Watching the Mind

On the occasion of ‘I ♥ John Giorno’ in Paris, an interview with John Giorno about poetry, art and radicalism

On the occasion of ‘I ♥ John Giorno’ in Paris, an interview with John Giorno about poetry, art and radicalism

If he weren't such a non-conformist, poet, performer, artist and activist John Giorno could be compared to Woody Allen's Leonard Zelig — a presence at every flashpoint in the arts from the 1960s to the present. There he is as the subject of Andy Warhol's film Sleep (1963); in Tangier with William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin as they refine the cut-up method; in mid-1960s New York with artist Robert Moog, designing multimedia 'happenings'. There he is in the mid-1970s at CBGBs with Patti Smith, Jim Carroll and other proto-punks who took inspiration from his performative approach to poetry; and, in the 1980s, making records on the Bowery with Burroughs, Lauris Anderson, Lydia Lunch and other downtown luminaries. Decades later, he reappears in the video for R.E.M.'s final single, 'We All Go Back to Where We Belong' (2011). And on and on. Giorno's partner, artist Ugo Rondinone recently documented this long journey of mutual influence and conceptual promiscuity at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris. A meticulously curated exhibition of a massive, well-tended archive, Rondinone's 'I ♥ John Giorno' is not only a love letter to the poet but a Wunderkammer of artistic experimentation.

I spoke with Giorno in his loft on New York’s Bowery, where he occupies three floors, including the legendary apartment known as the Bunker, where Burroughs lived. I felt like I was at the centre of a vast, intricate web of connections, a charmed nexus of art and activism, decadence and spirituality, performance and meditation, sexuality and celebrity. At its epicentre was a compact man with white hair and a ready laugh; a living repository of postwar us art and radicalism, and one of the nicest people you’d ever meet.

Andrew Hultkrans Tell me about the genesis of the show at the Palais de Tokyo.

John Giorno Ugo and I have been partners for 18 years. He knows everything about my life. My parents lived in Roslyn Heights, Long Island, and for decades I filled up cars with my work and drove it out there to store it in the attic. Fifty years later, Ugo saw the archive on Long Island and it percolated in his mind.

AH Did Ugo collaborate with you?

JG Not at all. It was a work of art by Ugo, and I helped and let it happen. I was just the paint and the pigment. Going back 50 years with Warhol, on his films such as Sleep, I wouldn’t offer suggestions because I’m not a filmmaker. I knew enough to keep my mouth shut. Ugo methodically created this miraculous display in the galleries. His designers in New York calculated every inch of the thousands of things in the show. Ugo made the decisions, having seen many archives in installations around the world that never worked. They’re usually fetish collections of things you can barely see. So, he had my archive scanned – 11,500 scans of everything I have in print – and had them all in duplicate affixed to the walls and the scans in books on tables: a book for each year from 1936 to 2012.

AH When you saw the finished product, did you think: ‘This is me’?

JG A beautiful distortion of my distorted mind. [laughs]

AH What were you up to when you met Warhol in New York in the early 1960s?

'I saw how the different pop artists were working and I said to myself: Why don't poets do that?'

JG I went to Columbia from 1954 to 1958 and, afterwards, my parents continued my allowance to support me as a poet. Then, after a few years, I got too crazy. My father said: ‘John, you should get a job.’ So, I worked on Wall Street. In those years, Wall Street was not like a Hollywood version of hedge-fund guys: it was a gentlemen’s club; so, I did that for a year and a half. But, before that, I had friends downtown. I knew Allan Kaprow in 1958 and ’59. I met Wynn Chamberlain in 1961. He had just moved into the building where we are now at 222 Bowery. In 1963, Chamberlain threw me a birthday party on the top floor. There were about 80 guests, and it was everyone in the art world. The seven pop artists, Rauschenberg – who came early with Steve Paxton and left before Jasper Johns arrived, because they had broken up – Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Frank O’Hara as well as dancers and musicians, Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown, Steve Reich; every artist you could imagine. They came because they wanted to be together. It had nothing to do with me. It was because it was so early. Four years later, they would never have been together at the same party because they became so famous. I entered that small art world when people actually liked each other.

AH There’s a story about you and Warhol going to an O’Hara reading. The venue was packed. There was no microphone or amplification, and Warhol turned to you and said: ‘It’s so boring. Why is it so boring?’ And that switched a lightbulb on in your head.

JG That was a seminal moment. I was going to artists’ lofts, galleries, openings and parties every day in those years, and I saw how the different pop artists were working, and how they allowed new ideas to arise. So, I said to myself: Why don’t poets do that?

