Torkwase Dyson’s Collaborative Exchanges with Christina Sharpe

The artist and theorist share their thoughts on their intellectual work of interrogating legacies of slavery and anti-Black violence

The artist and theorist share their thoughts on their intellectual work of interrogating legacies of slavery and anti-Black violence

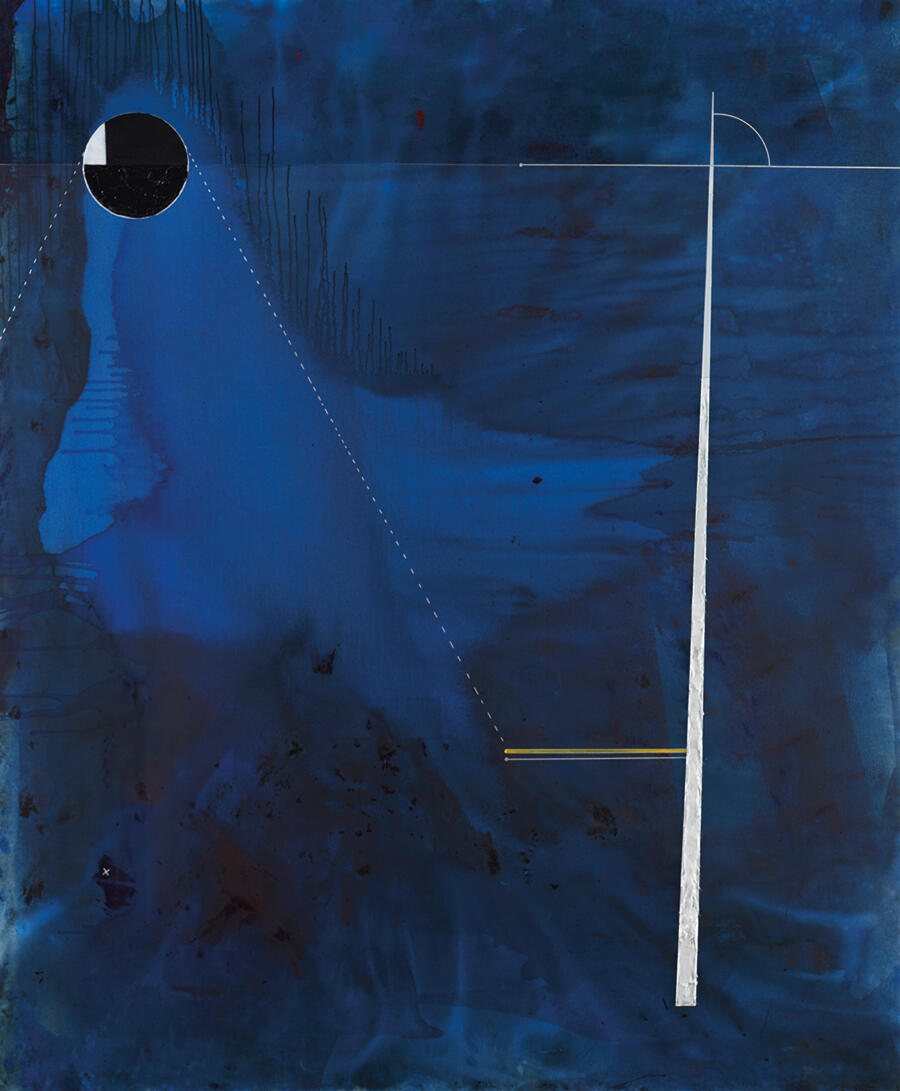

Christina Sharpe I last saw your work in November at ‘A Liquid Belonging’ – your most recent show for Pace Gallery in New York, where you exhibited a series of sculptures and canvases – but it’s been a while since we spoke at length about your practice.

Torkwase Dyson I remember how helpful you and the poet Dionne Brand were when I was figuring out the title for that show, how we talked through the language together. I wanted to hone in on something that I’ve added to my practice in terms of my methodological thinking: how distance influences questions of time and space and the becoming of Blackness in terms of the violent extraction and the brutal conditions of the transatlantic slave trade and the Middle Passage. I’ve been thinking about the oceans, the plantations, the enforced migration and how ideas of distance inform our languages, voices, movements and aesthetics. How do paintings and sculptures evidence the quotidian, the immediate, then form-shift to tell a tale? Likewise, in terms of composition, I’m interested in the relationship between perspective and belonging. What’s here in this space? What’s over there? What can I feel immediately and what feeling am I going to offer the audience by way of walking that distance?

