Who is Sterling Ruby?

Grappling with the work of an artist who relishes multiple viewpoints, myriad materials and a slippery approach to meaning

Grappling with the work of an artist who relishes multiple viewpoints, myriad materials and a slippery approach to meaning

‘And he invents spaces, of which he is the convulsive possession.’

Roger Caillois

Landscape Annihilates Consciousness

On screen: a blob of viscous matter is gathered on a palette, and then smeared against a blank field. The image is accompanied by a soft, soothing, cajoling whisper, a voice, and the sound of repetitive movement: ‘I’m gonna just tap. Just gonna tap, very lightly. I don’t want to destroy. I want to diffuse. Now very lightly, lift it upward. See now, it softens it, pushes everything back. You can continue to do this ‘til it absolutely disappears on you, if you want to. You can soften it to any degree of brightness or darkness that you want in your world.’ A picture begins to emerge from planes and volumes: a snow-covered mountain landscape, the result of this tapping, softening, and diffusing. And where the painting is elaborated progressively, the voice loops back. In repetition, the murmured instructions come to seem like a mantra of sorts. Under their spell, the painter’s steady articulation of a conventional landscape comes to be more and more ambiguous.

In its 19th-century heyday, landscape painting put forward a human confrontation with the matter and appearance of the natural world. Sterling Ruby’s video, Landscape Annihilates Consciousness (2002), shows the practice as now deformed and inverted, determined instead to idealize and ‘diffuse’ this material world, ‘’til it absolutely disappears on you.’ Conventional landscape painting is figured here as the neutralization of world and mind. Reduced to its pure semiotics, painterly modulation becomes transcendentalist death wish. The last thing the painter renders is a house: flat geometry and broadcast television now produces the picture of a rustic pre-modern cabin – a nostalgic and ideological fantasy. Sovereignty is established, and totality realized. This painted world belongs to the artist, and – through the apparatus of televisual transmission, in the form of Bob Ross’ show The Joy of Painting – his world is to be yours. And yet the video dramatizes another turn as well: in his looping narration, the painter-fantasist is stuck, inertial, repeating himself. He is prey to his own creation. Annihilated and consumed by landscape, he is the one who fades into the background.

Legendary Psychasthenic

Who is Sterling Ruby in this arrangement? Which position does he inhabit? Is he the annihilated painter, or the mesmerized viewer? Is he the absent presenter of an altered artifact – its conduit or amplifier – or does he observe with us? In this video, and elsewhere, Ruby converges with each of these identities in turn, in a universe of effects without causes. Form is infinite, and dispossesses everyone equally: producer and consumer, image-maker and the one who looks. This troubled shifting of positions casts the artist one moment as producer of a heterogeneous range of conventionalized objects and styles – abstract paintings, Dada-lite collages, Minimalist art, Situationist posters, graffiti, ceramic earthenware, and so on – and the next as the outraged and dispossessed consumer of the generic signs he has produced; a third moment might find him ironizing this hysterical reaction, lacerating its private aspirations to totality; and so on.

‘Sterling Ruby’, then, is an unstable sign for a set of convergences, enactments, and circumscriptions – indeed, in its blank preciousness his name reads like a pseudonym, as if he were a fictional character. This conclusion is affirmed elsewhere: ‘The character at work,’ wrote Ed Schad in a review, ‘is not Ruby specifically, but a person who makes art created by Ruby.’1 ‘I have always thought of Sterling as a serial killer Joseph Beuys,’ Sarah Conaway declared in the third section of Ruby’s 2005 video Transient Trilogy. ‘Each pocket of work came from a different viewpoint’, Ruby told Holly Myers in 2006. Yet they share a ‘lineage’, he continues: ‘a dichotomy of repression and expression’.

Abyss of Negative Utopias

This ‘Ruby’ has been prolific since his first solo exhibitions, which began in 2003, while he was a student at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena; a survey will include ceramics and sculpture, posters and collages, and finish up with his synthetic exhibition-forms and video works.

His work deals with the production of space, including abstracted ceramic biomorphs, polyurethane stalagmites, and stained or defaced ‘Minimalist’ objects. His 2008 exhibition ‘Kiln Works’ at Metro Pictures is emblematic of this approach: convoluted and asculptural objects reproduce the organizational logic of microcellular organisms (Clover Dear, Blackout Romeo, all works in the exhibition 2008), simple containers or tools (Mortar and Pestle, Bread Basket), and mutant artifacts (Head Artist / Archaeology). Applied with expressionistic fervour, liquid rivulets of drizzled glaze are fired into unlikely, grotesque anti-forms – flayed turkeys, uterine dissections – that shade unexpectedly into ostentatious ornaments (Pyrite Fourchette) or weird reliquaries (resonating with Paul Thek’s and Lynda Benglis’ work, among others). These objects nevertheless relate to human size, embracing their domestic status as things for us, sometimes with comic literalness: Bread Basket is no bigger than its namesake.

Installed for ‘Killing the Recondite’ (Metro Pictures, 2007) or ‘Stray Alchemists’ (Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, 2008), Ruby’s ‘stalactites’ embrace instead an architectural and geological logic of phallic verticality, somewhat effaced by the alien fragility of the polyurethane strands from which they are composed. Like the ceramic artifacts, these are borne up by support structures marked as objects in their own right: wooden gallows, beam structures, minimalist cubes, plinths, and ethnographic or consumerist display platforms. These geometrical structures are evocative of public sculpture and the relative anarchy it can provoke: works like Inscribed Monolith (EPA-Alabaster) (2006) incorporate scrawled graffiti, fingerprints, and aggressive inscriptions on their surface. But they can also act out that version of minimalism which instates an oppressive ‘inclusiveness’.2 For example, Superoverpass, (Foxy Production, 2007), a minimalist arch which compresses the space of the gallery and looms above the viewer, or the various Inscribed Plinths from ‘SUPERMAX 2008’, presented by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, which confront and structure the physical behaviour of their audience. They enact an oppressive minimalism to destroy it – to exacerbate and attack Minimalism’s perverse logic of power, its negative Utopia; even so, they are subject to the contradictory logic of iconoclasm, which reifies and glorifies the power it aims to defile. Defaced, shat upon, decapitated – titled Headless Dick / Deth Till (2008), one work presented an erect and bloodied formica shaft – and forced to bear the written language its pristine surfaces meant to forestall, 1960s Minimalist sculpture remains ineradicably and inevitably at the centre of the story. So too does the established critique of minimalist form as brutal and domineering, famously articulated by art historian Anna Chave in her 1990 essay ‘Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power,’ come to seem, in Ruby’s new context, reciprocally grotesque – paradoxically in love with the movement it means to insult.3

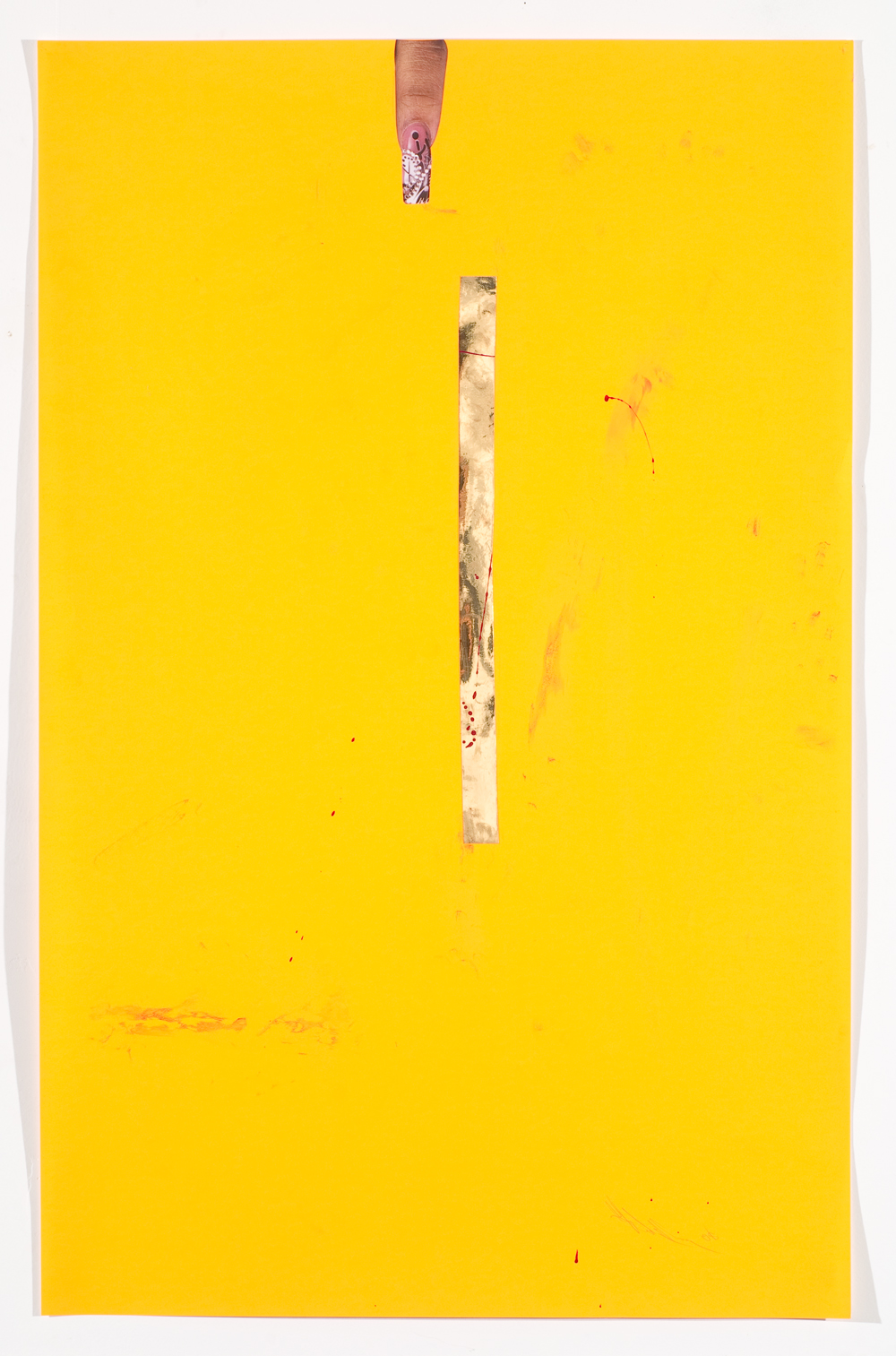

Gesamtzerstörwerk

Paintings, posters and digitized collages map out a second zone of heterogeneous activity, pictorial in nature: breathtakingly lurid paintings, bright, sharply-defined acrylic spatters over blurred, neon topographical maps (such as Spectrum Ripper, 2008); fungal smears of dye captured in thick blocks of translucent urethane (Absolute Contempt for Total Serenity / DB Deth, 2008); bubblegum zones of flesh and mint and orange, stained with nail polish and framing magazine clippings of military camouflage and a depiction of a dressed wound (American Soldier – Digital Camouflage Composition, 2007). Collages notice strange patterns in the detritus of culture, and assemble them for our view – for example cross-breeding high Modernist abstraction with LA gangs’ colour fixation in FEMALE GANG HANDS (2007). Or they barrel off with giddy takes on postmodern body culture that decry formal domination (‘Long Live the Amorphous Law’ reads a graffiti slogan scrawled across Anti-Print Poster 3, 2007) and locate allegories of metamorphic possibility. These include the male-to-female transsexual effacing her phallus who appears in Trans Compositional (Crimped Red Hair, Cream Satin Dress) (2006), alongside gestural droplets of red nail polish that are themselves ‘reoriented’ from horizontal to vertical; and the bodybuilder whose physique mimics an erect penis in ‘Physicalism – The Recombine series’, (2006), as their clenched bodies are paired with – or have their heads replaced by – biomorphic candles.

To describe the works in this way, however, is to present them problematically severed from their system of objects. In their synthetic forms – exhibitions, video – Ruby’s works achieve a more programmatic scenography. The installation for ‘Stray Alchemists’ is a blasted psychedelic bunker; ‘SUPERMAX 2008’ presents the spires of a living organic city emerging from the inert remains of an imperial, minimalist urbanism. Paintings and actions are related to one another allegorically and semi-autonomously; they become accreted scenes and atomized props in a larger Gesamtzerstörwerk (a ‘total work of destruction,’ as historian Hanne Bergius once described the cumulated assemblage of Johannes Baader’s The Great Plasto-Dio-Dada-Drama, 1920).4 From this allegorical terrain of exhibition we perceive both Ruby’s meaning in fragments, and a traumatized and hysterical ‘Ruby.’

‘… ciphers of an infinite authority …’

Perhaps this ‘Ruby’ will assassinate or replace the artist who produced him. In Transient Trilogy he seems intent on erasing his twin from the story, at least judging by the quote from an essay by Roger Caillois worked into the video’s script as a voice-off: ‘If an artist is invested with what he does, then there is little possibility of disassociating the maker from the work. When work is specifically about the artist, or if the work is dependent on what the artist-figure is occupied with, then the maker can have no real distance from the work. The artist and the work are unified as a hermetic structure and isolated from outside influence.’ Alternately this artist is simply self-similar: ‘… not similar to something, but just similar.’5

Yet the ‘Ruby’ enacted by the work is hardly so hermetic or isolated; rather, pre-existing sources, references and theories pervade his work, where they are brought into a contradictory and mutually embarrassing constellation. Critical theory ruptures artistic practice, even as its aphoristic obscurity is lampooned. Every work comes readymade with theoretical armature, self-annihilations, didactic instructions, blasé refutations, rabid slogans and more. This can leave an attentive viewer confounded – wondering if theirs is just another paranoid inscription onto forms full of evident energy, but still mysterious or essentially arbitrary. Ruby is clearly aware of what Henri Lefebvre described as ‘the vanity of a critical theory which works only at the level of words and ideas (i.e. at the ideological level)’.6 Yet his practice leaves both theorists and artists in place, as ciphers of an infinite authority that might be resented but never overcome.

Dark Space

The final moments of Transient Trilogy: a camera scans the graffiti-covered terrain of a ‘natural’ reserve (gravel paths are in view, and cars just out of sight) and discovers a character, played by Ruby, trousers around his knees and head tucked into his arms. This is the homeless ‘transient’ of the work’s title, who ‘makes art by marking and decorating the environment’ – though it is inevitably erased by time and entropy. So too is this character caught in a troubled flux of sexual identity: hermaphroditic and sterile, the trans-figure is discovered in a moment of doomed and autoerotic sexual congress.

Figurations of this solitary, ‘fucked’ subject appear most clearly in Ruby’s video works; he ‘invents spaces of which he is “the convulsive possession.”’ Indeed this line is quoted in Dihedral (2006), which combines a voice-over reading a Caillois quote (again from the same essay) to a film of different dye-colors falling into a clear medium, a live-action Morris Louis painting. The ‘dihedral of representation’, for Caillois, stands for that context of perception wherein ‘the living creature, the organism, is no longer the origin of coordinates, but one point among others; it is dispossessed of its privilege and literally no longer knows where to place itself.’7 This demotion is presented, in the videos, alternately as terrifying – space becomes a ‘devouring force’, the subject merely a ‘dark space where things cannot be put’ – and perversely comforting: no longer forced by abstract form to identify himself, this subject can be one amorphous shape among others in a dedifferentiated universe.

This dream, however, is impossible to grasp – abstract space keeps intervening. The video works put forward several versions of this isolated character, dispossessed by space: the hiker, followed by the camera as if by a stalker, walking through a spectacular landscape transformed by the eye’s prerogatives, and perilously close to the abyss (Hiker, 2003); the vampiric office-worker who, bearing a camper’s rucksack, craves the comforting compression of a bathroom stall, sleeping bag or heating duct (Agoraphobic, 2001); the primitive-convulsive characters acted out by Ruby in Temper Tantrum / Intimate Death Magician (2003) or Found Cushion Act (2005).

In Transient Trilogy the character marks his presence in ritual fashion: cultish constellations of talismanic objects, spatters of nail polish. These efforts are not built to last, fading soon into indistinction. Stumbling into the woods, over a thick loam of leathery animal corpses and condom wrappers, the transient soon merges with the bushes. ‘Transient’ is not put forward as a social category, but as a state in which all life and form must inevitably exist: between life and death, male and female, form and formlessness. Not content to let this melancholic allegory stand, Ruby immediately reappears in a new role: an asshole director, whose ridiculous stage direction and squabbling with his intractable actor comically annihilates the sombre narrative that precedes it: ‘Listen! Think of Hamlet! The character who could not make up his mind.’

The Ruby of 2005 dramatized and ironized this punctured subject – an artist ‘afraid of yet obsessed with what went before and neurotically pursuing [his] own symptoms.’8 ‘SUPERMAX 2008’, on the other hand, puts forward the artist as the paradoxically exuberant governor of a rotting carceral order (the title refers to specialized ‘control-unit’ prisons). Geometrical abstraction is present still – in the form of stained and defaced plinths and grids – but these seem now to undergird an alien-geological order that stretches to the ceiling. The subject of this sci-fi scene remains troubled: permeated by a dark space that ‘touches the individual directly, envelops him, penetrates him, and even passes through him,’ he inscribes on the framework of Headless Dick / TSOVM (2008), and: ‘the past has cheated me/the present torments me’. Partly obscured, the third phrase reads: ‘the future … me’. The erased word is ‘terrifies’. Such negations are all the hope we get, in Ruby’s work. But perhaps they’re enough to live on.

1 Ed Schad, ‘Sterling Ruby: Supermax 2008’, Art Review, September 2008, p. 145

2 ‘Inclusiveness’ is Michael Fried’s term for a situation, precipitated by a ‘theatrical’ Minimalism, where ‘there is nothing within [the beholder’s] field of vision – nothing that he takes note of in any way – that, as it were, declares its irrelevance to the situation, and therefore to the experience, in question.’ Michael Fried, ‘Art and Objecthood,’ Gregory Battcock, ed. Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology, New York, E.P. Dutton & Co 1968, p. 127

3 Anna C. Chave, ‘Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power,’ Arts 64, January 1990, pp. 44–63

4 Brigid Doherty, ‘Berlin’, in Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, Paris (exh. cat.), Washington D.C., The National Gallery of Art 2006, p.97

5 Roger Caillois, ‘Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia,’ October 31, Winter 1984, p. 30

6 Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith, Oxford, Blackwell Publishers, 1991, p. 60

7 Ibid, Caillois, p. 28

8 Sterling Ruby, ‘A Brief Rebuttal to Michael Workman’, New City Chicago, 7 February, 2005, www.newcitychicago.com/chicago/4075.html