AH And you were famously also not in love with New York School poetry.

JG It was more complicated. I was sort of a member of the second generation of the New York School in the very early 1960s. I had first read O’Hara in 1957. It wasn’t as important to me as Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ [1955], but I saw poetry in a new way after reading his work. They were all so mean, though. [laughs] O’Hara hated Warhol, and he didn’t like Burroughs either. He was old-fashioned and believed painters should paint abstract paintings. Warhol silkscreened, so he was a commercial artist, and Burroughs worked with cut-ups. It was about O’Hara not liking dada, not getting it, and refusing to admit he’d made a mistake …

AH You also had a problem with the way that the gay poets in the New York School would allude to their sexuality in their poetry. Your ‘Pornographic Poem’ [1964] seemed to be a response to the way they were dancing around the issue in their work.

JG In 1964, there were all these gay artists, but they didn’t allow gay images in their work, nor was their gayness reflected in their work because it would have been the kiss of death. You couldn’t be a gay artist at that time. The abstract painters’ art world was homophobic, as we know. Ginsberg’s use of gay images in a very direct, ordinary way in ‘Howl’ and Burroughs’s use of gay images in Naked Lunch [1959] empowered me as a poet.

'With Burroughs, it was like getting hit with a baseball bat. Drinking and taking a lot of drugs daily with him for nine months, I got truly radicalized.'

I wrote my first found poem in March 1962 – before I met Warhol the following November. At that time, everybody used the found image, and the influence was from these artists – Rauschenberg, Johns, Warhol, Jim Rosenquist. Even though I had learned about dada and Marcel Duchamp in college and understood the concepts, that wasn’t the influence for me; it was seeing them do it. I continued using found images in my work for 15 years.

AH You were with Burroughs and Gysin when they were further developing the cut-up method. Were you contributing to their experiments?

JG I was quite close friends with both. It was 1965 and I was really a kid, in awe of these guys. They were both around 20 years older than me. I was doing found poems and starting to work on sound compositions with Gysin, and they liked my work. It transformed my life. Burroughs politically radicalized me. In the 1950s, I had supported civil rights, but in the art world there was no political involvement in 1965. With Burroughs, it was like getting hit with a baseball bat. Seeing him on a daily basis and drinking and taking a lot of drugs daily with him for nine months, I got truly radicalized, which set me off on another path. But I never used the cut-up method in my work. One of the principles with found images is that you don’t touch or transform them.

AH Can you tell me about the ‘happenings’ you staged later in the 1960s?

JG I was introduced to the idea of using technology by Burroughs and Gysin in 1965. There was something called poésie sonore – sound poetry – in France. It was a movement that Gysin was part of and Burroughs also used sound in his work. I did a sound collaboration with Gysin in 1965, which was presented later that year at a biennale at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris. And then, in 1966, I worked with Rauschenberg in e.a.t., Experiments In Art and Technology, and I met Bob Moog through Rauschenberg. I was already working with sound, so I asked Moog if we could do something together. In the early 1960s, I knew Steve Reich and Max Neuhaus. They had these spliced tape-loop pieces. I said to myself: if they can do loops for this dumb music, why can’t I do it for my words? So, I developed a system of making sound compositions. The idea was to take a room the size of an average gallery or performance space and fill it using different elements of sound and light, sight and smell, and whatever else: the five senses.

AH How did people respond to these poetry happenings?

JG My fans loved it. But I was between three worlds: the poetry world, the music world and the art world, and not appreciated by any of them, so I stopped doing it. I did it from 1965 to 1970, and then went on to focus on writing and performance.

