Today is an Example

Praised by T.S. Eliot and best friends with Harry Smith, Lionel Ziprin was a mystic and poet whose archive is a source of fascination for many contemporary artists, especially Carol Bove, who now houses it in her New York studio

Praised by T.S. Eliot and best friends with Harry Smith, Lionel Ziprin was a mystic and poet whose archive is a source of fascination for many contemporary artists, especially Carol Bove, who now houses it in her New York studio

Sequestered in a room-sized safe in the bowels of Brooklyn is a collection of artifacts – books, boxes, manuscripts, tracts, paintings, prints, recordings, a ratty old rocking chair – that once belonged to the New York mystic Lionel Ziprin. It comprises a lifetime’s worth of accumulation, by a figure whose legend is little known. Before his death in 2009, Ziprin was a secretive oracle of the Lower East Side, with a wealth of knowledge that ranged from the cryptic to the rabbinical to the supernatural and back again. Some of his belongings are religious documents that date as far back as the 17th century. Others align with postwar American forays into formative psychedelia and realms of the occult. Much of it is esoteric; all of it is mysterious, suggestive or at least a little bit otherworldly and strange. ‘It didn’t just feel like moving materials,’ said the sculptor Carol Bove, whose studio in the outer reaches of Red Hook was enlisted two years ago to give the collection its current home. ‘It was an event.’

Among the makers of the materials, closely guarded by Ziprin during his lifetime and suspected to hold special powers still, included Jordan Belson, Wallace Berman, Bruce Conner, Diane di Prima, Allen Ginsberg, Angus MacLise, Harry Smith and Joanne Ziprin – a litany of artists whose wanderings between disciplines and disparate strains of thought defined a subsection of the 1950s and ’60s countercultural scene. From Ziprin, artists attained access to deep teachings of Kabbalah and all manner of gnostic doctrine. (An early meeting with Harry Smith included communion over The Great Beast, John Symonds’s 1951 book about Aleister Crowley.) From the artists, Ziprin gained an audience for his intensely networked and wildly idiosyncratic mind.

‘He was this mythical figure, referred to with a combination of veneration and fear,’ said Philip Smith, an independent scholar who met Ziprin late in his life, while researching the many extraordinary orbits around the work of Harry Smith. After seeing singular Harry Smith films such as Mirror Animations (1957) and Heaven and Earth Magic (1957–62), Philip Smith fell deeply under the polymathic artist’s sway. (The muse with whom he shares a surname is of no relation; that it seeds confusion is somehow fitting for the subject.)

Philip Smith delved deeper into Harry Smith’s experimental movies and developed an eye for his paintings, many made as visualizations of music by Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk. He learned about his visionary, systematic collecting of colloquial art forms, ranging from paper aeroplanes to Native American string figures to elaborately painted Ukrainian Easter eggs. He listened to his best-known work, the Anthology of American Folk Music which, since its original issue on six LPs in 1952, ranks among the most consequential cultural offerings of any kind of the 20th century.

Though it abounds with seminal characters, the story of Harry Smith could not be told without the foundational presence of Ziprin and his wife Joanne. In the early 1950s, Smith knocked on the Ziprins’ door after first making his way from California to New York, having been given the address by a fellow wanderer who lived in the middle of the country and later wrote a book about UFOs. They bonded, and lived and worked together for years.

‘I have no memory of Harry Smith other than being terrified by him,’ said Zia Ziprin, Lionel’s daughter and the executor of his estate. ‘Now I’m aware of what a huge influence he had, not only on art but also on film and music, but as a child I used to take my sister and hide in the closet when he came over, which was quite often.’

Known for their shared cantankerousness as much as their brilliance, Ziprin and Smith – new friends in the midst of much hermetic theorizing and experimental art-making – helped start an unlikely commercial endeavour in the form of a greeting-card company called Inkweed Arts. At the helm was Ziprin’s wife, Joanne – a guiding presence and gifted illustrator whose drawings’ wry and winsome charms played into an Inkweed aesthetic divided between biting wit and metaphysical weirdness that was remarkably cool for its time. A ‘happy anniversary’ card shows a bruised boxer standing dizzily but lovingly next to his wife, with the message: ‘So glad we made it.’ Another card, teeming with striking abstract illustrations, reads: ‘Stop doodling! Be my Valentine.’ Others made pioneering use of 3d printing techniques to be peered through disposable glasses and, in a draft for a card whose purposes are unclear, an etched self-portrait on scratchboard of Harry Smith as the devil.

