Who Owns What? Who Can Speak for Whom?

A survey of international writers, curators and artists in response to recent controversies surrounding appropriation

A survey of international writers, curators and artists in response to recent controversies surrounding appropriation

To investigate appropriation today means not only to examine the foundations of contemporary art but also to explore complex recent debates around the subject. With this in mind, the October issue of frieze includes a themed section with contributions from novelist Hari Kunzru, artist and writer Coco Fusco, theorist Diedrich Diederichsen, artist Renèe Green, musician and critic Vivian Goldman, poet Claudia Rankine and filmmaker Alix Lambert.

As a supplement to the printed section, which moves through recent controversies surrounding appropriations, the intertwined histories of music, sampling and influence, and the potential biases of artificial intelligence devices, frieze.com has invited a cross-section of international artists, curators and writers to respond, via statement, image, or film, to the questions:

When are acts of ‘appropriation’ warranted in art and culture, and when are they not? Who owns what, and who can speak for whom?

John Keene

Candice Breitz

Kenneth Goldsmith

Khalil Rabah

Sarah Schulman

Bárbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca

Victor Ehikhamenor

Monira Al Qadiri

Deborah Kass

Ho Tzu Nyen

Yoshua Okón

John Keene

John Keene is the author of the novel Annotations (New Directions) and the short fiction collection Counternarratives (New Directions), which received a 2016 American Book Award. In November 2016 he received a Lannan Literary Award in Fiction. He has also published a translation of Brazilian author Hilda Hilst’s novel Letters from a Seducer (Nightboat Books / A Bolha Editora), as well as translations of a wide variety of poetry and prose from Portuguese, French, and Spanish. A longtime member of the Dark Room Writers Collective and a graduate fellow of Cave Canem, he serves as chair of African American and African Studies and teaches English and creative writing at Rutgers University-Newark.

If cultural exchange is a profoundly human act and entails various kinds of borrowing, cultural appropriation might be viewed as theft, or body-snatching, figuratively and at times literally. The terms by which to understand and discuss cultural appropriation depend upon – require – acknowledgement of the specific and broader contexts, always shaped by and subject to larger historical, sociopolitical and economic forces and discourses, in which cultural appropriation has occurred and is unfolding. Even a cursory glimpse at local and global histories will show that unequal power relations, in the form of systems of domination and oppression like colonialism and imperialism, and via ideologies like racism, white supremacy and racial privilege, sexism, and misogyny, and so forth, mark and colour cultural interactions and the politics of representation and performance. When one dominant, privileged group of people has had the power to determine not only how they see another, subaltern or marginalized group, but how that subaltern or marginalized group – and the rest of the world – sees and reacts to itself, and when that dominant group has repeatedly taken the cultural production of those groups, renamed it and claimed it as its own, the question of cultural appropriation must be raised and addressed. Additionally, the dominant group's privilege of considering this theft as fine, receiving regular validation for doing so, and being so privileged and entitled as not to brook challenges or criticism about it, to the point of silencing or ignoring critics, also are hallmarks of cultural appropriation. Cultural borrowing and exchange are central to dynamism in art and life. But taking that goes in only one direction, that occurs with the presumption of privilege and entitlement, and without humility or self-questioning; that happens without respect for the group from which any cultural artifact or trace is being taken; and that is done without attribution or elision of the origins and sources of the cultural artifact, constitute cultural appropriation, especially in the ways it is now regularly and rightly being criticized. The zombie idea of ‘political correctness’ unfortunately can no longer provide cover.

Candice Breitz

Candice Breitz is an artist based in Berlin. She represented South Africa at the 2017 Venice Biennale.

What kind of stories are we willing to hear? What kind of stories move us? Why is it that the same audiences that are driven to tears by fictional blockbusters, remain affectless in the face of actual human suffering?

Kenneth Goldsmith

Kenneth Goldsmith is a poet who lives in New York City. His latest book, Wasting Time on the Internet (2016), is published by Harper Perennial.

In recent conversations surrounding cultural appropriation, one big fact often seems ignored: that the derivation, distribution, circulation, and reception of cultural artefacts takes place on the internet – a giant copying machine. The web displaces specific contexts and annuls singularly verifiable provenances in order to create infinite versions, infinite meanings, and infinite sites of reception. On the web nothing is stable. On the web you're always right – and you're always wrong. The ethics of the network are aethical. The logic of the network is illogic. On the network your feelings aren't facts – they're artefacts. Attempts to glue the web back into a cohesive entity rebuke the structure of the network, which is shattered and distributed. You can't put the genie back in the bottle. Trying to police and enforce the way images are used is like trying to patrol the universe. Free-floating artefacts have their own agency, which are dictated by the architecture of the network, not by your attempts to wrestle them into submission. Critics of appropriation who wilfully ignore and underplay the digital remind me of those same legions who unironically complain about corporate culture on Facebook. Stay angry – your outrage is monetizable. Legislating responsibility in a digital environment assumes that you're in control. You're not.