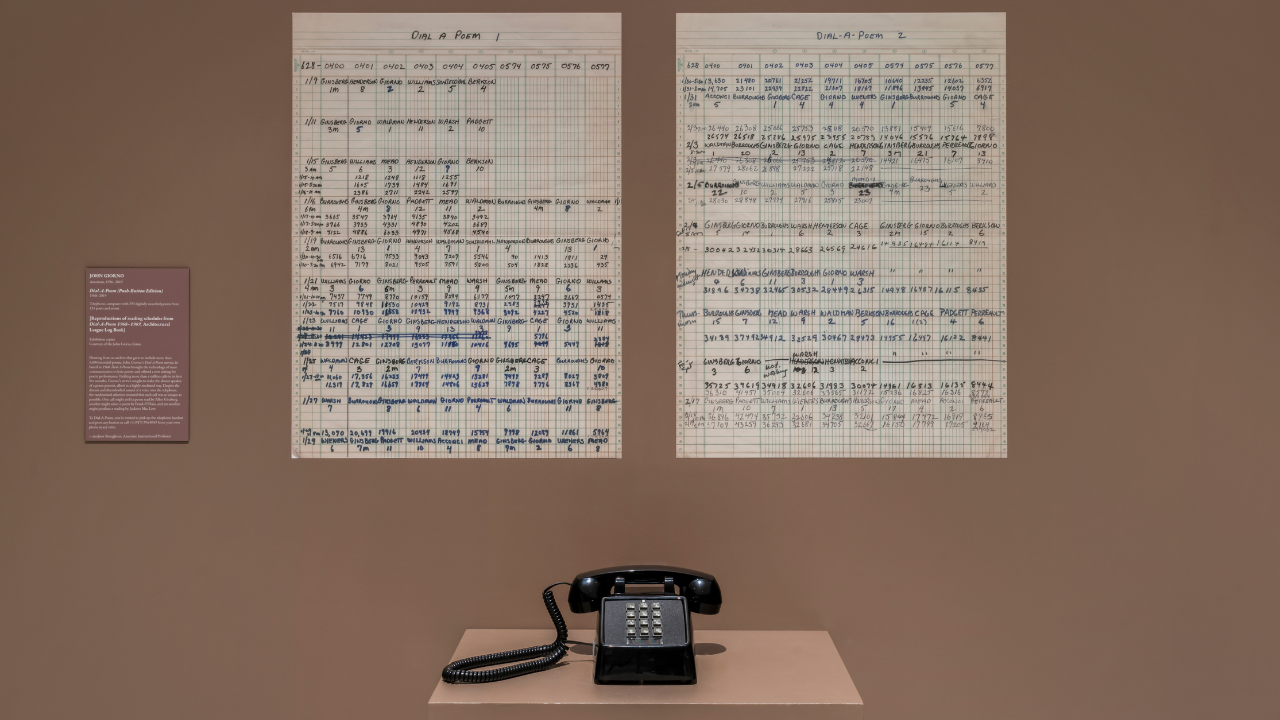

AH In 1968, you developed the ‘Dial-a-Poem’ project.

JG The first poets were my friends: Burroughs, Ginsberg and Cage – who sat over there [points across room] and read from Silence [1961] – and Diane Di Prima. There are magical moments in your life where everything gets transformed because, even though you don’t know what you’re doing, somehow it’s hugely successful. The project was sponsored by the Architectural League, who put out a press release, and then there was an article in the New York Times where they printed the telephone number. Thousands of people called; soon, it was millions. The idea that you could connect content with a phone number and advertise the number ended up creating a new dial-a-something industry.

AH How did you initially come to practice the Nyingma lineage of Tibetan Buddhism?

'Meditation is good for all artists, but particularly for poets and writers. You build a muscle where you're able to see throughts arising and grab them.'

JG I was introduced to Buddhism at Columbia College, but the only place for meditation I knew in New York was the Zen Center on Park Avenue, and my instinct was not to go there, as that’s where I was running away from. So, skip to 1965 and I’m taking LSD with Gysin in the Hotel Chelsea. When you have a good trip, you have a good trip. But I realized that when you have a bad trip, it’s not the drug; it’s your mind. So, I did a curious thing. I sat like the statue of the Buddha in a photograph and, by closing my eyes and not following the thoughts – letting the mind rest, which is the beginning of meditation – it had a very profound effect. I found that all of my problems went away. When I started thinking, they came back. I realized that, if you could do that on lsd, you could do it in real life. By the late 1960s, I was encountering lots of people who had met the Tibetan lamas in India. I was seeing a path. So, in early 1971, I travelled to India. I went to Delhi and then up to Almora in the Himalayas, where Timothy Leary’s ex-wife, Nena von Schlebrügge, and Bob Thurman were living. Bob said to me: ‘We’re going to see the Dalai Lama tomorrow, would you like to join us?’ This was on the other side of India. I said, yes. They had a son, Ganden, who was four years old and a baby daughter who was six months old. The baby was Uma Thurman. So, we took this long drive and saw the Dalai Lama for a week. I came to see him every day with Nena, Uma and Ganden. Uma was always crying, so Nena would take her outside and I’d be left alone in a room with the Dalai Lama and Bob, who talked in Tibetan, while Bob received teachings. It was totally wonderful being with the Dalai Lama. I went back to Almora, then to Sarnath and Benares. Three months later, I went to Darjeeling, where I met H.H. Dudjom Rinpoche, the head of the Nyingma tradition, who became my teacher. I happened on a fortuitous moment when a dozen of the greatest Tibetan lamas were living in Darjeeling, having come as refugees in 1959. My five years – from 1971 to 1975 – were a golden age of great blessings and teachings. Some died and all the other lamas had to move away because of a Maoist insurgency in West Bengal, which made Darjeeling dangerous. They went to Kathmandu, before coming to New York.

