No Resolution

Included in the German pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale, Hito Steyerl’s pointed and playful disruptions in digital environments

Included in the German pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale, Hito Steyerl’s pointed and playful disruptions in digital environments

Motion capture is a trick often used by filmmakers to achieve the most realistic rendering of animated figures. It is based on the transfer of recorded information: a human body is wired to send a constant flow of movement data, creating what might be called a ‘skin’ for a virtual body, corresponding to the movements of the ‘recorded’ body. In a society increasingly structured by data technologies, the symbolic relevance of this procedure is obvious. And so it makes immediate sense when Hito Steyerl answers a question about her work for the German pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale by saying that motion capture will play an important part in it. And that in a Skype chat, she also sent me a text on the subject, a four-line manifesto: ‘Our machines are made of pure sunlight. Electromagnetic frequencies. Light pumping through fibreglass cables. The sun is our factory.’ This smacks of technological utopia and riffs on Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto (1991), subtitled Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. In the form of an ‘ironic dream’, Haraway’s ‘political myth’ proposed ‘a common language for women in the integrated circuit.’ Today, Haraway’s enthusiasm cannot go unqualified, as the emancipatory potential of digital technologies has given way to the new alienation of subjectivity exploited in the service of precision-targeted consumer incentives.

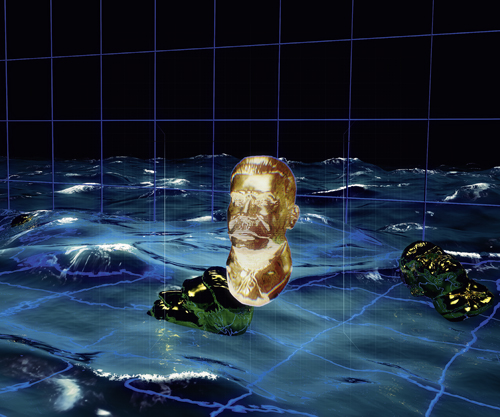

Steyerl admits that the phase of ‘euphoria and playing around’ with digital channels is perhaps over, but she does not wish to completely subscribe to this view. Her work for Venice, in essence a single-channel video installation, will recall a not entirely serious computer game. And it will search for a way of visualizing the ‘grid’ into which all the information currently being collected about users can be entered. This puts Steyerl’s Biennale piece firmly in line with her work of the past five years, in which her playful treatment of user interfaces includes the persona that she embodies in them: a stewardess pointing the way to a parachute as the alternative to a mighty crash (In Free Fall, 2010); a scroll-and-swipe demiurge wearing a black outfit recalling martial arts (How Not To Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, 2013); a tourist taking pictures with her mobile phone on Pariser Platz in Berlin, with reverse shots showing a war zone in the Middle East (Abstract, 2012).

Steyerl has often suggested that she is sympathetic to the idea of disappearing, that she sees ‘going off screen’ as a plausible solution, but that by doing so one forgoes the many alternatives to vanishing without a trace listed in How Not To Be Seen: ‘being invisible in plain sight’; becoming invisible by becoming a picture; becoming invisible by living in a gated community; becoming invisible by being a woman over 50.

The last ‘option’, delivered in a tone of casual sarcasm, is of course not an option at all, pointing instead to the backlash against which Haraway’s cyborg vision was directed: conservative re-naturalizations of gender relations that are not especially easy to deconstruct in the swipe-away apps now often used to organize interpersonal relationships.

In the Massimiliano Gioni-curated The Encyclopedic Palace at the Venice Biennale in 2013, How Not To Be Seen was installed right at the back, in the Giardino delle Vergini, in a building whose dilapidation and seclusion stood in stark and presumably deliberate contrast to the ideal, data-synthesized worlds shown in the video. As her point of departure, Steyerl took a graphic object, a ‘resolution target’ used to calibrate satellite observation. This is easy to imagine if one has ever used Google Earth to zoom in from space to the Earth’s surface. Eventually, a point is reached where no higher resolution is available. The ‘resolution target’ corresponds to one pixel in a satellite picture. In 1996, the target’s sides were 12 metres long (in the Californian desert she found an actual example, around which the film unfolds). Today, one pixel in the global view has sides just 30 centimetres long. That corresponds roughly to the size of a shopping bag, or the paper boxes inside which characters in How Not To Be Seen stick their heads.

In a metaphorical sense, the ‘resolution target’ is also the individual human, not just those who may harbour terrorist intent, but anyone who tries to escape visibility in any way. For a few minutes, figures dance around dressed in burqas, or in green overalls that seem perfectly suited to disappearing in front of a green screen. And it is not only human beings who might develop an interest in not being recorded: the data themselves start to baulk. ‘Happy pixels hop off into low resolution’ after an iPhone emits explosive signals.