Khalil Rabah

Khalil Rabah is an artist who lives and works in Ramallah, Palestine. Recently, he has been the subject of solo exhibitions at Casa Árabe, Madrid, Spain, and Kunsthaus Hamburg, Germany, and has been included in the Sharjah Biennial (2017); ‘After the Fact. Propaganda in the 21st Century’, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich (2017); and the Marrakech Biennale, Morocco (2016). Rabah is the co-founder of Al Ma'mal Foundation for Contemporary Art, Jerusalem, and the Art School Palestine, London, and is the Director of the Riwaq Biennial, Palestine.

Sarah Schulman

Sarah Schulman is a novelist, playwright, screenwriter, nonfiction writer, AIDS historian, journalist and active participant citizen, based in New York. She is the Co-Founder of MIX: NY LGBT Experimental Film and Video Festival, co-director of ACT UP Oral History Project, and the US Co-odinator of the first LGBT Delegation to Palestine. Her latest book, Conflict Is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility and the Duty of Repair (2016) is published by Arsenal Pulp Press.

I teach at the College of Staten Island, in New York, a public open-admissions university where less than 30% of students graduate in eight years. Tuition is USD$5,800 a year and 80% of students receive financial aid. A recent report in the New York Times showed that 50% of the hundreds of thousands of students on the 23 campuses of CUNY (City University of New York, to which CSI belongs) live in households with income of USD$30,000 a year or less. I usually have students from ten to 15 different nationalities in each class, and most of my non-immigrant students are Italian or Irish American working-class kids, often the children of police officers, sanitation workers and fire fighters. 20% of my students are Muslim. I find that national trends among private school students are rarely reflected in our classrooms. A casual survey of my colleagues revealed that none of them have ever been asked for a trigger warning. Instead of using the word ‘violence’ to mean conflict, discomfort, or anger, many of my students live with a great deal of physical violence in their lives, and are not sure if this is a problem. Casual violence, rape and parental drug use are common themes in my students’ creative writing – not as exposés, but as un-self-conscious representations of daily life.

I have taught Fiction Writing at CSI for 19 years and I find that my greatest challenge as a teacher is to find a way to help students write about their own lives. Usually the white American kids want to write fantasy or speculative fiction spun off of existing series, where the characters and tropes are pre-determined from television, Manga or cult novels. I let them do this once, to get it out of their systems, and then forbid it on the basis that the work is ‘derivative’ and not innovative. I suggest they instead approach scenarios from their own lives. Most of the immigrant students hand in stories with white protagonists. Some of these are set in a fictitious ‘America’ that they have never visited, since most know only New York and their home country. This America is not a ravaged landscape of Wal-Mart and crystal meth, but is instead a sterile bucolic homespun environment. It takes a lot of conversation, many exercises and sometimes a demanding insistence to get my students to write about their own worlds. They claim that it’s ‘boring’, they are embarrassed by their difference, poverty, they feel disloyal by describing their family members.

What my students are experiencing is disconnection from their own lives because these lives are almost never represented accurately on TV or in the movies. Most of my students’ lives are not part of mainstream cultural representation. They simply have no opportunity to see themselves. If they ever do appear it is in distortions as broad as helpful hero cops, thieves, drug addicts, terrorists or shop keepers. In order to feel like ‘real writers’ or ‘real Americans’ they take on the dominant white protagonist, and relegate the stories of their communities and collective experiences to the trash. The undoing of this trap is one of the purposes of our course. The distorted appropriation by a biased entertainment industry, renders my students’ lives marginal and has lasting effects on their silence about their own experiences.

Bárbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca

Bárbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca are artists based in Recife, Brazil. They have worked collaboratively since 2012. Their work has been included in group exhibitions at: Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Brazil; Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; the 32nd São Paulo Biennial (all 2016); Skulptur Projekte Münster, Germany; the 25th Panorama da Arte Brasileira at the Museu de Arte Moderna, São Paulo; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Detroit, USA; and Vila do Conde, Porto, Portugal (all 2017).

Victor Ehikhamenor

Victor Ehikhamenor is an artist, photographer and writer born in Nigeria, who works between Lagos, Nigeria and Maryland, USA. His works are influenced by the duality of African traditional religion and the interception of Western beliefs, memories and nostalgia. Ehikhamenor’s work has been shown in both solo and group exhibitions at venues around the world, notably the German pavilion as part of the 56th Venice Biennale, curated by Okwui Enwezor in 2015 – he is currently one of three Nigerian artists showing at the 57th Venice Biennale, 2017. He is a recipient of the Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship in Bellagio, Italy.

Who owns what, how is it owned, who is appropriating what, and within what context? One can't use the same hammer on every nail, lest we overlook the fact that culture influences culture and people inspire people. However, we should agree that there is never a time when art/cultural ‘appropriation’ is warranted; when there is a power/institutional imbalance between the owner of a certain culture and those encroaching on it for financial, or other, gains.

The masks produced by classic African artists come to mind. When you look at the contentious history between Nigeria and Britain, for instance, and the punitive expedition of 1897 carried out by British colonial officers in Benin Kingdom, one gets a bit queasy. The masks from Benin or Ife in Nigeria, many of which were seized by the British forces, are distinctive in their craftsmanship – whether bronze, terra cotta, or wood, they are stylistically unmistakable. Therefore, there can be no questions posed as to who owns what. When modern European artists ‘reference’ these African works, replicating their forms and aesthetics and making very few alterations, the unlit line of inspiration and appropriation is crossed. A recent example of this came courtesy of Damien Hirst and his work Golden heads (Female), 2017, included in his exhibition ‘Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable’ at Palazzo Grassi, Venice.

Such a crude action will like many before him, of course, inhibit future legitimate acts of cultural exchange. My people have a saying: a woman whose child is bitten to death by a snake will not allow a wall gecko to come near another of her children.

Monira Al Qadiri

Monira Al Qadiri is a Kuwaiti artist born in Senegal and educated in Japan. In 2010, she received a PhD in inter-media art from Tokyo University of the Arts, where her research was focused on the aesthetics of sadness in the Middle East stemming from poetry, music, art and religious practices. Her work explores unconventional gender identities, petrocultures and their possible futures, as well as the legacies of corruption. She is part of the artist collective GCC.