AH When you were studying Nyingma and meditating, did you see any analogy between the practice of sitting and letting thoughts arise and pass, and your earlier use of found material in your poetry: being open to contingency in any kind of practice, whether religious or artistic?

JG Maybe I intuitively understood chance. When you do Buddhist meditation, you’re training the mind. You watch thoughts arise, you see them, and you don’t follow them. Not following the thoughts, they vanish, doing vipassana, meditation practice. Meditation is good for all artists but particularly for poets and writers. You build a muscle where you’re able to see the thoughts arising and work with that. So, when you’re not meditating and thoughts come, you have the ability to see them more clearly, and grab them.

AH How did you reconcile Buddhism with Western avant-garde traditions?

JG Poets have an enlightened Buddha nature. Burroughs is an interesting example, he was not a Buddhist, yet his work was made with an intuitive understanding of the empty nature of the mind – his whole life was about that. He originally came to it through drugs and being a junkie, and trying to realize the nature emptiness permeates his work. So, he loved Buddhists like me and Ginsberg. He got the inside scoop. He lived downstairs here in ‘the Bunker’. When I came home from retreats, he would ask me endless questions. But he’d say [imitates Burroughs]: ‘Don’t call me a Buddhist. Don’t call me a Beat poet. Don’t call me anything.’

By the late 1990s, we knew William was going to die so, in our own subtle ways, Ginsberg and I would give him meditation instruction here in New York or when we visited him in Kansas. About a year before he died, I brought it up, and Burroughs said to me: ‘John, I’m so tired of watching my mind.’ I’m sure our training was of some benefit to him when he died.

AH Can you tell me about your AIDS activism in the 1980s?

JG I saw it really early and did not quite believe it. In the beginning, it was called ‘the gay man’s disease’. When I thought about my life from ‘Pornographic Poem’ to being a part of the gay liberation movement – whatever that meant – it was a complete catastrophe. Everything I had aspired to was a failure. I decided I had to do something. In the 1960s and ’70s, when you were politically active, a lot of it was fundraising because people got busted and had endless lawyers’ bills. I had already spent ten years raising money for political causes, but I realized by 1982 that the only thing people with aids needed was money for their expenses, direct help. We already had Giorno Poetry Systems, a non-profit foundation, so inside of that I started the aids Treatment Project. The Giorno Poetry Systems LPs made a little money, so I and the other poets gave our royalties to the fund. I treated it as in the golden age of promiscuity; you made it with somebody you were attracted to, and you didn’t ask their last name. I reached out through a network of friends giving grants to people in trouble – in the early years, everyone was dying – and made it personal with a hug and affection. It went on for 20 years until half of the sick poets were 50 years old and had suffered a stroke or been diagnosed with cancer. I said to myself: I’m a poet, not a healthcare provider, and then it was over.

AH What do you think of poetry today?

JG The last 50 years – or even longer – has been the golden age of poetry, starting with that stupid thought about poetry being boring at the O’Hara reading. Poetry has certainly changed, but more people in our culture are refining language to its highest degree than ever before. Just the way people’s minds get trained by texting and the use of social media. All of this is being done by millions of people around the world, and it’s all poetry. Then you have rap and hip-hop and other popular forms. The only things that have died are modernism and lyrical poetry as formal concepts.

AH And you’re fine with that?

JG Well, the sonnet died: give me a break! It was put out of its misery. Also, if you want to write a sonnet, please do. Our culture is now creating many new poetic forms. Countless internet bloggers, read by countless people, write truly great examples of what we used to call prose poems. As extraordinary technologies change our DNA for the positive in generations to come, I can’t imagine what will happen. But you can’t kill poetry; it keeps coming.

John Giorno lives and works in New York, USA. He is the subject of ‘I ♥ John Giorno’, which was conceived as both a retrospective and an artwork by Ugo Rondinone, at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France, until 10 January. In 2015, Giorno had a solo exhibition, ‘God is Man Made’, at Almine Rech Gallery, Paris.