business would be unable to thrive without occasional irrational or spontaneous actions. Language, too, reflects this ambivalence between imagination and finance: one can ‘speculate’ in thought, but also in stocks. Psychoanalysis, whose theories Locher has studied extensively, has always focused on the links between belief, money and libido. And it was Karl Marx who stated: ‘Credit is the economic judgement on the morality of a man’ – a phrase used by Locher for a work in his 2006 exhibition ‘Die Rechnung geht nicht auf’ (It Doesn’t Add Up) at Reinhard Hauff Gallery in Stuttgart.

The quotation prefaced an informal painting consisting of a few casual eruptions of colour. Locher has included a similar splash-and-splatter painting in the Heilbronn installation, as though this explosive, dynamic mural was intended to underline one of the central motifs of his conceptual method: the deconstruction of the supposedly self-evident whose inner contradictions often go unnoticed because everything – on the outside at least – appears coherent. Locher walks the thin line between plausibility and paradox, between probable arbitrariness and semantic contingency, a path that takes him beyond the point where language gets stuck in its own conventions and pictures lose themselves in illusion or fantasy. Locher sees his art, he once said, as a dialectical process, ‘the aim being to sublate and overcome this dialectic’.