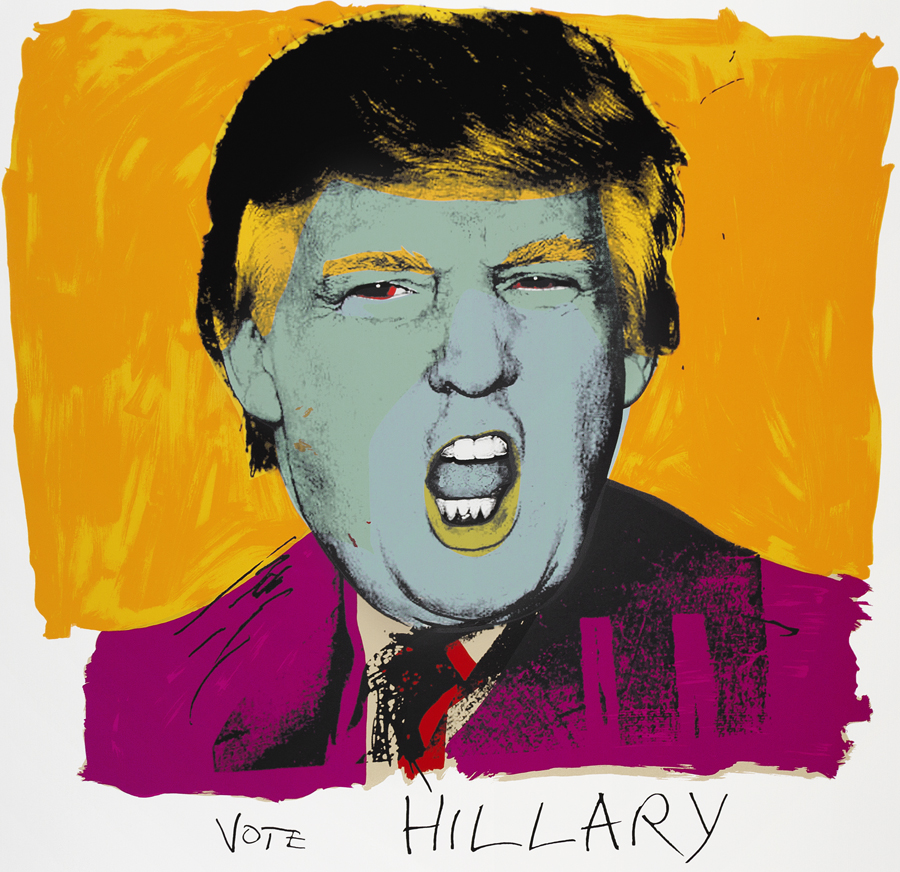

Deborah Kass

Deborah Kass is an artist who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Her work is held in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Museum of Modern Art, The Whitney Museum of Art, The Jewish Museum, and the Smithsonian Institute, amongst others. Kass’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, and has been included in the Venice Biennale and the Istanbul Biennale. In 2012, The Andy Warhol Museum staged ‘Deborah Kass, Before and Happily Ever After, Mid-Career Retrospective’. Kass was inducted into the New York Foundation for the Arts Hall of Fame in 2014; presented with the Passionate Artist Award by the Neuberger Museum in 2016; and was the Cultural Honoree at the Jewish Museum in 2017.

As an artist and American citizen I believe in the bedrock principle of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. Free speech is protected under the law.

The question is: In the age of Trump, what are the consequences of inappropriate, insensitive or offensive speech? It is striking how the repercussions of questionable speech vary wildly depending on who is being spoken about, who is the audience and, most importantly, who is doing the speaking.

Just like our new administration, the art market continues to ruthlessly marginalize and devalue the voices of specific groups of citizens (women, LGBTQA, indigenous Americans, and people of colour) to ensure the financial supremacy of the very few – 99.5% of whom happen to be white men. In my work I use appropriation to interrogate the mechanisms of power and value in the asset class of post-war art and its official record, art history.

When men paint women in overtly sexist ways, as they have for centuries, there is barely a whisper of protest. When white men culturally appropriate from less powerful classes, they face little pushback. Sometimes they do, but then they apologize and are congratulated with institutional prizes as a result. The question of free speech, cultural appropriation and representation remains one of privilege and power, which still reside firmly in the hands of white men.

Ho Tzu Nyen

Ho Tzu Nyen is an artist who lives and works in Singapore. His film, video and theatrical works often appropriate the structures of epic myths to invoke their grandeur as well as to reveal these narratives as fiction- and reality-machines. He has had solo presentations at The Guggenheim Bilbao (2015), DAAD Galerie (2015), Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2012), Artspace, Sydney (2011) and represented Singapore at the 54th Venice Biennale (2011). He has recently participated in exhibitions at the Lofoten International Arts Festival, Norway; National Arts Center Tokyo, Japan; Cultural Center Belgrade, Serbia; Center for Contemporary Art Singapore and Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin.

The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia is a platform for absorbing online video materials which are annotated, then fed into an algorithmic editing system that endlessly composes new combinations of audio-visual materials online, according to the 26 terms of the dictionary. Each term is a concept, a motif, or a biography. Together they are threads weaving together a torn and tattered tapestry of Southeast Asia, a region that has never been unified by language, religion, or political power.

In the Dictionary, the letter ‘Q’ is sometimes rendered as ‘Q for Quotation’, accompanied by the following text:

A quotation is a quaking thought

always vibrating

with the presence of another thought

Thoughts falling

on my head

like raindrops

Yoshua Okón

Yoshua Okón is an artist who lives and works in Mexico City, Mexico. He has had solo shows at ASAKUSA, Tokyo; Salò Island, UC Irvine, Irvine; Piovra, Kaufmann Repetto, Milan; Poulpe, Mor Charpentier, Paris; the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; and Städtische Kunsthalle, Munich. His work has also been included in group exhibition at: Manifesta 11, Zurich; Gwangju Biennale, Korea; MUAC, Mexico City; Musèe Cantonal des Beux-Arts, Lausanne; Palais des Beaux Arts, Brussels; Hayward Gallery, London; and New Museum, New York.

I think that questions like ‘who can speak for whom?’ and ‘who owns what?’ are not productive at all. They are, in fact, questions that often lead to censorship and, instead of solving the issues they try to resolve, end up making matters worse.

We live in a postcolonial, postmodern age in which we are more interconnected and interdependent than ever; we are all in the same boat and solutions need to be found collectively. If we want to address issues of exploitation, issues of plagiarism, issues of poverty and issues of racism, then we should address them for what they are, and in a direct way. Trying to establish who owns what cultural or racial heritage is to think in terms of racial or cultural purity, ridiculous notions that bring division and not unity. These kinds of questions are not only a waste of time; they also lead us down a very dangerous path that might inspire yet more violence and alienation.