CS That makes me think about the ways your sculptures take up space: despite their size and density, you can walk through and around them, and they offer all these potential hiding spots. I keep thinking of the beautiful colours they contain – flashes of yellow or bright blue – which you might not notice within their predominant blackness if you weren’t really looking. It was strange seeing your works in a traditional white-cube setting in New York because I really wanted to experience them the way we did in 2021 at ‘Liquid A Place’ – your show for Pace Gallery in London – when we stood on them, rocked them, swung from them, sat in them and touched them. It’s another instance of the different relationships between here and there, and of how we relate to objects that speak to both the past and the present. It reminds me of something the writer Saidiya Hartman said at the launch of her book Wayward Lives: Beautiful Experiments [2019]: ‘Time isn’t horizontal; it’s vertical.’ It also makes me think about how soil collection works: you dig down and you bring up all these layers. Time, experience, affect, theorizing and movement are likewise layers in your work and your thinking about Black life.

TD The three sculptures from ‘Liquid A Place’ will be included in this year’s Liverpool Biennial. They’re precariously weighted: what starts out as liquid becomes solid and, eventually, begins to crack. The materiality of the sculptures also relates to this idea of time, application, the body and the mark; the bottom half of the sculpture comprises black rolled steel in a reference to industry. As you put it so eloquently in your work In the Wake: On Blackness and Being [2016], Black people are still living in the wake of that industry, in the wake of those oceans, in the wake of all those conditions of anti-Black violence. We’re still in the wake of this thick air of what it means not only to survive such dispossession but to move on to autonomy without the granting of emancipation. From working with you, I have learned how to think about the atmosphere in which we exist. And, from reading your book, I have understood on a visceral level your thinking in terms of the experience of the Middle Passage – what it means to actually be in the wake of a ship, to have that water in your body and on your body and over your body – and, consequently, what it means to be Black in America. That being, belonging, becoming: I still tap into it when I’m working. When I’m drawing, sometimes, I find myself working towards your work.

You’re a scholar, a writer and a poet. The way you deal with language feels like a pointed and informed search rooted in a deep, ongoing criticality. I say it with my soul: observation is so powerful when thinking about what ‘ordinary’ means in relation to these moments of noticing – whether that’s noticing a catastrophe or an instance of care. You have transformed how powerful the ordinary can be as an experience.

CS I am a deep admirer of your work – of the ways that you think and then make objects in the world that both clarify and extend that thinking. You’ve said a number of things that I think about all the time, that have informed and continue to inform my work. The most recent one is from your essay ‘Black Compositional Thought, Black Hauntology, Plantationocene and Paradoxical Form’ in photographer Dawoud Bey’s catalogue Two American Projects [2020]: ‘Blackness will swallow the whole of terror to be free.’ I’m going to keep thinking about that. You said that Bey has made a dark space a Black space. Swallowing terror allows us to move because, otherwise, what would we be in the face of terror? It rewired my brain, thinking about that sentence – about what it means in terms of what we are faced with now, what we have faced for the past 500 years, and what we will face in whatever kinds of futures we must insist on making. It means something not to be lost in the face of terror but to move through it. Because how else did we move? Terror every step of the way – from the capture to the marching, to the barracoon, to the littoral, to the ship, to those few inches of space on the ship, to the arrival, and on and on. What spaces have we been in since the 15th century where we have not faced that kind of terror? Your work offers us a way to think about what we might learn from that about how to survive and imagine something else.

TD We’ve collaborated on paintings, drawings, sculpture and film. Part of my practice is to understand the potential for state change in catastrophe and refusal, and the ways in which this condition of change happens within the architecture and infrastructure of America. The fact of the Black body being extracted into a material thing – and only a material thing – was used to convince us that there was no possibility for change. It’s antithetical to being in itself. I have a deep fidelity to understanding when, and in which context, that state change happens and to pointing towards potentially liberatory moments within it.

CS In my own words – in In the Wake – I wrote that we, as Black people, have been made through overwhelming force, but we are not only known to ourselves and to each other by that force.

TD The ethos of In the Wake is indelibly planted in my mind. As an artist who puts things on display, it’s not uncommon to be mistaken for someone concerned solely with the conditions of display. However, it’s really important to me that my work functions not only as a witness for multiple audiences but as a condition of belonging outside of these larger contexts of display. Anyone can look at my work, but who I’m talking to, who I’m addressing, who I’m in conversation with …

CS They are two different things, right? Anyone can approach, but whether you are included is a different matter. You can overhear a conversation, but you’re still just overhearing it.

TD I like the fidelity of that kind of exchange – with you, Dionne, all of the people I’m in conversation with. I find that very much in the Black radical tradition.