With her sometimes parodic strategies, Steyerl has more in common with the subversive filmmaking of Craig Baldwin than with Harun Farocki, with whom she is often linked, so much so that she has plans to co-found a Harun Farocki Institute in his memory. Baldwin stands for a practice of détournement and anarchic counter-semantics (he is best known for his 1991 film Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America that illustrates reactionary and interventionist US foreign policy during the Cold War using excerpts from sci-fi B-movies), and for strictly analogue image production. Steyerl shares this interest in appropriating pop-cultural materials: in How Not To Be Seen, the Three Degrees appear singing their 1973 hit When Will I See You Again. The three singers are integrated into virtual reality (that constitutes something like an artificial paradise inside the powers of surveillance) and digitally anonymized.

Freed from space-time order, signs travel all the more quickly. But Steyerl is not interested in transferring the familiar mimetic order (content/form) into an open-ended logic of all-embracing digitality in which not only the ‘resolution target’ but also critical discourse vanishes. On the contrary, playfulness and role play are a form of rationality within a context which Steyerl, who is Professor of New Media at Berlin’s University of the Arts, has coined ‘circulationism’. As a result of the ‘liquefaction’ of critical visual practice – addressed in works like Liquidity Inc. (2014) or In Free Fall – her films, often shown as part of installations, do not appear particularly installed even when presented as single-channel screenings. This has to do with the desktop look she often gives them: even where she uses a single moving image, it contains a multiplicity of user windows, images being clicked in and out of view, and the kind of pop-up inserts that have now turned every desktop and mobile phone into a de facto installation. In Liquidity Inc., a masked man presents a weather forecast for global capital against a backdrop of Tumblr-like images – capital itself as both image and substance of circulationist liquefaction.

In these new works, Steyerl inevitably risks limiting herself to mere heightened mimicry of ‘produsage’. This risk is balanced by other works with more nuanced formats: Abstract is a constellation of images communicating along the visual axis of shot/reverse-shot that could almost be read as an homage to Farocki. As in Farocki’s work, the ‘reverse shot’ here is often not a second image but an insert, something to read, a conceptual response to an image. ‘The grammar of cinema follows the grammar of battle’, reads one such statement that is both apodictic and aphoristic. The smartphone itself contains an abstraction of the shot/reverse-shot model insofar as it is both camera and cinema at the same time, capable of filming and screening an endless succession of films.

The decisive ‘reverse-shot’ in this short piece, however, involves a reference to Steyerl’s artistic biography, as it includes another commemoration, this time of the German activist Andrea Wolf who was killed in the Kurdish region of Turkey in 1998. Wolf was a personal friend of Steyerl’s and ‘starred’ in her films November (2004) and Lovely Andrea (2007). In this case, rather than any picture of Wolf, a man recounts a detail of the circumstances surrounding her death (when she was already dead, her breasts were cut off) – a detail that evokes the cruelty that has become an almost routine feature of recent IS propaganda videos. There is no picture of this in the film, as Steyerl explicitly leaves words to make the graphic impact. In her films, she switches between documentary strategies linking visual worlds to specific everyday observations usually based on linguistic utterances, and the explosive mixing of all forms where language becomes a frenzy of buzzwords and images can never gain a foothold.

The best of her recent works have been documentaries. Adorno’s Grey (2012) is devoted to a research project that may seem absurd at first glance: in the Frankfurt lecture hall where Adorno gave his last lecture in 1969 (and where he was confronted by the bare breasts of protesting female students), she tried to uncover the grey colour with which Adorno allegedly had the walls painted because he said it would enhance concentration. The wonderfully guileless question ‘Might there still be something under there?’ could be used as a heading for Steyerl’s entire oeuvre, as it amusingly leads ontological archaeologies of the kind that were briefly used as the base for resistance against digital arbitrariness into the void of a hole in the wall. Underneath, according to Adorno, there is always the concept, though it is never identical with itself. In Adorno’s Grey, this layering of over and under also acquires an art-historical association: grey, the neutral sister of the absorbent Malevich black, re-liberates discourses that had been taken to every possible zero point by classical modernism.

In her film Guards (2012), individual idioms (in this case that of two African-American museum guards in Chicago) are the actual picture support. Although only required to maintain order and quiet, one of the men misunderstands his job as follows: ‘I run my walls’. He patrols the museum in the style of a soldier in Vietnam or Iraq. There could always be a threat round the next corner, but it’s always just an artwork. Once again here Steyerl plays with the simplicity of swapping backgrounds in digital image production and arrives at a punchline: fine art is also such a ‘grid’ onto which she transfers the footage from her engagement with these two guards. War, the police and security are the contexts shaping the men’s suspicious gait, not any reverence for the auratic artwork. In the final credits of Guards, where the director’s name should be, we read: ‘Security by Hito Steyerl’. This is rather a drastic claim, but it is backed up by Steyerl’s work. Anyone active in image production today, anyone facing the conditions of digital power relations, must be on guard: the threat to the soft target of art comes via the constrictive tendencies of circulationism.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell