WACK!

Peggy Phelan defines Feminism as ‘the conviction that gender has been, and continues to be, a fundamental category for the organization of culture. Moreover, the pattern of that organization favours men over women.’ Described in this way, Feminism is a nebulous and inclusive category:

a constellation of social and political movements, states of mind and modes of practice united by a ‘conviction’ and a picture of how the world operates. ‘WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution’ aims to use Phelan’s comprehensive definition to revise the story of feminist art in productive ways – not least by bringing into view artists and art works excluded from feminist art’s historical manifestation.

The exhibition’s remit is the period from 1965 to 1980 – roughly the moment of so-called ‘second-wave’ Feminism – which allows the show to include artists of different generations (Louise Bourgeois to Theresa Hak Kyung Cha) and of 21 nationalities. Alongside scores of well-known female artists, whose place in the history of art is secure, were dozens whose work merits further investigation, including Americans Howardena Pindell and Senga Nengudi, Chileans Cecilia Vicuña and Catalina Parra, and Croatian Sanja Ivekovic.

Ivekovic’s photomontage series ‘Double Life’ (1975) was a distinct revelation. Something like Richard Prince avant la lettre, Ivekovic matched the postures struck by models in magazine illustrations to earlier photographs of herself posing and staring into a mirror – as if discovering in her personal history some secret code that magazines such as Marie Claire and Elle had discovered later and put to use to sell underwear. The ‘fictions’ built up in advertisements are not mere enticements, the artist claims, not just alien fantasy worlds we dream of living. They’re ours in some basic and unnerving way.

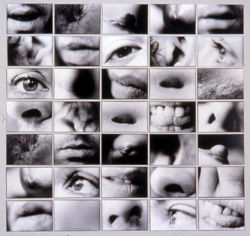

Curating exhibitions in the Geffen Contemporary seems like a thankless task. Almost any major show looks jumbled and confused in its hangar-like envelope. By organizing according to thematic clusters, curator Connie Butler did better than most with a bad situation. One section, which tested abstraction’s claims to universality against the female bodies that produced it, made good sense; another cluster, devoted to the body as medium (including forceful works by Gina Pane, Marina Abramovic and Carolee Schneemann), worked fine too. One has to wonder, though, if a theme (‘Speaking in Public’) that manages to unite Faith Ringgold’s declarative poster Woman Freedom Now (1971) with Cosey Fanni Tutti’s frank clippings from her career in the porn industry (Prostitution, 1975) isn’t doing some violence to the meaning of the works – and to the dignity of Ringgold’s activism in particular. ‘Social Sculpture’ presented a similarly elusive grouping, putting forward under Joseph Beuys’ clunky phrase Bonnie Sherk’s The Farm (1974–9), Suzanne Lacy’s bleak investigation of prostitution (Body Contract, 1974) and Lygia Clark’s quirky, psycho-perceptual devices (Arquitectura Biológicas, 1968).

According to Butler, these themes ‘make the case for women whose practice may have fallen outside the articulated language of feminist art’, especially those in isolated circumstances. Even so, it was hard to see how Clark, whose work acknowledged no distinction between genders, made sense in this exhibition. Her favoured term was ‘human’. Similarly it seemed perverse to include artists such as Jay DeFeo, who scorned Feminism, or the obnoxious Orlan, while leaving out most of the artists who attended the Feminist Art Program at Fresno State and CalArts.

The exhibition suffers most by abstracting feminist art from the political movements that gave it force and meaning. One might be forgiven for being mystified by the fact that feminist artists took labour struggles to be a central issue (for example, Berwick Street Film Collective, Nightcleaners, 1970–5). The unequal division of labour is not mentioned anywhere conspicuous. Despite language, autobiography and confessional being everywhere in the exhibition, the ‘consciousness-raising’ discussions where such personal testimony gained political meaning are obviated. Without it these fundamentally political techniques look merely modish.

Several questions are left hanging. What accounts for the lag between radical Feminism’s emergence as a political movement (gathering momentum through women’s experiences on the front lines of the civil rights and student movements throughout the 1960s) and feminist art (articulated as such in the early 1970s)? How were these ideas transmitted to Chile, Croatia, Australia and elsewhere – how did it become an international movement? And what brought this investigation to a close in 1980? These questions are answerable; not addressing them in the exhibition makes the titular ‘Feminist revolution’ an empty signifier or, worse, a myth, locked in some distant, inaccessible past.