The Threat to Freedom of Expression in Japan

The closure of part of the 2019 Aichi Triennale reflects a broader climate of aggression, censorship and nationalist revisionism

The closure of part of the 2019 Aichi Triennale reflects a broader climate of aggression, censorship and nationalist revisionism

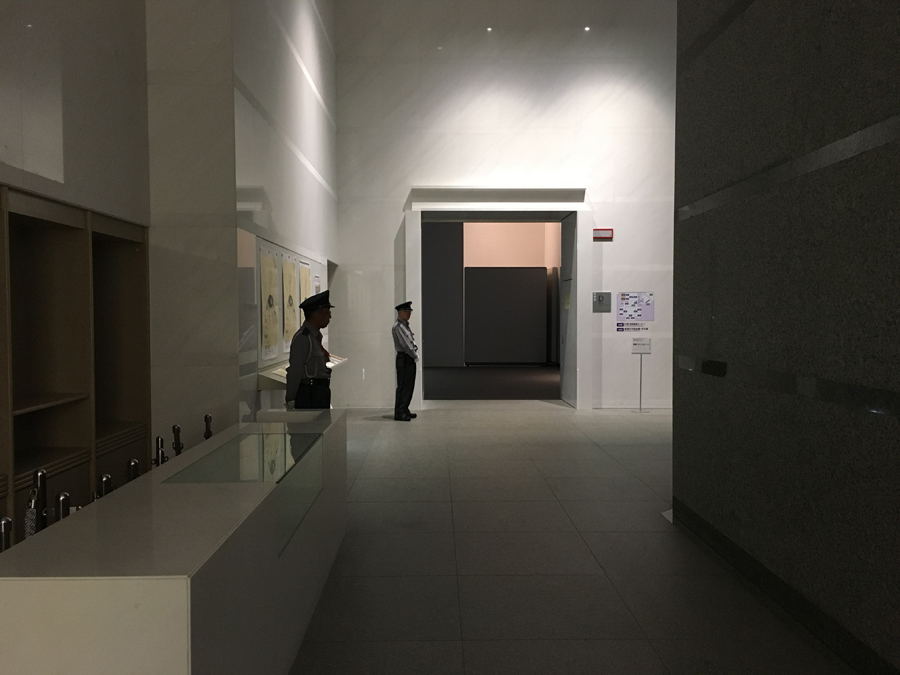

There are so many backstories to the story of Aichi Triennale 2019’s disastrous opening weekend that it’s hard to know where to start. On 3 August, two days after the show opened, an exhibit bringing together more than 20 works that had been censored in recent years at public institutions in Japan, entitled ‘After “Freedom of Expression?”’, was itself effectively censored. Only the Triennale organizers insist it wasn’t censorship. They justify the decision to shut down the exhibition, the entrance to which is now blocked behind large partitions, as an emergency response to the hundreds of angry phone calls – many of them aggressive in nature – that overwhelmed the Triennale office in the days following the opening, as well as a fax threatening to burn down the venue, sent 2 August. (The sender of the fax has since been apprehended.)

Yet, the extremity of the public response and the alacrity of the decision to shut down the exhibit were also likely influenced by statements made by local and cabinet-level politicians including the mayor of Nagoya, where the bulk of the Triennale is located. Calling for the exhibition’s closure, Mayor Takashi Kawamura said that the works in ‘After “Freedom of Expression?”’ – namely, Korean artists Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung’s Statue of Peace (2011), a sculpture of a young girl that addresses the legacy of the Japanese military’s ‘comfort woman’ system, which pressed women and girls from occupied territories including Korea and Taiwan into sexual slavery during World War II, and pieces by several Japanese artists incorporating the image of the wartime head of state, Emperor Hirohito – ‘trample on the feelings of the Japanese people’. Meanwhile, echoing both war- and Trump-era rhetoric, right-wing Twitter trolls attacked Triennale artistic director Daisuke Tsuda for being an ‘anti-Japanese Leftist’ and told him to get out of the country.

On 5 August the governor of Aichi Prefecture, Hideaki Omura, who is also head of the Triennale’s organizing committee, took the extraordinary step of publicly criticizing Mayor Kawamura for infringing upon Article 21 of the postwar constitution, which guarantees freedom of expression and prohibits censorship, but it was too little, too late. After all, Omura was involved in the decision to close the exhibit along with Tsuda. That Governor Omura could or would not think of alternate emergency measures – from hiring more operators to beefing up security – confirms that there is minimal political clout for defending protected speech when it runs afoul of the dominant agenda. This comes on top of long-standing proposals by the ruling Liberal Democratic Party to refashion the 1947 constitution in a more nativist and potentially authoritarian bent, including restoring the emperor as head of state and restricting rights and expressions that interfere with ‘public interest and public order’.

There is no mincing words. The closure of ‘After “Freedom of Expression?”’ is an absolute crisis for art and free speech in Japan, and how people respond to it may set the parameters of expression for years to come. If the exhibit made visible the censorship regime under which artists and curators are already operating at Japan’s public institutions and organizations, its closure raises the spectre that all large-scale art activities will be ruled for the foreseeable future by self-censorship, in order to secure government funding and corporate sponsorship. More chillingly, it emboldens extremist elements to use violence to silence others.

Ironically, the Triennale has in some way become a stronger exhibition thanks to the closure of ‘After “Freedom of Expression?”’ Works confronting the nature of Japaneseness and Japanese society have taken on added urgency and push back at right-wing politicians’ invocations of essentialist monoculture: from Koki Tanaka’s multimedia installation Abstracted/Family (2019), which looks at the lives of mixed-race Japanese people, to Kyun-Chome’s videos presenting the voices of those transitioning between genders and Miku Aoki’s immersive mixed-media installation, 1996 (2019), combining references to cloning, artificial insemination and a eugenics law allowing the forced sterilization of those with genetic disorders and handicaps that was not abolished until the work’s titular date.

One of the most powerful displays in this context is Mónica Mayer’s The Clothesline (1978/2019), which invites participants to write anonymously about their experiences of sexual oppression or violence on pink cards that they then attach to a clothesline-like structure for other visitors to read. On view at the Nagoya City Art Museum, this work is long overdue in a society where gender inequality is still heavily entrenched. The day I visited, on August 7, there were statements about being molested in adolescence, being groped on trains, harassed by teachers, pressured into uncomfortable situations by bosses, raped. There were statements about being told not to bother going to university, not to bother going into academia, not to bother trying for a career. In Japan, as elsewhere, these experiences are unfortunately all too common, but watching a table of teenage girls intently filling out their pink cards, and seeing schoolboys engaging as well, I got a profound sense of the work’s liberatory potential.

To that extent I sympathize with the Triennale’s chief curator, Shihoko Iida, who told me she would not quit so long as any artist wanted their work to remain on view. This is undoubtedly an important exhibition for local audiences to encounter at this very moment. But what compromise, if any, is acceptable? Mayer’s Clothesline, which has been installed in places ranging from Mexico City to Medellín and Washington, D.C., is a reminder of the utter misogyny behind the current Japanese government’s denials of the military’s involvement in the ‘comfort woman’ system, its use of victim-blaming and gaslighting techniques to discredit survivors who have come forward to testify about their experiences, and its purging of the topic from middle-school history textbooks. (At present, only one textbook on the market, representing 0.5 percent of sales, makes mention of ‘comfort women’.) We cannot allow attempts to speak critically about the actions of the former Empire of Japan or the policies of the current Japanese state to be relativized as ‘hate speech’ or ‘propaganda’, as the trolls would have it, and repressed as taboo subjects. (Following Korean artists Minouk Lim and Park Chan-kyong on opening weekend, Mayer is among a group of artists who have since asked for their works to be held from view until ‘After “Freedom of Expression?”’ is reopened.)

An earlier draft of this essay began by recounting the Women’s International Tribunal on Japanese Military Sexual Slavery, organized in December 2000 by women’s groups led by Violence Against Women in War-Network Japan (VAWW-NET). Conceived as a symbolic extension of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East that followed World War II, the Women’s Tribunal presented testimony by 64 former ‘comfort women’ and other witnesses before a panel of international judges and a 1,000-member audience. The guilty verdict went right to the top of the military hierarchy: Emperor Hirohito himself, who was famously spared prosecution by the American-led Allies as the lynchpin of their realpolitik for postwar reconstruction.

From the vantage point of today’s Japan, this is explosive material – it has the makings of a fantastic art project or the vision of a radical filmmaker. That such a project seems almost unthinkable now shows how far right the climate has shifted. As with the Aichi Triennale, the small archive and resource center established in Tokyo in 2005 to house the records of the Women’s Tribunal, the Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace (WAM), has endured harassment and a bomb threat, sent in 2016. But when I went there after my return from Nagoya, it did not look like it was under siege. It was a welcoming environment where visitors conversed with each other and the staff in a mixture of Japanese, Chinese, Korean, English. It was a place open to knowledge and inquiry, past and future. Its continued existence is testimony to the fragility of democracy in Japan.

The idea that art should not be political has been turned into a political tool for excluding unwelcome expressions from public venues in Japan. But art is the frontline in debates around free speech precisely because it creates space for questioning values and challenging historical assumptions in public. Without this, art and its institutions devolve into an opaque aesthetics of power. And without the possibility for incorporating critical voices, all the art festivals that have proliferated across the archipelago in the past two decades – which come packaged with hedonistic sidebars of local cuisine, crafts and products – will be exposed as so many empty frameworks for extracting money from tourists and pumping capital into regional economies. Information available in Japanese on the Aichi Triennale website estimates that the 2016 edition brought some JP ¥6.3 billion yen (around US$60 million dollars) into Aichi Prefecture, against JP ¥1.2 billion yen (US$11.5 million) in expenses. As with many such events on the international art circuit, participating artists must be aware their work will be instrumentalized to a degree. But could they put up with it if they felt such events lacked any integrity?

This is no time for looking on passively. Japanese artists, and the Japanese art scene as a whole, must lead the way in taking action.

NOTE: As of writing, the following artists have asked for their work to be withheld from Aichi Triennale 2019 in protest of the closure of ‘After “Freedom of Expression?”’: Tania Bruguera, Pia Camil, the Center for Investigative Reporting, Regina José Galindo, Claudia Martínez Garay, Dora García, Minouk Lim, Mónica Mayer, Reynier Leyva Novo, Park Chan-kyong, Pedro Reyes (as curator), Ugo Rondinone, Javier Téllez.

Yuka Okamoto and other members of the organizing committee of "After 'Freedom of Expression?'" speaking at a press conference at the Aichi Prefectural Government Office on 6 August. At the press conference, the organizing committee presented an open letter to Aichi Prefecture governor and head of the Aichi Triennale 2019 organizing committee Hideaki Omura asking for an explanation of how the decision was taken to close the exhibition. Photograph: Andrew Maerkle