CS I keep thinking about the academic and theorist Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s book Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History [1995], in which he writes: ‘The past – or, more accurately, pastness – is a position. Thus, in no way can we identify the past as past.’ Our position in relation to these ongoing violences is precisely that: the past is not past; it is being transformed, but it is still the afterlife – the wake – of slavery.

Your fidelity to state change and my fidelity to finding a form that will let me say what I’m trying to say has something to do with my latest book, Ordinary Notes [2023], because I thought of the note in all of its meanings: as a memory, as a brief recitation of facts, as something that’s musical, even as the tasting notes in wine or coffee. I wanted to hold these and try to think through how they structure Black life. The book comprises a set of 248 notes about the ways in which I – we – experience the world around us: the things we remember, taste, feel, reject, embrace, understand, refuse, imagine, love. It also continues some of my thinking from In the Wake.

The title comes from Toni Morrison’s Beloved [1987], in which one of the novel’s protagonists, Paul D, ends up in prison for 86 days. While he’s there, he has time to make ordinary notes, to do the kind of thinking you’re talking about – recognizing each other, seeing each other, coming to trust and hold each other – which ultimately enables him to escape the chain gang. I wanted to consider those ordinary-extraordinary aspects of Black life and what we can do, linguistically and aesthetically, with the ordinary.

One section of Ordinary Notes is titled ‘Lucida’ – a reference to Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida [1980] – in which I examine images of my mother and grandmother, asking: what would a camera lucida of the Black maternal look like? Every part of the book is in conversation with other people’s thinking, painting, drawing, singing. I see it as a way of bringing together people whose work I admire and talk about – to think about those words that animate Black life in order to better articulate what we call breathing, what we call tender, what we call life.

TD What I find so powerful about your work is its generosity: how you offer accounts and observations of other people’s artwork or ideas, how you break down definitions to create an ecosystem. You’re not only talking about witnessing something tender; there’s also something deeply tender about the way you read your own work.

CS I’ve been struck over the course of many years of reading and of watching movies and television programmes at how little tenderness is afforded to Black people – even as we may experience a different reality. In her latest book of poems, Tender [2023], the Black Nova Scotian poet Sylvia Hamilton talks about how the boat that took enslaved people from the main ship onto land was also called a tender.

I wanted the form to produce something. I think that the form of the note, through juxtaposition and accumulation, produces knowledge and feeling, creates its own momentum. I wanted that kind of momentum to carry readers through the book and to position them in various scenes – whether that was in relation to the museum, to white supremacists or to a series of photographs, texts or terms. I wanted that work of accumulation and juxtaposition to do the work of argument and, hopefully, of understanding.

TD I remember you reading from Ordinary Notes in ‘I Can Drink the Distance’, my two-part installation and durational performance at Pace Gallery in 2019.

CS I don’t remember if it was called Ordinary Notes at that stage; some of the notes that I think of as encounters were then part of ‘Black. Still. Life.’ Later, before an event at The Underground Museum in Los Angeles with Saidiya, she asked me what I was working on. I showed her the photographs of my mother and I mentioned that there was this other project I wanted to work on. She told me to do the other thing, the harder thing. I did and that eventually became Ordinary Notes.

TD That structure of forms is in the work: there’s a literary component, as well as a more documentary, archival component. Then, sometimes, this novel self shows up, and then this witness self shows up. How you position the witnessing with the language and the theories is transformative – and it has transformed me. I think this conversation – and the years of conversations we have had – really fossilizes the ways in which your work has been indelibly imprinted on my hands: it’s this idea of accumulation, of dispersal, of witnessing and of the spaciousness of Black being very tender to the system. When I look at your work or hold your books in my hands, I feel that spaciousness abounds. I’m so glad you’re my friend.

CS I’m so glad you’re my friend. As you were talking, I was thinking: wow, to have someone speak your work back to you is such a gift; but to have someone with your brain, heart, insight and attention do it is beyond a gift. While we were talking, I wrote down what you were saying and I attempted a little drawing. I am so grateful for the ways that you have rewired my brain.

Audio recording by Dossiers HQ. To hear more stories, subscribe on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

Torkwase Dyson’s ‘Bird and Lava’ is on view at the James M. Kemper Gallery and Video Gallery, St. Louis, until 10 July

This article appeared in frieze issue 236 with the headline ‘Conversation: Torkwase Dyson and Christina Sharpe’

Main image: Torkwase Dyson, Liquid A Place, 2023, installation view. Courtesy: © Torkwase Dyson, Desert X and Pace Gallery; photograph: Lance Gerber