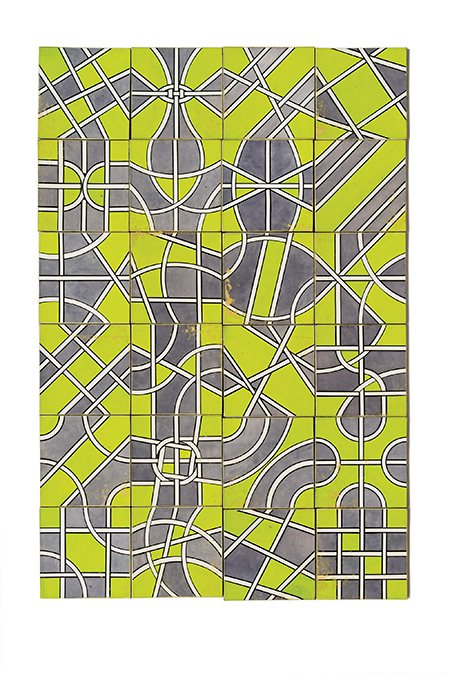

The original incarnation of Inkweed sold its playful and arcane cards in stores across the country from 1951 to 1954, but untenable production costs and ramshackle business practices necessitated a change in command. A few years later came Qor Corporation, an enterprise devoted to the design of abstract patterns to be adhered on mylar sheets to wall tiles and surfaces of various ornamental use. The designs, envisioned mostly by Harry Smith and Lionel Ziprin, could be customized, moved around, interconnected – enlisted to broadcast secret meanings in the midst of their duties as ‘mere’ decorative art.

Prototypes from the project, unseen by anyone except for the few who knew of the fledgling company’s aspirations in the early 1960s, featured in a show last year at Maccarone Gallery, New York: ‘Qor Corporation: Lionel Ziprin, Harry Smith and the Inner Language of Laminates.’ Curated by Bove and Philip Smith, it served as an addendum to an exhibition of Bove’s own work at the same gallery. The announcement for the concurrent shows read: ‘These presentations share a common denominator, their close proximity conjuring up the metonymic measures and enigmatic core of the uncontainable and ever-shifting nature of the abstract gesture.’ The use of historical materials to conscript different philosophies and systems of thought was not a first for Bove but, in ways hoped for by all involved, it marked a coming-out for the vast, teeming and as-yet-untapped Lionel Ziprin archive.

‘I am not an artist. I am not an outsider. I am a citizen of the republic and I have remained anonymous all the time by choice.’ So wrote Ziprin in one of many declarations of purpose and intent. He was prolific, and especially with words. ‘He’s a major 20th-century poet who’s basically unpublished,’ said Philip Smith. ‘Even if you want to ghettoize him with the “Beat” rubric, which is inappropriate but you can, he’s easily the peer of any. There are major Beat poets who are nowhere in the vicinity of Lionel. And there’s a massive amount of this stuff that no one has ever seen.’

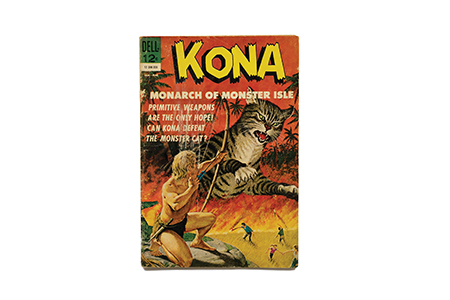

In response to one of just a handful of poems he ever published, Ziprin, while young, received a letter of praise from T.S. Eliot. Beyond that, his literary record is scant, known mostly by way of his work in the early 1960s as a writer of comic books (for the series Kona, Monarch of Monster Isle, which laced Kabbalistic numerology into tales of a heroic caveman’s adventures) and, most notoriously, a 1,000-page poem titled ‘Sentential Metaphrastic’. A short excerpt of this epic masterwork was published in ‘The Psychedelic Issue’ of the multimedia magazine Aspen, in 1971. Among its lines:

Today is an example.

I cannot relate one to the other though, because

primarily I am a risk.

The perspicacious write me off.

And those who do not, those who don’t – what of

them?

Whose burden do they carry?

Wrangling ‘Sentential Metaphrastic’ into some semblance of order (its pages are neither numbered nor clearly arranged) ranks among the most pressing tasks for an archive still in search of a permanent home. Another is the prospect of issuing a series of fabled recordings made by Harry Smith of Lionel Ziprin’s grandfather, a rabbi in a kabbalistic lineage dating back as far as the 12th century. For two years in the early ’50s, Smith recorded ancient liturgical songs, chants and stories as channeled by the rabbi’s lone voice. A one-volume abridgement of a much-larger whole was issued publicly at the time by the record label Folkways but, for religious and family reasons, was snapped back into secrecy. The sounds have gone unheard ever since.

Plans for a release drawing on the complete set of at least a dozen private-press LPs, as well as more sounds on assorted reels of tape, remain in the works. As do desires to bring out reissues of the Inkweed greeting cards and assorted Qor Corporation materials, not to mention the publication of an array of related drawings, writings and correspondence that represents a culturally rich but still largely unexamined milieu. ‘My father was extremely protective of the things in his home,’ Zia Ziprin told me. ‘He would say: “You have no idea what’s here.”’

Steering the archive in whatever direction it will ultimately go has been Zia’s daunting duty since her father died in 2009 at the age of 84, and the project has been rife with complications. For one thing, Zia spent a significant part of her childhood estranged from him. At the age of seven, she moved with her mother Joanne and her siblings to California, to stay for a period in the house of Timothy Leary. It was Joanne who originally introduced Lionel to New York’s hip cultural scene, and she had been particularly close with Harry Smith, working with him on numerous projects and helping on animation for his later films. Her exit left Lionel in a state of crisis.

Zia didn’t see her father again until she was 18. After the family split, the tenor of Lionel’s religious devotion, always apparent if often unconventionally so, had intensified, making the prospect of sharing aspects of his prior life a fraught task. One of the problems holding up the recordings of his grandfather, for example, is finding a means for distribution that can be shut down entirely each week for Shabbos, the Jewish day of rest. Then there is the notion of releasing prized family materials, some dating back many generations, from the grasp of decades of close control. A scratch-paper sketch by Conner is one thing; a piece of decaying parchment with kabbalistic secrets from the 17th century is another.

For now, about half of the total collection is secure in Bove’s studio, by a stroke of luck after an instance of grave misfortune. In late 2011, an exhibition of the Ziprins’s greeting cards and assorted other materials went up at Glenn Horowitz Bookseller in New York under the name ‘From Inkweed to Haunted Ink: The Beat Greeting Card’. Then, in the midst of the show’s run, the curator, John McWhinnie, died in a freak snorkeling accident at the age of 43. Shortly after, with no notion of where the archival holdings might go, Philip Smith introduced Zia to Bove, whose interest in the era of Lionel’s youthful explorations had already been sparked. She also happened to have, in her spacious studio, a large safe in need of something to keep secure. It hadn’t been opened for ages and, owing to a vacuum seal from decades of disuse, its industrial metal door had to be opened with a car jack. Inside were old office decorations, cancelled cheques and ‘a machine gun, carefully hidden in a floral pillowcase’. Their replacements came by way of Lionel Ziprin’s even more mysterious holdings.

‘Part of what’s exciting about the archive for me,’ Bove said, ‘is that the Ziprins had this household that was a meeting point, a sort of salon or avant-garde nerve centre that has not been very well documented or even known about in art-historical records. Lionel Ziprin was somebody who people went to, to learn from. He was a stop on the agenda. That [the materials] exist and have certain qualities says something about how they were made, a particular type of social interaction and process.’

What kind of interaction, what kind of process? ‘Aside from the capitalist enterprises, like the laminates or the cards, most of the stuff seems detached from any kind of purpose, which is really refreshing,’ Bove says. ‘It’s not like everybody wasn’t a narcissist or didn’t have a huge ego, but the things they were making didn’t necessarily serve that. They seem detached from the lust of result.’

Philip Smith concurred. ‘There are certain types of figures that are more amenable to historiography,’ he said, ‘but these guys’ – Lionel Ziprin and Harry Smith and others in the milieu – ‘are really hard to pin down. In fact, when you pin them down you’re almost spoiling the sample. It’s like a quantum art history: if you’re observing them, you can’t figure out both their position and velocity at the same time.’

Harry Smith exemplifies the notion, as a polymath so prodigious that any attempts at classification quickly turn to farce. ‘What I find interesting about him,’ Bove said while peering down at a print of Smith’s Tree of Life in the Four Worlds (1954), ‘is how resistant he is to categorization or consumption on any level. You could try to consume part of it, but it will resist you. Sometimes with a work of art you can know and interpret it, and there’s no remainder. It’s consumable. But with his work, the more you look at it, it just becomes more and more detailed. You don’t arrive anywhere – you just keep going deeper in. There is way more that remains than what you’re actually able to reckon with.’

For Zia Ziprin, the idea is to find an accessible, sustainable home for the archive so that attempts at such reckoning – with Harry Smith and her father and so many more – can continue. ‘We need a space,’ she said. ‘We need a whole production company.’