A Vindication of Conceptualism

Robert Storr compares Lawrence Weiner and Kara Walker’s projects of the early 2000s

Robert Storr compares Lawrence Weiner and Kara Walker’s projects of the early 2000s

Let’s just call it misconceptualism. You know it when you see it, and you see it everywhere in art exhibitions, at art fairs and – first alert! – in art academies, where it incubates like a low-grade infection in the hidden recesses of seminar rooms, nourishing itself on inarticulate obscurities fostered by the ‘strong’ misreading and/or helpless misunderstanding of critical discourse. It is idea art without an idea, identity art without an identity, the ‘Oh wow!’ school of 1960s’ philosophy and politics updated for the 2000s, the spawn of bone-headedness and the bon mot. Misconceptualism is the zone where narrow minds go to escape self-induced claustrophobia only to find the abyss. It is a ‘counterculture’ of deeply insecure, often resentful, all too often petulant scholastics, and, as a result of an ever-growing labour force of underemployed or ‘lumpen’ theorists, its apologists and enablers outnumber its practitioners.

But this column will not be devoted to a general complaint. Rather, my purpose in making it at the outset is to set the stage for celebrating in inverse proportion two artists who vindicate Conceptualism and its offshoots at a time when that tradition is widely travestied or trivialized by wannabes: two artists whose work shows how far the ramifications of having a substantial but protean idea and a hard-won but mutable identity can go, as well as how far work thus grounded can take a thoughtful and observant public.

As it happened, their retrospectives were simultaneously on view at the Whitney Museum last winter, neatly drawing the comparison for elevator-riding museum-goers who made their way up or down the building floor by floor. (Who says the psycho-geographic equivalence between our cultural institutions and department stores is all bad?) Of the two, Lawrence Weiner was the old master. And of the two his exhibition rates as one of the most beautiful New York has seen in recent years, owing to its combined openness, spareness and fullness. For Weiner, text is image in a double sense; his elliptical phrasings and shifting punctuation gently nudge propositional prose towards matter-of-fact poetry even as exquisitely plain but visually arresting typography converts word into graphic pictures that concretize thought while transcending logic. Example: ‘LAID OUT FLAT/BENT [NOW] THIS WAY/TURNED [NOW] THAT WAY/in effect LOOPED OVER.’ This is language as relational sculpture. Example: ‘MANY COLORED OBJECTS PLACED SIDE BY SIDE TO FORM A ROW OF MANY COLORED OBJECTS.’ This is language as still life, with the subtle ambiguity of whether ‘many’ modifies ‘colored’ or ‘objects’ triggering multiple variants in the mind’s eye. Weiner, of course, was a founding father of Conceptual art, and these slippages are characteristic of its cryptic phases – one finds them in Bruce Nauman too – but nowhere outside Weiner’s work does one experience the emancipation of sound, sense and sight more fully. To look back on his career is thus to reread the fragments that set language free – free to notice, to wonder, to marvel at its own plasticity and polyvalence.

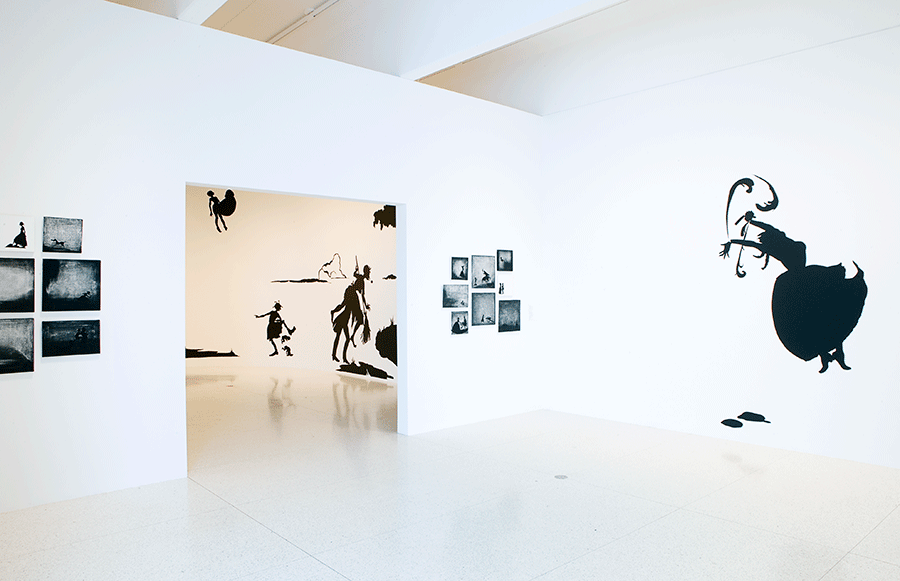

The younger half of the Whitney pair was Kara Walker. She too has sought to liberate signs and symbols from bondage, but in her case, as has been typical of her historically sceptical Postmodern generation, linguistic play involves etymological back-checking and cross-referencing as much as it does semantic inversion and formal reversal. While text is image for Weiner, for Walker images are texts – texts waiting to be reconfigured and rewritten or commented on by other texts. Of course, the chains that bind them to their original meanings are the unspoken attitudes that readers bring to Walker’s narratives, attitudes she explodes in the face of the viewer/reader like the firecracker cigar that explodes in the minstrel show comic’s cork-carboned visage. In this sardonic vein Walker’s silhouetted tableaux are burlesque pantomimes of American racism that mock those who mock the ‘Other’. Meanwhile her verbal vignettes seethe with bitter ironies that destabilize conventional thinking just as thoroughly as, but far more jarringly than, Weiner’s laconic koans. Like him, she conjugates colours and objects but with ‘a difference’. Unlike him, she conjures with colouredness and objectification. Example: ‘MANY BLACK WOMEN ARE PHYSICALLY STRONG/MANY BLACK WOMEN HAVE ACTIVE, HEALTHY SEX DRIVES/MANY BLACK WOMEN ARE THE SOLE PROVIDERS IN THEIR FAMILIES/MANY BLACK WOMEN FACE DISCRIMINATION IN THE WORKPLACE.’ Thus Walker blackens the white page of literary Modernism and marbles its white cube.

At the close of a long, contentious season one looks back with heightened appreciation at moments of intellectual and artistic clarity. In a period when the ‘interrogation of the subject’ so often descends into essentialism and solipsism one is grateful when questions addressed to the viewer acknowledge that both the viewer and the questioner are possessed of a complex consciousness. And in a context where ‘misconceptualism’ grabs headlines, causing the talkers to talk ad nauseam, one seeks dialogue that lends existential substance to weightless ideas. On all counts Weiner’s and Walker’s exhibitions were highlights of a murky year.

Main image: Kara Walker, ‘Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love’, 2007, installation view. Courtesy: © the artist and Walker Art Center; photograph: Gene Pittman